The science fiction and fantasy genres love awards. They have two big ones, the Hugos and the Nebulas, and both hand out trophies for short stories, novels, novellas, and novelettes, the last two being stories longer than short stories but shorter than novels. You might ask, “Science Fiction, why do you need two words for stories bigger than short stories but shorter than novels? Why can’t you get by with one?” Listen, these people love trophies, okay?

It’s surprising how often these award winners drop out of sight. Not so much the novels, although there are definitely Hugo and Nebula winning novels whose stars have fallen. But pretty much all short SFF feels immediately irrelevant. A story wins a Hugo, or a Nebula, and next year it’s just… not part of the conversation anymore. Well, okay, short stories in any genre haven’t been popular for decades. And the extent to which there’s a cultural conversation around written SFF at all isn’t great. But when people do talk about short SFF they’re usually talking about short SFF still new enough to nominate for something. As soon as award season is over it drops off the radar.

So I’ve been looking for some direction for my reading, and I thought it might be interesting to read some older SFF award winners, most of which I haven’t read in many years if at all. Specifically, stories that made the shortlists for both the Hugos and the Nebulas. These are popular awards, but popular within a subculture. The Hugos are voted on by the few hundred or thousand SFF fans who attend science fiction conventions, and the Nebulas are voted by members of a professional group, the Science Fiction Writers of America. So these awards don’t quite represent the tastes of the much larger group of readers who will pick up some fantasy novels at the library but aren’t interested in arranging their social lives around them. Still, the overlap between the two shortlists is probably a decent guide to what made an impression on readers at the time. Do they hold up, or are they deservedly forgotten? We’ll see.

A few notes on this series:

- This project will cover novellas, novelettes, and short stories, and few if any novels. Including novels would involve a lot of reading. More to the point, it would involve reading a lot of books life is too short to read again, or at all.

- I’ll only write in detail about joint winners, or other stories I find interesting. Otherwise future posts will be broad summaries of whatever themes I noticed in that year’s stories.

- The series will be written slowly and posted irregularly, and will continue until I get bored or distracted. I’ve got to be honest, I may not get out of the 1960s here. I’ll stop before I reach the 2010s in any case, since it’s harder to have critical perspective on writing from the last decade.

- I can’t promise it will be comprehensive. I’m an amateur critic writing for my own amusement, and if I have trouble finding a story I’m only willing to go to so much trouble and expense to track it down.

That said, let’s start with:

1966

1966, the first year Nebulas were awarded, makes for an easy start: only two stories were both Hugo and Nebula nominees (along with Frank Herbert’s Dune in the novel category; it won the Nebula and tied with Roger Zelazny’s This Immortal for the Hugo). That might seem hard to believe given the Nebulas’ overstuffed first-year shortlists—27 stories in the short story list alone—but that year the Hugos had only one category for short fiction. By the time they expanded, the Nebulas had figured out how to trim their shortlists to a sensible half dozen entries. Nevertheless, future years will feature longer lists of shared nominees.

So the obvious place to start is Harlan Ellison’s “’Repent, Harlequin! Said the Ticktockman,” which won both the Hugo and Nebula for best short story in 1966. (For stories published in 1965. This series is going by the dates of the awards; the stories in each post will have been published in the previous year.) And having asserted old short SFF isn’t part of the cultural conversation I must admit we have an exception here, at least to the extent that “Repent, Harlequin” is obviously being taught in literature classes: Google it and you get pages of prefab essays for incompetently lazy students to plagiarize.

Which is weird, because you’d think students wouldn’t need the help. Ellison starts “Repent, Harlequin” by flat out telling you what it’s going to be about. “For those who need to ask, for those who need points sharply made, who need to know ‘where it’s at,’” he pastes in a long paragraph from Thoreau’s “Civil Disobedience.” Which also tells you about its tone. It is, first, looking for a fight. A narrator immediately certain his readers are demanding to know “where it’s at” feels like the kind of guy who’d shout “What are you looking at?” at people who hadn’t even noticed he was there. (Harlan Ellison has a distinctive voice, and this would be a big part of it going forward.) At the same time there’s something playful about a story that provides its own Cliffs Notes.

“Repent, Harlequin” is set in the capital-S System, a society so monomaniacally efficient its systems have no give at all. So it notes whenever anyone is late for anything and deducts the time from their projected lifespan; rack up enough lost minutes and the Ticktockman shuts your heart off by remote control. The Harlequin dresses up as a jester to prank the System by, for instance, gumming up the moving sidewalks with $150,000 worth of jelly beans. The story asks where he got $150,000 worth of jelly beans, then admits it doesn’t care. Jelly beans are the thematically right tool for the job and their origin is thematically irrelevant, so the Harlequin just has them. It’s fiction. Deal with it.

