(I’ve been reading the stories that got both Hugo and Nebula nominations. To see all the posts in the series, check the “Joint SFF Nominations” tag.)

Okay. At this point the sixties are over (although the “long 1960s” would drag on for a couple years yet). America is still in Vietnam, Nixon is in the White House, the left has not made a dent on these problems, and everyone’s tired. Stories are asking: what do we do with a broken world? Tear it down? Wait it out? Deep time and patience are recurring themes. SFF is taking the long view in:

1971

The novels that got both Hugo and Nebula nominations in 1971 were Larry Niven’s Ringworld, Robert Silverberg’s Tower of Glass, and Wilson Tucker’s The Year of the Quiet Sun. Ringworld took both awards, although it’s a well-done but lightweight adventure novel rather than anything with ambition.

The stories nominated for both awards were:

- Harlan Ellison, “The Region Between”: A dead man’s soul is transplanted into a series of alien bodies, and he is not having it.

- R. A. Lafferty, “Continued on Next Rock”: A team of archaeologists don’t notice an ancient story repeating itself in their midst.

- Keith Laumer, “In the Queue”: A guy stands in line. It’s a long line, people.

- Fritz Leiber, “Ill Met in Lankhmar” (Won the Hugo and Nebula for Best Novella): A barbarian and a thief get drunk and attempt a half-assed infiltration of the local thieves’ guild. Meanwhile, a wizard fridges their girlfriends.

- Clifford D. Simak, “The Thing in the Stone”: A man in rural Wisconsin discovers an alien mind trapped in the landscape.

- Theodore Sturgeon, “Slow Sculpture” (Won the Nebula for Best Novelette and Hugo for Best Short Story): A woman with cancer meets a man with a cure.

First, I’d like to note that for the first year since 1966 none of the double-nominated stories involve racism or creepy sex. Yay, science fiction! I knew you could do it!

Second, this is a good year. The Ellison, Lafferty, Simak, and Sturgeon stories are legitimately great. The Laumer and Leiber stories are, at worst, average.

And, honestly, my disregard for “Ill Met in Lankhmar” may be a matter of taste. This story stars Fafhrd and the Grey Mouser, sword and sorcery[1] heroes whose adventures spanned several volumes and decades. I like a lot of Leiber’s work so I’ve tried to get into this series before, but it bores me. Fafhrd and the Mouser aren’t interesting characters. They’re shallow; nothing they do or think is a surprise. There’s nothing to them beyond their adventuring skills and Vancian speech patterns. Leiber’s prose is as good here as anywhere else, but his subjects feel like a teenager’s Dungeons & Dragons characters.[2]

Leiber wrote “Ill Met in Lankhmar” after decades of stories about Fafhrd and the Mouser. To fans, it must have been an event: this is their origin story, their very first adventure together.[3] What’s interesting is that Leiber doesn’t make them look good. These guys are screwups. Fafhrd and the Mouser meet cute stealing already-stolen gems from fellow thieves. They haul the spoils to the Mouser’s place and introduce their girlfriends to each other. Fafhrd’s other half has a grudge against the Thieves’ Guild and convinces the pair to take action stronger than loot hijacking. They get drunk and attempt a half-assed infiltration of the Guild headquarters, where they watch slack-jawed as a wizard casts a spell. Returning home they discover it was a spell to recover the gems, which incidentally killed their girlfriends. They return to the Guild, kill some people, and run away again. The end.

This story is pointless. It’s not about anything. It’s just… well, a description of some things that happened to the characters, which are assumed to be exciting in themselves in the absence of subtext. Which is a problem if you aren’t interested in these characters and don’t care what happens to them.

I’m getting “Ill Met in Lankhmar” out of the way first because it’s an outlier. It doesn’t share many themes with other stories in this batch, mostly because it has no theme except “look at this gritty adventure.” Unless the theme is “roguish sword and sorcery antiheroes are doofuses, actually,” which is a message I can get behind.

Themes that recur in the other stories include repeating cycles, reincarnation, deep time, geology, and patience. And several stories ask the question: how do you respond to a bad society, and power misused?

There is No Alternative

The simplest is Keith Laumer’s “In the Queue.” People line up to get their documents processed at the world’s only document-processing window. They wait for years—sometimes their whole lives. There’s nothing beyond the line but a wasteland. Hestler is one of the lucky few to reach the window. His business concluded, he walks all the way to the end of the line… and gets in line again. That’s where everyone he knows lives; that’s his world. It’s a bad world, but it’s the world Hestler has; he can’t imagine an alternative.

