(I’ve been reading the stories that got both Hugo and Nebula nominations. To see all the posts in the series, check the “Joint SFF Nominations” tag.)

I’m noticing a pattern. I loved the stories I read for 1966. I thought the stories of 1967 were lousy. I had criticisms of 1968, but at least half the stories were good. So is it time for a swing back in the other direction? Alas, yes. Get ready to feel weird and uncomfortable reading the science fiction of:

1969

(…or 1968, depending on how you look at it. As always, stories nominated in 1969 were published the year before.)

The novels that got both Hugo and Nebula nominations in 1969 were Rite of Passage by Alexi Panshin (the Nebula winner), Stand on Zanzibar by John Brunner (the Hugo winner), and Past Master by R. A. Lafferty. I’ve never read Rite of Passage but Stand on Zanzibar is a classic and Past Master is a gloriously weird, underrated novel reprinted in the Library of America’s recent sixties SF set. That set also includes Samuel R. Delany’s Nova, which got a Hugo nomination, and Joanna Russ’ Picnic on Paradise, a Nebula nominee. 1968 was a good year for novels.

It was not such a good year for short fiction, at least judging from the double nominated stories:

- Brian W. Aldiss, “Total Environment”: Harebrained United Nations scientists build a giant tower block in India and lock hundreds of people inside for 25 years because, as everyone knows, people locked in a crowded building for multiple generations will inevitably evolve ESP.

- Poul Anderson, “The Sharing of Flesh” (Won the Hugo for Best Novelette): Space anthropologists visit a lost human colony. Their security officer seeks revenge when a native kills and eats her husband.

- Terry Carr, “The Dance of the Changer and the Three”: A negotiator back from a world of incomprehensible aliens translates one of their folk tales.

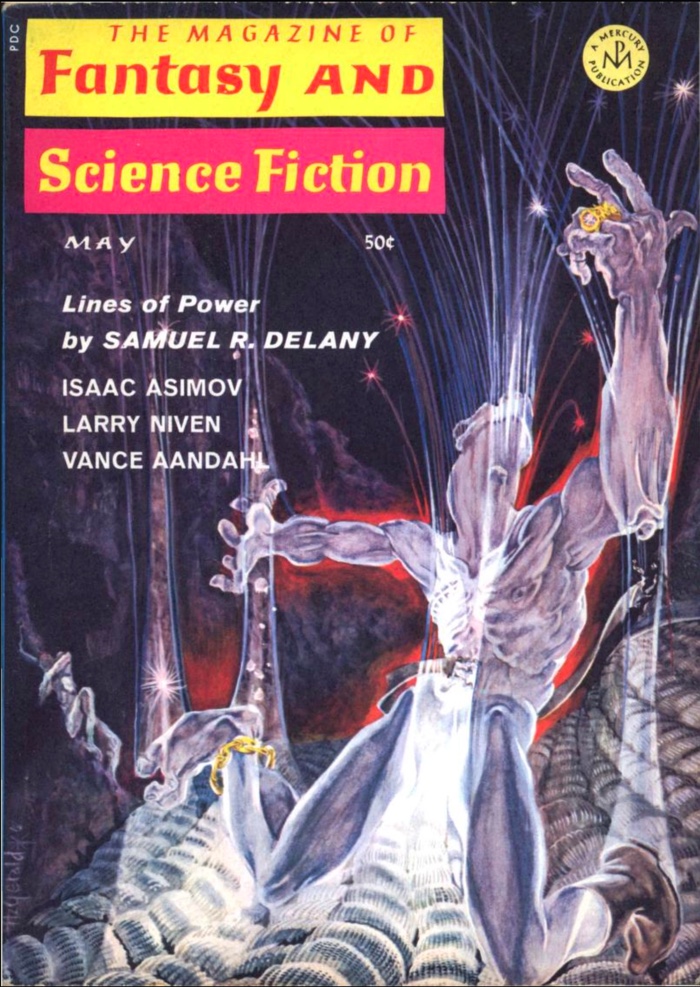

- Samuel R. Delany, “Lines of Power” (a.k.a. “We, in Some Strange Power’s Employ, Move on a Rigorous Line”): A utility crew tries to deliver electricity to one of the last unpowered places in North America. The locals aren’t enthused.