It’s not hard to see why Ellison felt like writing about civil disobedience in 1965. The civil rights movement was winning real victories (Lyndon Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act in August) and opposition to the Vietnam War was picking up. What’s more surprising is a synchronicity with something that hadn’t happened yet, though it would be part of the cultural context for the Hugo and Nebula voters. Namely, the premiere of the Adam West Batman in January 1966. “Repent, Harlequin” is a superhero story about a costumed crusader facing off against a masked villain, and like Batman it’s self-aware and self-parodying. The jelly bean incident is followed by a deflating domestic scene in which the Harlequin’s relatively normal girlfriend takes the piss out of his overdramatic dialogue and (accurately) points out how ridiculous he is. This wouldn’t happen to the square-jawed engineers and space marines who were the stereotypical SF heroes ten years earlier.

Speaking of differences from earlier SF, maybe it’s time to talk about the prose. This is a vast oversimplification, but fans and critics tend to divide mid–20th-century SF into two distinct periods, the “Golden Age” (the 1940s through the 1950s) and the “New Wave” (the sixties through the early seventies). One difference between these eras was stylistic. Most Golden Age SF writers wrote slapdash pulpy prose meant to deliver a plot reasonably clearly, without much attention given to the work the prose was doing beyond simple description. (Advocates call this “transparent prose.” The idea is the prose is a “window” through which you watch the story without noticing the glass.) The New Wave writers’ tastes were more literary and they paid more attention to how language communicates feelings and images beyond its surface meaning.[1]

Ellison was a New Wave writer with a distinct voice, and knew how to make words work for him. When writing about the Ticktockman the prose keeps a regular rhythm, short sentences, or short phrases separated by commas: “You don’t call a man a hated name, not when that man, behind his mask, is capable of revoking the minutes, the hours, the days and nights, the years of your life.” The confrontation between the Harlequin and the Ticktockman is a metronomic tennis-match back-and-forth dialogue. During the jelly bean assault the narrative begins straightforwardly, speeds up to a run-on sentence as the Harlequin looses his beans, switches to short choppy single-sentence paragraphs when the System notices its schedule is off, and goes openly exasperated, all italics and question marks, as it asks what is going on? Every line of “Repent, Harlequin” is crafted to not only describe what happens but express how what is happening feels.

The prose carries you along like a carnival ride. It’s not until the ride is over that you might start to poke at it. “Repent, Harlequin” has, arguably, failings matching the weak points of left-wing culture in the late 1960s.[2] You might wonder whether scheduling, that tool of The Man, is pernicious enough to invite parody; if you asked me to list the problems with a regimented, unequal, surveillance society, things happening at predictable times would be far down the list. In Paingod and Other Delusions Ellison admitted to being chronically late and pointed out the similarity between Harlequin and Harlan; he’s not protesting injustice here so much as something that’s just harshing his mellow.

You might discern an uncomfortable, reflexive disdain for squares. (See again that opening line, presuming a fight the reader wasn’t actually picking.) When the Harlequin buzzes a crowd they faint and wet themselves, and there’s that bit of Thoreau: “In most cases there is no free exercise whatever of the judgment or of the moral sense; but they put themselves on a level with wood and earth and stones; and wooden men can perhaps be manufactured that will serve the purpose as well.”

And maybe “Repent, Harlequin” has a slightly too naïve faith in the power of protest: those Vietnam protests went on for years, involved tens of thousands of people, and did nothing to stop the war. Civil disobedience isn’t a virtue in itself but a tactic, which can be deployed effectively (as the Civil Rights movement did) or ineffectively (all those Vietnam protests). And it’s not clear the Harlequin was effective. As his costume suggests his pranks are in the spirit of carnivalesque protest—balloons and giant puppets, billboard détournement, attempts to levitate the Pentagon, the kind of street protests that shade into street parties—which was popular with a large chunk of the activist left who opposed the war. Say, the Youth International Party (Yippies), who would get their start in a couple of years. But the point of medieval carnivals, with their reversals and tweaking of authority, was that they didn’t challenge the system, just acted as a release valve. After Carnival was over everything went back to normal. “Repent, Harlequin” says “if you make only a little change, then it seems to be worthwhile,” but the little change is that the Ticktockman is three minutes late… which he just denies. “Check your watch.” Who’s going to argue? This is still the guy who can revoke the minutes of your life. Your watch says what the Ticktockman says it says, because the Harlequin did not at any point tip the balance of power and the moral of the story doesn’t account for that.

That said, the prose does carry you. It’s a good ride.

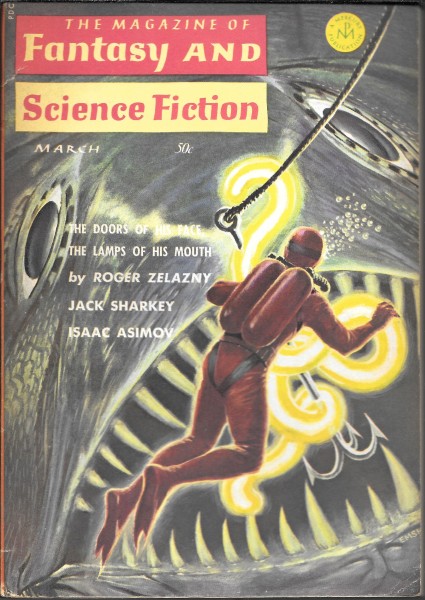

“The Doors of His Face, the Lamps of His Mouth”, by Roger Zelazny, is an evocative title for what is basically just a fishing trip. But it earns the title. Zelazny was having a good year. In addition to tying for the best novel Hugo, his “He Who Shapes” tied with Brian Aldiss’ “The Saliva Tree” for Best Novella at the Nebulas.