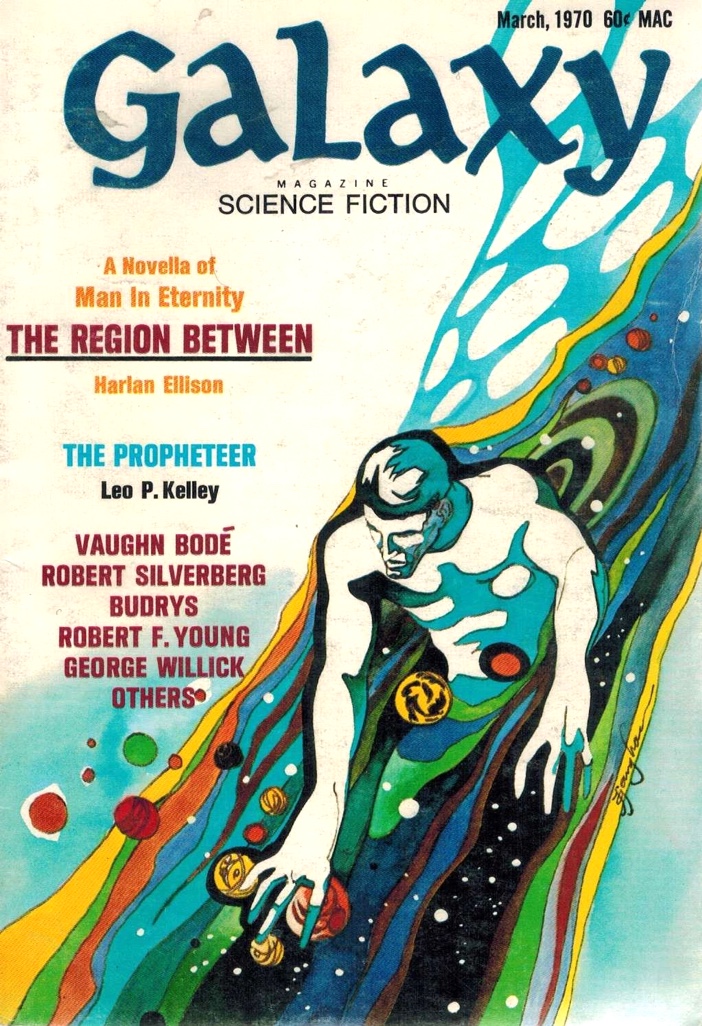

Laumer also contributed to Harlan Ellison’s “The Region Between,” which is a lot of fun and miles better than “A Boy and His Dog.” Ellison wrote “The Region Between” for an anthology called Five Fates. The gimmick was that Laumer wrote a prologue in which William Bailey receives a disappointingly impersonal injection at a Euthanasia Center. Laumer, Ellison, Poul “Sharing of Flesh” Anderson, Frank “Dune” Herbert, and Gordon “Call Him Lord” Dickson each wrote a novella starting from there. In this bunch Ellison sticks out like a neon orange thumb: he delivered a drunkenly typeset romp with text scattered sideways, upside down, backwards; spiraling paragraphs and dollops of concrete poetry; and a paragraph where the words of one sentence slip in between the words of another; all framed—in the story’s preferred form—by graphic layouts and illustrations by Jack Gaughan.

A lot of SF predicted something like “Euthanasia Centers” around 1970—see for example Soylent Green,loosely adapted from Harry Harrison’s 1966 novel Make Room! Make Room!. Harrison’s novel contains neither euthanasia centers nor cannibalism. That they were added to the movie just four years later may be down to the late sixties’ increasing anxiety about overpopulation. Paul Ehrlich’s 1968 bestseller The Population Bomb popularized the idea (which had been floating around at least a couple decades) that population growth was a major environmental problem. The human population, argued Ehrlich, was on the verge of outstripping the Earth’s resources; he predicted mass starvation by the end of the seventies. Obviously this didn’t happen—Ehrlich didn’t account for the fact that an environment’s carrying capacity can change—but by the end of the sixties imagined futures were often overcrowded. SF writers didn’t have much faith that governments’ response would respect human life.