- Damon Knight, “Masks”: A man whose brain was installed in an artificial body finds it’s having a bigger effect on his psychology than anticipated.

- Anne McCaffrey, “Dragonrider” (Won the Nebula for Best Novella): The dragon riding people from last year’s “Weyr Search” are back. They fly around and argue a lot. Also, I guess they can time travel now?

- Dean McLaughlin, “Hawk Among the Sparrows”: An American pilot in a modern fighter jet time travels back to World War I, without even using a dragon.

- Robert Silverberg, “Nightwings” (Won the Hugo for Best Novella): In the far, far future, a man who’s spent his life watching for a long-prophesied alien invasion visits Rome.

- Richard Wilson, “Mother to the World” (Won the Nebula for Best Novelette): Everyone dies except one man and one woman, and everything just gets creepy and weird.

This is not as bad a slate as we had for 1967. There are high points. (I recommend “Lines of Power,” “Nightwings,” and “The Dance of the Changer and the Three.”) But brace yourselves, because the lows get super low.

Hawks

We may as well start anywhere, so we may as well start with “Hawk Among the Sparrows.” This is the lackluster tale of an American Air Force pilot who accidentally flies back to the First World War in his modern fighter jet. He’s weirdly blasé; it’s like he’s wandered into a Subway when he meant to go to Burger King. The pilot works out clever ways to leverage his jet against the Germans without modern fuel or weapons. As the story ends he expects the war will be over in a month. The prose is perfunctory, the plot predictable, the story as a whole as boring as it could possibly be, but I think I know why it appealed to a certain audience.

Analog published “Hawk Among the Sparrows” in 1968. By this point if not everyone accepted the Vietnam War was unwinnable they at least knew it wasn’t ending anytime soon. North Vietnam was fighting the greatest military in the world to a stalemate, and that was not how it was supposed to work, dammit. “Hawk Among the Sparrows” is a hawk’s fantasy of how the war should have happened, with an under-equipped enemy falling in record time. America would spend the next few decades looking for an easy war to soothe its bruised ego.

I said last time the nominated stories didn’t engage with the war, but by this point SFF feels less comfortable with colonialist violence. “Nightwings” shows an invasion from the invaded people’s perspective. In “Total Environment” high-handed scientists experiment on nonwhite people. In “The Dance of the Changer and the Three,” “Lines of Power,” and “The Sharing of Flesh” well-meaning people go into other cultures to trade with or “help” them and get in trouble when they won’t (or can’t) meet the locals on their own terms.

“The Sharing of Flesh” is an interesting case. Poul Anderson is a right-winger—you’ll recall he organized the pro-war petition in 1968. He believes in the Spaceman’s Burden: his crew has the ability and responsibility to help the benighted natives of Lokon. But even here there’s an unintentional ambivalence.

One strain of SFF is about contriving justifications for inhumanity. You must perform some cruelty, not because you’re evil but because, sadly, arbitrary and extremely unlikely circumstances have left you no choice. Like, normally smashing baby ducks with a crowbar is terrible, but what if these baby ducks were werewolves? Makes you think! The classic example is “The Cold Equations,” which invents an elaborately ludicrous rationale for its hero to throw a young woman out an airlock. The most popular modern version is the zombie apocalypse story, invariably an excuse to show its hero blowing the heads off an unreasoning mob with a shotgun.

“The Sharing of Flesh” is how this story looks from the wrong end. Evalyth is on an anthropological/humanitarian mission to the planet Lokon, where a guy named Moru kills her husband and makes off with his giblets. Investigating, she discovers a fact the expedition somehow managed to overlook: everyone on Lokon eats human organs as part of their coming-of-age ritual. (You know, one of those minor details.) Investigating further, she discovers the Lokonese have mutated and need hormones from those organs to mature. Moru fed Evalyth’s husband to his kids not because he’s an asshole but because, sadly, evolution has left him no choice. She gives up on revenge. It’s all very Dangerous Visions, except that book’s cannibal story (Sonya Dorman’s “Go, Go, Go, Said the Bird”) was actually good.

Anderson has, probably without realizing it, written his heroes as overconfident and clueless. If they failed to notice the ritual cannibalism practiced everywhere on Lokon—and I’d note they’re so incurious about the local practice of slavery they haven’t noticed the slaves are being eaten—how seriously are they taking the people they claim to want to help?

