(I’ve been reading the stories that got both Hugo and Nebula nominations. To see all the posts in the series, check the “Joint SFF Nominations” tag.)

For the past few years there’s been a big overlap between the Hugo and Nebula shortlists. Generally we’ve had half a dozen or more stories to cover. For whatever reason, in 1972 fans and writers couldn’t agree.[1] There are only three stories to cover this time—maybe two, or two and a half, depending on how you look at it. (I’ll explain in a moment.) We’re taking a well-deserved break in:

1972

In 1972, the novels nominated for both a Hugo and Nebula were Robert Silverberg’s A Time of Changes and Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Lathe of Heaven. A Time of Changes won a Nebula. (The Hugo went to Philip Jose Farmer’s To Your Scattered Bodies Go.)

Only three shorter works were double-nominated this year:

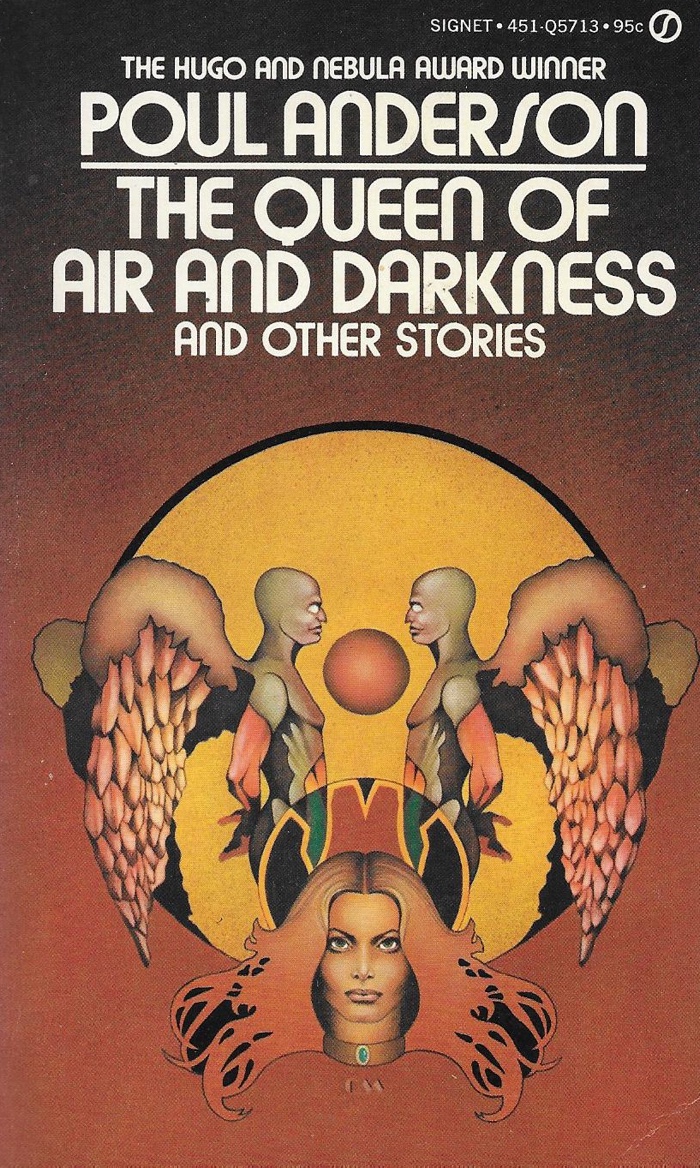

- Poul Anderson, “The Queen of Air and Darkness” (Won the Nebula for Best Novelette and Hugo for Best Novella): A suspiciously Holmesian consulting detective matches wits with a suspiciously alien Faerie Queen.

- Arthur C. Clarke, “A Meeting with Medusa”: An astronaut explores Jupiter in a space blimp and encounters an alien.

- Gardner Dozois, “A Special Kind of Morning”: A soldier fighting a more powerful enemy on an alien planet has a moral crisis.

Click through to the shortlists and you’ll notice “A Meeting With Medusa” doesn’t appear in the Nebula list. The eligibility windows for Hugo and Nebula nominations haven’t always overlapped perfectly. Sometimes a story’s Hugo nomination will come in one year, and the Nebula nomination in the next. So “A Meeting With Medusa” was nominated for a Hugo this year and a Nebula in 1973. (It won the Nebula.) This will come up again in other years.

My usual approach in this series is to look for shared themes between the stories, but the fewer stories you have the harder that gets. These three don’t have much in common. The good news is that although 1972’s stories aren’t as brilliant as 1971’s they continue to be not actually cringeworthy.