In “The Region Between,” the Euthanasia Centers were engineered by an alien entity called “the Succubus” to harvest souls, a hot commodity in the wider universe. Some unknown people steal them. The Succubus brokers replacements. Bailey is plugged into a succession of bodies—the story’s collaged layout reflects his fragmented, disjointed new existence. First he’s a soldier sent on a false flag mission designed to extend a war—both sides’ rulers feed off the death. Bailey manages to hold onto his true identity, and almost manages to stop it. In his next couple of bodies he’s more successful at sabotaging a mission of conquest and an alien cockfight. “Did you ever stop to think how many individuals and races like to play God?” asks Bailey. Everyone Bailey inhabits is critical to powerful people who prey on the less powerful, and every time he manages to screw up their plans.

(All the victims’ souls are stolen at exactly the most critical moment. Are the soul thieves revolutionaries?)

(Also: the word Succubus comes from succubare, “to lie beneath.” Does the Succubus underly the powers that be—i.e., is his work the foundation of their power?)

The universe was created by a God who left his fingerprints all over it: “Godness lies dormant yet remembered in every thing, every smallest thing, in every puniest creature.” “God is in everyone” is usually an inspirational bromide, but not here: the God part of us is the part that wants control, sees other people as resources. Bailey, though, has more God than average. When the Succubus takes a closer look at Bailey’s soul God himself emerges from it. And when he sees the world of predators and prey the universe has become, he ends it. Typically for Ellison, this is an angry story. Bailey’s alternative to a sick society is to blow it up, tear everything down. The inevitable result of a universe where everyone wants to play god is that eventually only one god is left. Bailey started out trying to destroy himself; now he’s reduced the universe to nothing but himself.

Time and Stones

“The world gets new rocks all the time. But it’s the same people who keep turning up, and the same minds.”

The theme “Continued on Next Rock” shares with “The Region Between” is repeated returns from death, although not of the same kind. R. A. Lafferty is writing about deep time, living myths, and eternal returns happening in the background of an archaeological trip to a chimney rock leaning on an ancient Native American mound. (A reference in the story compares it to the Spiro Mounds in Oklahoma; Lafferty lived there and his stories are often deeply connected to the landscape.)

Where Ellison is angry Lafferty is strange. His most characteristic stories are celebrations of strangeness. The thing about Lafferty is that he’s… well, completely himself. SFF is mostly market-shaped, crafted to sell to a particular audience or editor. Lafferty tears inscrutable literary contraptions straight out of his heart and brain, and places them before you, and you can take them or leave them. He won’t show up much in this series; rarely is the same Lafferty story nominated for both a Hugo and a Nebula.[4] Lafferty is among the greatest SFF writers of the 20th century, but also among the most esoteric; not everybody can tune in on his wavelength.

Lafferty’s prose has the rhythm of screwball comic patter—you can imagine a Lafferty audiobook read by Groucho Marx—but he can segue into higher registers when needed. He has a complex vocabulary but writes simple prose. Not transparent prose—his stories have narrators, with points of view. Lafferty is a teller of tall tales. A lot of his characters are exaggerated legendary heroes. Like Magdalen, the expedition’s grad student. Magdalen knows things she couldn’t possibly know, like all of what’s in the mound and the chimney. And she’s strong enough to carry a 190 pound deer back to camp on her shoulders. And though she’s the least senior person there, everybody instinctually does as she says: “Magdalen had no right to give orders to anyone, except her born right.”

(Lafferty also has a nice line in comically nasty rogues. But he writes most sympathetically about people on the margins—misfits, if not literally marginalized. Which has a lot to do with why, although Lafferty himself was conservative, his stories often feel progressive. Lafferty is on the side of the oddballs. His dearest wish is that everybody should cultivate their inner weirdness.)

A “rich old poor man” named Anteros Manypenny appears at dinner and offers to dig. He digs perfectly, and knows what he’ll dig up before it’s uncovered. Magdalen’s unimpressed. “He’ll just uncover some of his own things,” she says. Magdalen and Anteros know each other, not that the archaeologists pick up on this. The narrator doesn’t pick up on it, either. Magdalen and Anteros know more than the narrator does. One of Lafferty’s strategies here is to limit the narrator’s understanding of the story, and contrast it with what he wants the reader to understand. “Very often Magdalen said things that made no sense,” says this story, though it’s only her colleagues that Magdalen makes no sense to.