Power

The best story in this year’s batch is, again, by Samuel R. Delany: “We, in Some Strange Power’s Employ, Move on a Rigorous Line,” which The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction published as “Lines of Power” because they were cowards. This is a story about power, and power—electrical power and political power. The first image is the memory of an accidental electrocution. You have to be careful with power. You lose control, you get zapped.

What’s fascinating and baffling about SFF awards is the gap—heck, the yawning chasm—in quality between stories on the same shortlists. Many are the work of writers who think a story is just a description of things happening, with a pat moral or simple metaphor to add spice. And then you have the real writers, like Delany, whose fiction has depth. “Lines of Power” explores a thematic space and creates resonance by iterating through different definitions of power and evolving its imagery throughout the story.

In the future, the entire world has been hooked up to a high-tech electric grid providing too-cheap-to-meter power. The narrator, who goes by the nickname “Blacky,”[1] works on a mobile cable-laying machine the size of an office building. He’s just been promoted to “section-devil”—the line workers are “devils” and “demons”—and is learning the ropes from his fellow section-devil and former boss, Mabel.

The law says anywhere people are living has to be hooked up to the grid. The Global Power Commission found people living in a place that isn’t. This is High Haven, an estate on the Canadian border. The residents aren’t interested in going online. This is not (as would be most writers’ first thought) because they’re a low-tech community like the Amish. The Havenites are a biker gang descended from the Hell’s Angels. For the Angels to accept this devilish temptation would mean admitting the GPC has power over them.

Blacky negotiates with Roger, the head of the community. The last boss was a violent bully and Roger got the position by beating him up and driving him away. Roger can’t let Blacky win the argument because he can’t show weakness. To back down is to abdicate. Power based on strength is brittle. And, wielded without care or subtlety, it’s liable to turn on the user the way Roger turned it back on his predecessor. When Blacky tells us Mabel doesn’t like to waste power, it could mean more than one thing.

As for the rights and wrongs of unilaterally barging in to hook up High Haven, the story doesn’t come to any conclusions. Blacky wants to leave the Angels alone. Mabel is determined to install the lines because that’s what the law requires. When the Angels flee she stands down: with no one living at High Haven, it legally doesn’t have to be on the grid. Power needs conduits, constraints. Mabel keeps her power in check by sticking to the rulebook.

Getting or Not Getting It

Richard Nixon wouldn’t use the phrase “silent majority” until late in 1969, but as Rick Perlstein documents in his book Nixonland he had for some time sold his political career on dividing ordinary Americans from an imagined un-American liberal elite. Perlstein argues the late sixties were the origin of the United States’ current irreconcilable political cultures, incompatible not only in values but in epistemologies. The Vietnam war dragged on; the now-regular protests made no difference, and neither the doves or the hawks were changing anyone’s minds. Politics were getting violent. During the summer of 1967 a wave of antiracist protests across the United States escalated into riots when the police showed up, and in 1968 there were more riots at the Democratic Convention in Chicago. Meanwhile in the Hugos and Nebulas, our other big themes for 1969 are failures of understanding and irreconcilable differences. It feels like SFF is losing faith in people’s ability to understand each other.

Poul Anderson’s anthropologists miss basic facts about the Lokonese. The hero of “Total Environment” fears the people in the tower block and everyone outside are growing mutually incomprehensible. This is where “The Dance of the Changer and the Three” comes in. It’s good, and feels like Stanislaw Lem’s work. It is, first, a science-fictional folktale, a form Lem worked with in Mortal Engines and The Cyberiad. It also features really alien aliens. Like the planet Solaris and the aliens in Lem’s Eden and Fiasco, these are aliens we not only don’t, but can’t, understand.

The Loarra are energy beings. Every so often they “die” and re-coalesce as a new person. They’ve let a human expedition settle in to mine rare elements. (The Loarra are incorporeal, so I guess they’re not using them.) The narrator is the expedition’s public relations guy. He tells one of the Loarra’s oldest folktales, about three Loarra who create a new life form only to absorb it again. Then he tells us about the day the Loarra killed the miners, and afterward were as friendly as though nothing had happened, and couldn’t explain why. The reason was untranslatable.