The Queen of Air and Darkness

Ever since Arthur Conan Doyle created Sherlock Holmes there’s been a bustling trade in knockoffs, the consulting detective equivalent of the merchandise sold on Amazon by manufacturers with names like MOOBEX and FLEZPIP. At first people got around copyright by creating bootleg Holmeses like Solar Pons and Sexton Blake. Or other detective followed the Holmes model without thinking about it: Agatha Christie saddled Poirot with a boring sidekick named Hastings until it finally dawned on her she didn’t need to. Now that he’s in the public domain Holmes has been everything from a cyborg to an angel to, more ridiculously, a high-functioning sociopath.

Poul Anderson’s “The Queen of Air and Darkness” stars a detective named Eric Sherrinford who lounges around his messy apartment smoking a pipe and claims “descent from one of the first private inquiry agents on record, back on Earth before spaceflight.” I did not find this encouraging. I like Sherlock Holmes. I like detectives who are not Sherlock Holmes. I have no interest whatsoever in Sort of Sherlock Holmes, But Not Really. These stories feel like shortcuts for writers running low on ideas. They invariably devolve into exercises in fannish reference-spotting. (“Okay (sigh), that’s from ‘The Hound of the Baskervilles.’ And that’s ‘The Speckled Band.’ I get it, already.”)

This story won me over, though, because Holmes is serving a thematic, metafictional purpose. “The Queen of Air and Darkness” is about archetypes. Humans screwed up when they came to the planet Roland: they’re not supposed to colonize inhabited planets, but this one has natives. Not that anyone realizes that yet. The powerfully telepathic Dwellers have chosen to hide and use the humans’ deeply embedded archetypes against them. “Historical, fictional, and mythical, such figures crystallize basic aspects of the human psyche, and when we meet them in our real experience, our reaction goes deeper than consciousness,” as Sherrinford puts it. The Dwellers hover around the countryside, playing the part of fairies. The old, creepy kind of fairies. They’re creating telepathic illusions, scaring the folksy space rustics, and kidnapping the occasional human child as a changeling. The idea here is that the Dwellers will turn the colonists away from modern society, controlling them through superstitions—reverence and fear of the Old Folk.

Sherrinford is hired to find a kidnapped kid. Which he does because, heck, he’s Sherlock Holmes. And that’s kind of a double-edged sword. Is being Extremely Sherlock Holmes healthy? “We live with our archetypes,” he asks, “but can we live in them?” The Dwellers’ plan is as much a trap for them as for the colonists. They’ve jacked straight into the human subconscious by using an archetype, but in the process they trapped themselves inside that archetype. While they’re fairies, they’re not themselves.

There’s this concept called a “thought-terminating cliché.” It’s something you say to cut off a discussion or line of thought. Keep saying now is not the time to talk about gun control and you never have to talk about gun control. Archetypes can be powerful, but follow them too closely and they work like thought-terminating clichés. That’s what the Dwellers want: don’t think about who might be out in the woods, it’s the Old Folk.

Which brings us back to those store-brand Sherlock Holmes stories I’m so unenthusiastic about. The writer who writes a Solar Pons story taps straight into the audience’s Holmes archetype and their warm and fuzzy memories of the Conan Doyle stories. The writer coasts on the mental association with a fun story about a smart, interesting detective without having to do the work to write a fun story, or create a smart, interesting detective, of their own. (This is also the most common failure mode for fan fiction.) To the extent these stories color within the Holmes lines, they’ve stunted themselves.

A Meeting With Medusa

“A Meeting With Medusa” is nothing like anybody’s idea of a well-structured short story. That’s the best thing about it—it’s refreshingly shambolic. It doesn’t force events into a neatly plotted arc. Arthur C. Clarke is not my favorite writer but I enjoyed this more than I expected; sometimes I want a story that doesn’t feel overtly story-shaped.

Clarke tells the story in three stages, all doing different things. The first part sketches out a decadent post-scarcity future in which people have augmented monkey butlers but are still vulnerable to blimp accidents. The second and longest part concerns Howard Falcon, blimp expert and crash survivor, and his expedition to Jupiter in a space blimp.

(I just like saying “blimp.” It’s an inherently funny word. Blimp.)

This middle stretch is exposition connected by a tissue of events. The prose is journalistic, studded with precise numbers, comparisons, and historical references—it reads like a National Geographic article from the future. The attraction here isn’t suspense. Falcon runs across potential dangers, but nothing feels fraught. It’s only barely about character. The sole point is to imagine what Jupiter might be like if it had life. It’s excited about speculation and exploration in a stereotypically science fictional way; we’re in pure sense-of-wonder territory. This is the kind of thing people imagine when you ask them to imagine “hard science fiction,” but more readable than the description implies.