Each day Anteros digs into the chimney rock and uncovers a stone tablet carved with strange love poetry: “You are the freedom of wild pigs in the sour-grass, and the nobility of badgers. You are the brightness of serpents and the soaring of vultures.” The tablets are impossibly recent, written in several Native American languages centuries newer than the undisturbed sediment they’re found in. Gradually the tablets reveal a story about an earthbound being in love with someone repeatedly trying to reach the sky and falling back to earth:

It is the earth that calls you. I am the earth, woolier than wolves and rougher than rocks. I am the bog earth that sucks you in. You cannot give, you cannot like, you cannot love, you think there is something else, you think there is a sky-bridge you may loiter on without crashing down.

And then Magdalen falls from the top of the chimney, and Anteros vanishes, replaced by a statue. And everyone forgets they were ever there.

Magdalen and Anteros have been returning to repeat this story for centuries; possibly thousands of years. (And across multiple civilizations—while they’re in Oklahoma they’re tied to Native American culture, but Anteros is a Greek name and Magdalen is Biblical.) It doesn’t feel like Anteros is stalking her—Magdalen’s capable of dealing with attention she doesn’t want, and her insults to Anteros feel good-humored, like she’s acting out a role. This is a ritual. It’s somehow necessary that Magdalen and Anteros play out this drama of rebirth and sacrifice. Why isn’t clear, but neither are giving up on their work.

Clifford Simak begins “The Thing in the Stone” by contrasting two people. Wallace Daniels moves to rural Wisconsin to recover from a car accident. (Even more than Lafferty’s, Simak’s writing is powerfully tied to his home region and to the landscape, which has a major role in his stories.) “He walked the hills and knew what the hills had seen through geologic time,” says Simak, and the first paragraph continues in that poetic vein; Daniels is sensitive and curious and spends his days exploring his property and tending his chickens and cows. Then we’re told “his next-door neighbor, a most ill-favored man, drove to the county seat, thirty miles away, to tell the sheriff that this reader of the hills, this listener to the stars was a chicken thief.”

This doesn’t come to anything, because the sheriff isn’t stupid. But Ben Adams won’t give up his weird grudge; he thinks Daniels is Up To Something. Daniels wanders his land like he’s searching: for treasure, maybe? What he really sees is deep time. Daniels’ accident left him with powers. He sees through time, seeing the landscape as it was millions of years ago (and sometimes travelling back bodily). If he concentrates on the stars he hears messages sent between alien civilizations. And in one particular cave he hears an alien being trapped beneath the stone.

One cold night, with a dangerous snowstorm coming up, Adams pulls Daniels’ rope away, trapping him in the cave. Desperate, Daniels manages to contact another, incorporeal alien, some loyal follower who watches over the thing in the stone and wants to set it free. Then Daniels manages to shift back a few million years, allowing him to escape the cave (because the prehistoric landscape is different) and incidentally see the thing in the stone arrive. It’s a criminal, and Earth is its prison.

Simak’s prose is deceptively simple. Like Lafferty’s prose it feels like speech, though of a different kind; it’s plainspoken folk storytelling where Lafferty is a vaudeville comedian. It’s carefully crafted without seeming to be, so it’s worth looking at a couple of short paragraphs more closely:

And suddenly in this place of one-sound-only there came a throbbing, faint but clear and presently louder, pressing down against the water, beating at the little island—a sound out of the sky.

Daniels leaped to his feet and looked up and the ship was there, plummeting down toward him. But not a ship of solid form, it seemed—rather a distorted thing, as if many planes of light (if there could be such things as planes of light) had been slapped together in a haphazard sort of way.

Simak’s prose has a calm and measured rhythm. Sometimes he falls into iambs or trochees for a phrase or two before resuming a more naturally irregular stress pattern: “pressing down against the water, beating at the little island.” That’s also parallel phrasing, as is “this reader of the hills, this listener to the stars” from the introduction. Simak uses repetition of phrasing or repetition of words as a speaker might use them for rhythm or emphasis (see also “He walked the hills and knew what the hills had seen through geologic time”—not every writer would have repeated “the hills” there). “Daniels leaped to his feet and looked up and the ship was there” feels like the narrator is talking faster, with the way it stacks “and” conjunctions without commas. And the last phrase “haphazard sort of way” is a phrasing you might use in casual speech—“sort of” is a filler, and also suggests “haphazard” is a word chosen off the top of the narrator’s head, and might not be quite right.