Although there’s something just as alien closer to home. The survivors return to Earth and describe the situation to “Unicentral,” their computerized corporate overlord. They ask whether they should go back to Loarr. Unicentral can’t make up its mind. On the one hand there’s the risk to human lives. On the other, there’s money to be made. Like, a lot of money. The value of one is evenly balanced against the other. It’s possible the Loarra don’t understand what it means for humans to die. Unicentral doesn’t care.

Damon Knight’s “Masks” is about irreconcilable differences between human and machine. Jim is the first person to have his brain installed in an artificial body. His doctors worry he’s not adjusting—is he dreaming all right? Does he want a more expressive face? No, Jim’s problem is that, separated from his body, he’s lost every emotion but one. He’s grossed out. Organic life is leaky and squishy, and he can’t coexist with it. Knight’s writing is great, the ending has the force of a punch,[2] but “Masks” is thematically slight. There’s not much to it beyond Jim’s dissociation from humanity. It’s a familiar theme—not far off what Doctor Who had already done with the Cybermen. If you want more detail, Knight gives a close reading of his own story in the third edition of his book In Search of Wonder.

I said last time I wasn’t a fan of Robert Silverberg; I normally find his work fine but forgettable. But “Nightwings” is great—It feels colorful, like a Jack Vance story where not everyone is an asshole, and has real complexity. It’s about the gap between perception and reality, how we misunderstand what we see when we see it through our preconceptions. It’s thousands of years in the future and the narrator is a Watcher, a member of a guild watching the heavens for a long-anticipated alien invasion. He’s come to Rome (or “Roum”) for no particular reason. He suspects the invasion will never happen, that he’s wasted his life. The first time he sees the ships he dismisses them. They have to be his imagination.

The Watcher’s companions aren’t what they seem. He thinks the odd-looking Gormon is a human mutant, guildless and low-status in the eyes of society, though the Watcher respects him. But Gormon is something else entirely, and someone more powerful. Avluela is a Flier, a slight, winged human, and the Watcher thinks of her as a daughter. He describes her like she’s one of those old-fashioned science fictional ingénues who spend the whole story getting infantilized. But look past the Watcher’s narration and she’s making more of her own decisions than he realizes. (For one thing, he’s completely missed that she and Gormon are sleeping together.)

Avluela’s often the first person to ask important questions. When Gormon rattles off ancient Roman history she’s the one to ask “How are these things known?” Earth has forgotten its history. The guild of Rememberers have reconstructed parts, but there are still artifacts and ruins people see without understanding. When the aliens arrive the Watcher’s guild dissolves; their task is complete and there’s nothing left to Watch for. The Watcher leaves Rome intending to join the Rememberers. Depending on how you want to read the story, this could mean Earth no longer has a future to watch for. Or it may mean the Watcher can still learn to understand.

What the Hell, SFF?

I said 1968 was not a good year for short fiction. Here’s where I explain why. Only three stories are worse than “Hawk Among the Sparrows,” but they really bring the average down.

Anne McCaffrey’s “Dragonrider” is the sequel to last year’s “Weyr Search.” It picks up some time after the last story. I get the impression the events between might be included in the novel version. From what I gather F’Lar and Lessa’s dragons mated, and sort of mind-controlled F’Lar and Lessa into also mating, and now they’re dragon-shotgun-married and sleeping together even though they hate each other? F’Lar is constantly shaking Lessa, like Homer Simpson is always strangling Bart. Incredibly, this is not the creepiest sexual relationship we’ll see in this batch of stories.

Anyway, F’Lar and Lessa spend “Dragonrider” bickering and solving problems the dragon riders really should have figured out ages ago, like how to hold a dragon-bonding ceremony without the newly hatched dragons inadvertently eviscerating half the candidates. Lessa accidentally discovers dragons can time travel, which I guess the dragons had forgotten to mention. This is lucky, because the dragon riders are understaffed and now they can get more dragons from the good old days when dragon riding was cool. Like “Hawk Among the Sparrows,” this story thinks life would be better if we could go backwards. Also, McCaffrey’s prose has not gotten less clunky. Somehow this won a Nebula over the Delany, and I have questions.

Before starting this reading project the only Brian Aldiss I’d read was Billion Year Spree, his history of science fiction. Two stories in, I look upon his work with weary dread. “Total Environment” is a story about India written by a white British guy in the sixties. I’ll say this for it: it’s not as racist as “The Eskimo Invasion.” This is not the same thing as not racist.