The epilogue returns to earth and floats off in another direction. We’ve been told that after the accident Falcon was rebuilt like the Six Million Dollar Man, but it’s only now we learn how much: he’s a robot with hydraulic muscles and a human brain, gliding around on wheels. Like other SF around this time (i.e. “Masks,” the novel Man Plus, the Doctor Who serial “The Tenth Planet”) “A Meeting With Medusa” associates cybernetics with alienation, even suggesting enough artificial body parts make you a different form of life entirely. For Falcon humanity is “becoming more remote, the ties of kinship more tenuous.” Clarke takes this a step further. The future of human evolution is a recurring theme in his work, and for Clarke evolution is teleological. 2001 and Childhood’s End are the most obvious examples, but it’s here in “A Meeting With Medusa,” too. Falcon isn’t just different from the bulk of humanity, he’s better—an “ambassador” between “the creatures of carbon and the creatures of metal who must one day supersede them.” The story takes it for granted that humanity must inevitably be replaced by creatures who can fly space blimps.

Blimp!

A Special Kind of Morning

At this point we’re starting to see SFF directly influenced by the Vietnam war from the generation directly affected by it, which to some extent includes Gardner Dozois—as far as I can tell he was never in combat, but he spent a couple of years in the army as a journalist. Here he’s writing about an individualist guerilla war against a bigger and better-equipped collectivist enemy.

But “A Special Kind of Morning” isn’t a straight role-reversal cold war allegory. The individualism-vs.-collectivism conflict is complicated by the hierarchal Combine’s treatment of people as literal human resources. In the Combine your social caste determines even how conscious you get to be. The narrator grew up as barely-sentient living factory machinery—the perfect no-wage employee. Now he’s joined the Quaestors, the guerilla resistance, and he has to dehumanize the enemy in another sense to kill them. The Combine kill at a distance, impersonally, with the high-tech equivalent of bombs and drones. The Quaestors “killed people—not statistics and abstractions.” This is just the story of how the narrator realized he couldn’t do that anymore. Not a complicated plot, but told with a generous helping of symbols and metaphors (and notably better prose than the other stories, both plain and traditionally “transparent”).

Most of those metaphors are about time. The most devastating weapon of the war produces “discontinuities,” ripping the battlefield apart by sending bits forwards and backwards in time. The Quaestors look for old, forgotten ideas, like guerilla warfare, bullets, and personal combat, to fight the Combine. The story itself is a memory, a tale told by an old man about how he lost his leg. The planet where the story is set has an extreme day/night cycle, with different night plants and day plants going dormant and rising each dawn or dusk. A new morning literally changes the landscape.

Reduce it to the theme, and this story could be told about any war: it’s just a guy learning to stop dehumanizing people. Which is not a kind of story all SFF critics are on board with. Galaxy magazine used to run an ad juxtaposing bad western writing with a version search-and-replaced with science fiction jargon, sneering at the stories that were “merely a western transplanted to some alien and impossible planet” and declaring “YOU’LL NEVER FIND IT IN GALAXY!” Good SFF, the theory goes, deals with ideas that could only come up in SFF. So it might be interesting to ask what rhetorical moves this story makes by being science fiction instead of a realist story about, for instance, Vietnam.

First, there’s the distancing effect. Reality is big. It comes with baggage. Anything real—a city, a person, an event—is going to call up a whole host of associations in the readers’ minds. If a writer wants to make a point about, say, the cold war, they may decide they can make that point more sharply if they don’t have to deal with the United States or the Soviet Union, which the readers will view through their own preconceptions.

More importantly, fantasy is a license to exaggerate. Americans saw the effects of real combat on the news every night; an apocalyptic sci-fi weapon is a tool to convey the emotional devastation of war to a desensitized audience. And metaphors can be made literal, and explored at length; the Combine isn’t just dehumanizing, its citizens are replaceable, interchangeable machine parts.

So I’m not bothered by “space westerns.” And, as kind as I was to “A Meeting With Medusa,” serious hard science fiction is not my thing. The point of SFF is that it’s an opportunity to go wild; when SFF tries to be “realistic” it leaves its most powerful tool out of the box.

-

Some of the better-known short fiction with only one nomination included “Inconstant Moon” by Larry Niven and “Vaster Than Empires and More Slow” by Ursula K. Le Guin from the Hugo list; the Nebula list included “Good News from the Vatican” by Robert Silverberg, “The Missing Man” by Katherine MacLean, and, interestingly, “Being There” by Jerzy Kosinski. ↩

One thought on “The Venn Diagram of Science Fiction and Fantasy Awards: 1972”

Comments are closed.