The title comes from the book of Job, in which God brags about this awesome fish he made:

10 None is so fierce that dare stir him up: who then is able to stand before me?

14 Who can open the doors of his face? his teeth are terrible round about.

19 Out of his mouth go burning lamps, and sparks of fire leap out.

You can find leviathans on Venus. They haven’t yet been caught. Carl Davits tried, and was so awed by the Godzilla-sized fish he froze and couldn’t press the Fish Catching Button. Now he’s been hired as a bait man by Jean Luharich, his ex-wife, who’d like a big fish herself.

“Doors” is an old-fashioned adventure story with lots of technical detail about how a 300-foot fish is caught. (It’s not quite as simple as pressing a button. But there is a button. It’s very Jetsons.) But as with “Repent, Harlequin” it’s the style that matters. Carl has a poetic soul and his descriptions of Venus—how the sky looks at sunrise, what it’s like to approach from orbit—are vivid. Sometimes he slips into self-parody; the story’s last words are “the rings of Saturn sing epithalamium the sea-beast’s dower,” and I defy anyone to read this story without having to look up the word epithalamium. But I think this is more characterization than clumsiness on Zelazny’s part. What makes Carl memorable is the contrast between his inner monologue and his outer presentation as a rough port bum, as when he’s asked what it’s like diving at night:

I puffed, thinking of my light cutting through the insides of a black diamond, shaken slightly. The meteor-dart of a suddenly illuminated fish, the swaying of grotesque ferns, like nebulae-shadow, then green, then gone—swam in a moment through my mind. I guess it’s like a spaceship would feel, if a spaceship could feel, crossing between worlds—and quiet, uncannily, preternaturally quiet; and peaceful as sleep.

“Dark,” I said, “and not real choppy below a few fathoms.”

There’s a The Old Man and the Sea vibe to this story. It’s about humans pitting themselves against nature to prove their courage. But unlike Hemingway it’s not exclusively masculine; the gender politics are not modern but for a mid-sixties SF story (and that’s a big caveat) they aren’t bad. Jean organized this expedition as a publicity stunt for her cosmetics company, but her marketing is about adventure and heroics more than beauty. And she’s a competent adventurer. Their marriage failed because she and Carl were too alike.

If “The Doors of His Face” feels old-fashioned it might be because it feels like a screwball comedy. A critic named Stanley Cavell once identified a subgenre popular in the 1930s–40s called the “comedy of remarriage.” Examples are The Awful Truth and His Girl Friday (Cary Grant turns up in them a lot). They’re about couples who split up at (or before) the beginning of the movie but realize they belong together at the end; they were a way to create an exciting but Hayes-code-friendly simulation of infidelity as the couple dally with potential new partners. Structurally that’s what we have here. Jean also freezes at the vital moment, but because Carl is there to give her some “you can do it” encouragement she unfreezes and presses the Fish Catching Button that defeated him. (If landing the fish seems absurdly simple, it’s probably to keep a hundred percent of the reader’s attention on the drama.) And, well, that’s where the epithalamiums come in. Once you notice this it’s hard not to imagine “The Doors of His Face” as a black-and-white movie, with Katherine Hepburn as Jean and Robert Mitchum as Carl, with leviathans by Ray Harryhausen.

The one thing “The Doors of His Face” doesn’t resemble in the slightest is the book most critics claim as an influence: Moby-Dick. It’s not Moby-Dick, people. I assume you’re all saying this because you’ve never read Moby-Dick but it’s the only book you can think of about a giant sea creature. Moby Dick is unconquerable Nature. The leviathan is a big Filet-O-Fish. Who can open the doors of his face? Apparently these people. “The Doors of His Face” is New Wave in style but its heart is still in the Golden Age; it doesn’t doubt humans can conquer anything.

So I found the politics of “Repent Harlequin” a touch naïve, and called “Doors of His Face” old fashioned. Am I saying these stories aren’t worthy award-winners after all?

Oh, hell, no. These are great. “Doors” is less likely to reveal new facets on rereading—“Repent, Harlequin” is literature, “Doors” is an adventure yarn that just happens to be really, really well done. But they’re both classics. It is, again, all about style. Roger Ebert had a maxim he called Ebert’s Law—I think he might have codified it in a review of a movie called Freeway—that states “A movie is not about what it is about. It is about how it is about it.” The same is true for stories. This lesson is, unfortunately, still lost on a lot of SFF, especially at novel length. Scores of novels are published every year that bury a few interesting ideas within but are written like plates of limp noodles with no sauce at all. You can’t say that about these stories; as unimpressed as I am with Dune, I’d say the award voters did pretty well in 1966. On to 1967 in… maybe a couple of weeks? We’ll see.

“The series will be written slowly and posted irregularly, and will continue until I get bored or distracted.â€

If encouragement will help, here, have some! I would love to read more of these.