25 years ago United Nations scientists sealed 1,500 Indians into a giant tower block called the Total Environment. (All volunteers; there was a famine at the time and the UN shovels in enough food for everyone.) In that time four generations have been born and the population has ballooned to 75,000. This is meant to encourage psychic powers. “High-density populations with reasonable nutritional standards develop particular nervous instabilities which may be akin to ESP spectra,” explains an alleged scientist.

As the Total Environment got more crowded it went all Lord of the Flies. Life spans dropped; people are middle aged at 20. Criminal bosses run each floor and fight wars with each other. People are kidnapped into slavery. There’s a lot of talk about rape and mentions of incest. No one tries to escape and no one even thinks about the outside world. “Hinduism had been put to the test here and had shown its terrifying strengths and weaknesses,” we’re told. “In these mazes, people had not broken under deadly conditions—nor had they thought to break away from their destiny. Dharma—duty—had been stronger than humanity.” It’s because they’re foreign, don’t ya know.

Aldiss’ hero, Thomas Dixit, is Anglo-Indian. The story defines his character by the Anglo part. He’s afraid four generations of separation are turning the Environment’s inhabitants alien. On the surface, “Total Environment” implies anybody dumped into the Total Environment would evolve into psychic weirdos. Everyone instinctively looks for new horizons. If they’re prevented from looking outward they’ll look inward, into the very small and into their own minds. But the details are racially coded and their powers are depicted with a hefty dose of orientalism. The power we get to see is the ability to kill remotely, and the story tells us “It had long been known that African witch doctors possessed similar talents, to lay a spell on a man and kill him at a distance; but how they did it had never been established; nor, indeed, had the fact ever been properly assimilated by the west, eager though the west was for new methods of killing.”

When Dixit visits the Total Environment, the inhabitants plead to be left alone like they’re pleading with a colonizer: “Tell them to go away and leave us and let us make our own world. Forget us! That is my message! Take it! Deliver it with all the strength you have! This is our world—not yours!” Dixit argues for ending the project, whatever they think. And he may be right—the Total Environment is not indefinitely sustainable. But like Rudyard Kipling, who uses the phrase “Half devil and half child” in “The White Man’s Burden,” Dixit doesn’t think of these people as adults. Speaking of a local boss who sees advantages in allying with the outside world, Dixit says “He exhibited facets of his culture to me to ascertain my reactions—testing for approval or disapproval, I’d guess, like a child.” Like “The Sharing of Flesh,” “Total Environment” has twinges of unease but comes down in favor of paternalism—as long as it’s of the right sort.

Finally we come to the story that won the Nebula for Best Novelette, Richard Wilson’s “Mother to the World.”

Oh dear.

Some stories are unjustly forgotten. “Mother to the World” is forgotten because everyone is politely not talking about it. I don’t often use the primarily moral approach to criticism, where you decide a book’s value by tallying up how it is or is not problematic. It’s usually not the most interesting or enlightening lens through which to view a story. But sometimes a story’s values are the only reasonable place to begin, and here’s one of those cases. “Mother to the World” is deranged.

It’s an Adam and Eve story. The entire human race has died and one man and one woman are left. See, what happened was China released a biological weapon that reduces human beings to powder, and… uh, the wind blew it back in their faces. (Really.) Anyway, there are no corpses to deal with. Martin Rolfe, an editor, and Siss, a housekeeper, survived because they were staying at a NASA scientist’s house. The only unused rooms were environmentally sealed rooms with their own air supplies. And… the people dissolver spread all over the world in a few hours, then went inert, I guess? None of this bears thinking about, but at least it doesn’t bear thinking about because it’s silly and not because it’s offensive. This can’t be said for the rest of the story.

Remember the Cold Equations stories? The ones that contrive farfetched situations forcing the protagonist to do something awful that is somehow not their fault? Adam and Eve stories are almost always Cold Equations stories. It’s generally a dude asking “What if a woman was, like, morally obligated to sleep with me?” “Mother to the World” is one of these. Richard Wilson’s unique twist is that Siss is mentally handicapped and has “the mentality of an eight-year-old.”