When Daniels returns to the present and meets a search party, he lets Adams know he knows what Adams did. But he also chooses not to give Adams away to the sheriff. He’s giving Adams a chance to be better. (Earlier, of the fox stealing both Adams’ and his own chickens, Daniels said “I figure we are neighbors… Maybe that means I own a piece of him.”) He goes home with his new alien friend. He’s interested in seeing Daniels care for his animals, leading Daniels to a realization. The alien isn’t the thing’s follower, it’s a guardian and minder—as Daniels puts it, a “shepherd.” The aliens deal with evil by keeping it harmlessly contained, but never giving up on the possibility it might be redeemed, even if it takes a few million years.

Patience

“Slow Sculpture” is about a man and a woman whose names we never learn because they don’t ask them of each other until the story ends. The woman has a cancer diagnosis and goes for a walk to clear her head, where she meets the man making scientific observations on a tree. He offers to help; she has nothing to lose, so follows him to his lab. The treatment involves electricity (the man was also measuring electrical current around the tree) and surprisingly seems to work—definite proof will come with time, but she has her own reasons for believing he’s pulled off a miracle. She asks why, if he has this cure, he hasn’t told anyone.

It turns out the man has lived out the urban legend of the inventor whose super-efficient carburetor gets bought and buried by a car company. This is a repeated pattern in his life. He has great ideas, they get shot down because people just aren’t ready for him. He’s too real, man. He knows how it’s going to go if he tries to tell people about his cancer cure: all anyone will see is that he’s not a doctor, and he’ll be branded a quack. His lab is full of inventions that could change the world, and never will. Getting people to listen is hard. He’s stopped trying.

The man likes trees. The centerpiece of his home is a very old bonsai. He’s learned how to care for it, how to make the endless small adjustments that guide it to grow into something beautiful:

A man sees the tree and in his mind makes certain extensions and extrapolations of what he sees, and sets about making them happen. The tree in turn will do only what a tree can do, will resist to the death any attempt to do what it cannot do, or to do it in less time than it needs. The shaping of a bonsai is therefore always a compromise and always a cooperation… It is the slowest sculpture in the world, and there is, at times, doubt as to which is being sculpted, man or tree.

(Sturgeon’s prose is precise but casual, colloquial in a way that might not be clear from this excerpt. This story is dialogue-driven; there’s far more conversation than action or description. It’s a philosophical dialogue.)

Like Ellison’s William Bailey, Sturgeon’s nameless engineer despairs for humanity. Where “The Region Between” is angry (not a complaint—it’s good at being angry), “Slow Sculpture” argues for patience: if you can’t get the world to listen you don’t give up on it, you try a new strategy. As the woman says, “I mean… you already know how to get what you want with the tree, don’t you?”

There’s this ongoing debate in leftist circles over the value of incremental change, or reform, versus revolutionary change. This debate makes no sense to me inasmuch as there’s no reason for reform and revolution to be versus each other. Still, there’s a certain part of the left who, when they can’t get everything they want in one giant leap, give up and go home—think of the voters who sat out the 2010 midterms after getting a public option turned out to be harder than they thought, or the small faction who refused to vote for Hillary Clinton or Joe Biden after Bernie Sanders couldn’t convince enough people he was a reliable candidate.

The problem with revolution, though, is that you rarely get the chance to pull one off. The right conditions don’t come along very often. In the meantime you can do nothing, or you can try reform: change what you can. An incremental change is still a change. If it doesn’t help everybody, it may help someone. And enough incremental changes can create the conditions for the big, revolutionary change that’s currently out of reach, like a thousand tiny adjustments shape a bonsai.

“Slow Sculpture” argues that it’s better to think of people as stubborn than stupid. Trees and human society are slow to change, and need constant tending if they’re going to change in the right way; you can’t afford to get frustrated when it proves impossible to force it. It’s not a good world, but it’s better to keep pushing whatever levers you have access to than to give up.

-

A term reportedly coined by Leiber himself. ↩

-

The Fafhrd/Mouser stories were a big influence on Dungeons & Dragons, to the point TSR licensed them for a supplement. ↩

-

Another prequel featuring only Fafhrd, “The Snow Women,” also got a Nebula nomination. ↩

-

The one time he won a Hugo was for “Eurema’s Dam,” which even Lafferty didn’t think was his best work: in an interview available online, he says “Winning the Hugo Award for ‘Eurema’s Dam’ puzzled me completely, and I’m still puzzled by it.” ↩

One thought on “The Venn Diagram of Science Fiction and Fantasy Awards: 1971”

Comments are closed.