At this point you’re probably asking “does he really go there?” The answer is yes. Yes, he does. Which raises all kinds of questions about consent and relative power, which the story doesn’t attempt to answer because it didn’t notice it raised them.

When I read fiction my standard policy is to assume the writer means well. If I try very hard I can sort of guess what Wilson was going for here. Early in the story Rolfe tells himself he’s more valuable than Siss because “he was smarter than she was and therefore more worth saving.” And I think Wilson’s intent was that Rolfe learns Siss’ value as a human being does not depend on her IQ, and Siss teaches Rolfe the meaning of love. (The story ends with their son asking “Is this what love is?”) If so, it doesn’t work.

This story can’t get past the fact that its central relationship is wildly, creepily imbalanced. To be fair, Siss often comes off less like a person with literally “the mentality of an eight-year-old” and more like a naïve and poorly educated but still functional adult. But she has a go-along-to-get-along personality and at no point is she an equal partner in this relationship, which slips creepily from guardian-and-ward to marriage. The story contrives to give Rolfe a relationship in which he’s completely dominant and gets to make all the decisions.

On the prose level “Mother to the World” is actually well written. There are vivid images and observations: “Several times he found a car which had been run up upon from behind by another. It was as if, knowing they would never again be manufactured, they were trying copulation.” The story has its own voice distinct from its characters; it’s able to switch registers when it quotes Rolfe’s journals. In places the prose rises to the lyrical, and the story manages to feel intermittently mythic without being at all overblown.

But this story’s values are alien. It kept tripping me up with its weird assumptions. Like, at one point Rolfe is planning how to keep his proposed family clothed (which doesn’t seem like a problem given the vast stocks of clothing that won’t be wearing out anytime soon). He jumps to the conclusion that “Nudity might be more practical, as well as healthier.” Um, okay, dude, you do you. And there’s the moment Rolfe tells his son if he ever has to choose between saving his father or his mother he should save his mother, because…

At this point you are probably again asking “does he really go there?” And, people, I have learned two things about Richard Wilson:

- In his day job, he was director of the news bureau for Syracuse University.

- “There” is a place he was always willing to go.

“Mother to the World” is rarely reprinted, for reasons I hope are obvious. [3] I’ve rarely read a story so oblivious to how uncomfortably weird it is. It feels like Richard Wilson thought he’d written an uplifting parable about love and valuing other human beings, and was blissfully unaware it was a total creepfest.

The danger of writing characters who fail to comprehend each other is that their writers may fail to comprehend them themselves. Brian Aldiss thinks of the Indian inhabitants of the Total Environment as alien, like the Loarra. He writes according to his surface preconceptions about how an “Indian” society should look, with holy men and universal fatalism (nobody is interested in the outside?) instead of rendering them in their full complexity. Richard Wilson wants to understand Siss but fails, so fails to realize her relationship raises thorny questions of power and consent. Aldiss and Wilson haven’t thought through these characters or gotten into their heads. They’re not supporting characters, they’re props.

At least it didn’t take many votes to put “Mother to the World” in first place. I was looking for references to the story on Google Books and found an excerpt from The Business of Science Fiction by Mike Resnick and Barry Malzberg. Malzberg was nominated for “Final War” (as K. M. O’Donnell) that year. He explains the Science Fiction Writers of America was a small organization in the 1960s and the Nebulas used a first-past-the-post voting system, so it took very few votes to win. “Mother to the World” took the trophy with 19 votes. So only 19 people thought the creepy Adam and Eve story was the best Novelette of the year.

But, honestly, that’s 19 too many. And it was nominated for both awards, as was “Total Environment.” And I wonder: are SFF shortlists any better now, or is 21st century SFF just strange in ways that aren’t obvious to us? Which of today’s Hugo and Nebula nominees will make tomorrow’s readers feel weird and uncomfortable?

-

The line workers get along great. The one odd note is that they keep reminding Blacky he’s Black, even giving him, y’know, that nickname. Maybe Delany thought the readers wouldn’t notice Blacky was Black unless he really hit them over the heads with it. ↩

-

If you need to know whether the dog dies, this is not the story for you. ↩

-

To get hold of it I bought a used copy of Nebula Award Stories 4, which includes a few other rarely-reprinted stories so wasn’t a bad deal. ↩

One thought on “The Venn Diagram of Science Fiction and Fantasy Awards: 1969”

Comments are closed.