1.

At about the age I was getting over the extreme nervousness of my early childhood I ran across Jack Sullivan’s Lost Souls: A Collection of English Ghost Stories at the library. It’s one of the best ghost story anthologies I’ve ever read—more rarities than familiar chestnuts, and every one a banger.

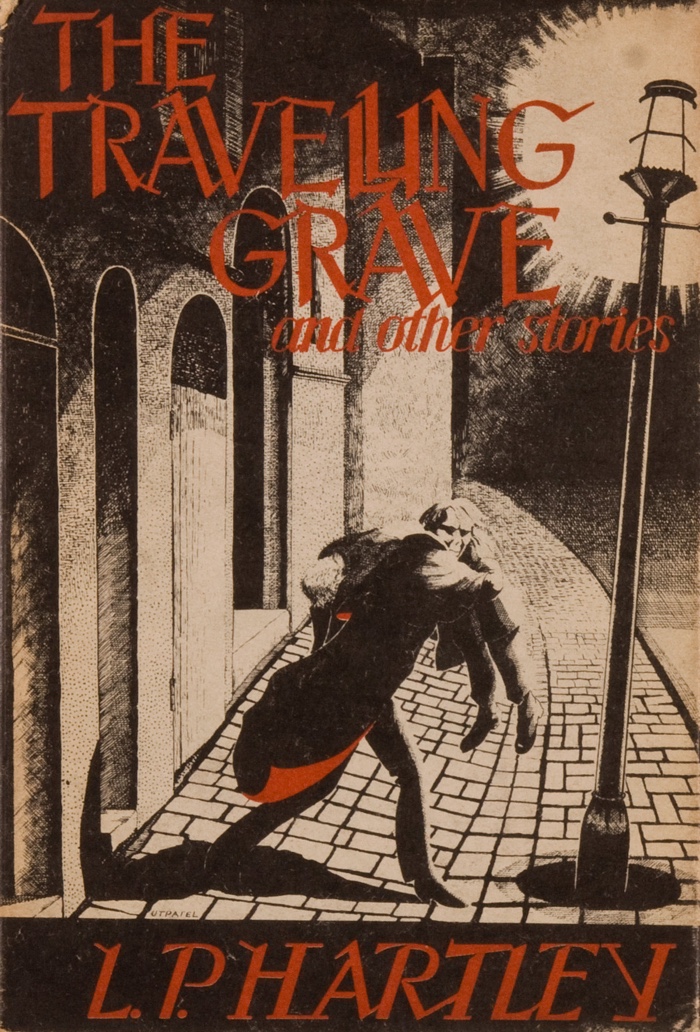

One of the many stories that stuck with me, mostly due to its absurd and singular final image, was L. P. Hartley’s “The Travelling [sic] Grave.” What’s weird is “The Travelling Grave” is not a ghost story—it’s a thriller, and arguably early science fiction—but it felt at home in Lost Souls. And this isn’t the only time it’s turned up in an anthology of specifically ghost stories—no less an authority than Robert Aickman selected it for the first volume of The Fontana Book of Great Ghost Stories.

Why does “The Travelling Grave” feel haunted?

2.

First, go read the story. It’s been reprinted all over. Hartley’s collection The Travelling Grave and Other Stories is in print from Valancourt Books. It’s the kind of ironic biter-bit anecdote Alfred Hitchcock Presents specialized in: a villain sets an ingenious deathtrap only to fall into it himself. Anyone who’s seen a few episodes of AHP or The Twilight Zone will guess where it’s going—but not how it gets there.

The first sentence introduces us to Hugh Curtis, whose name and biography are typical of Edwardian adventure stories—public school, service in the first World War, a private income and a gentleman’s club. But the same sentence suggests indecision: Hugh’s waffling over an invitation to a weekend at the country house of Dick Munt. If he’s accepted, it’s only because “they can’t kill me.” This is a habit. Ever since his school days Hugh has reassured himself that they—he’s is one of those unlucky people for whom there’s always been a “they”—can’t kill him. “With the war, this saving reservation had to be dropped: they could kill him, that was what they were there for.” But it’s peacetime again, and Hugh is back to his old habits.

So it looks like Hugh’s our hero, but this brief portrait reveals a nervous, indecisive man, and as he’s arriving late to the party he now disappears altogether.

3.

Instead we follow Hugh’s friend Valentine Ostrop. You can tell from the name Valentine is a different type of character. Hugh likes Valentine but doesn’t understand his “foppishness,” the kind of thing that at this time signaled a character was gay. (Hartley was apparently a gay man himself.) As the story goes on it becomes clear Valentine has an unrequited attraction to Hugh; later the cast will be badgered into a game of hide-and-seek and when Hugh catches Valentine the story compares Valentine to Atalanta.

Valentine’s default conversational mode is Saki-esque piffle. Munt is famous as a collector but nobody knows what he collects. As Valentine settles in with Bettisher, the only other guest, he riffs on the notion Munt collects perambulators (or, as we Americans know them, baby-carriages). This leads to a conversation at cross-purposes when Munt arrives and Valentine plays a guessing-game about his collectables—they carry bodies, they’re mostly made of wood, at some point they perform an “essential service” for everybody—Munt agrees with everything. Only when Munt says his latest self-propelled acquisition doesn’t need a sexton or a priest do we realize Valentine’s error: Munt collects coffins. The house is full of coffins. (Some contain dummies. Or maybe skeletons, which Bettisher says are a kind of dummy.)

This conversation carries on longer than seems necessary and at a certain point Valentine thinks the joke is past its sell-by date. That it sticks out is a clue that it has an important function in the story. Actually, it has three functions.

First, there’s the irony: it unifies two things as chalky and cheesy as coffins and perambulators—one comes at the beginning of life, one at the end, otherwise what’s the difference? I mentioned above “The Travelling Grave” has the same ironic structure as the median episode of Alfred Hitchcock Presents. Irony is not just the structure but the tone; it’s a story of reversals and double-meanings.

More subtly, the conversation positions Valentine and Munt as opposing forces, life and death. And it takes a joke, carries it past the point it stops being funny, then turns it sinister. This will come up again: the story rides the knife edge between funny absurdity and the disconcerting kind. Everyone talks piffle but it’s nightmare piffle. Ha ha funny repeatedly becomes funny peculiar.

4.

Cut to a freshly unpacked Travelling Grave, a wooden cube sitting on top of a tangle of machinery and knives, which seems “to move all ways at once, like a crab.” It’s designed to hunt a guy down, kill him, fold him in half backwards with the head tucked under the heels, and bury itself in the ground. Or the floor—it can drill right through wood and for camouflage Munt inlaid the lid with his own pattern of parquet.

I don’t know whether Harley knew the word “robot”—it was coined less than a decade earlier—but that’s what we have here: a killer robot that seems to anticipate a Dalek. A drone, or one of those dog-bots you can mount a rifle on with the added feature that it cleans up its own mess. This is proto-science-fiction.

But you can see why tradition sorts “The Travelling Grave” into horror—the Grave feels less like a robot than a monster. The point of a robot is that you understand how it works, or at least know it works in a way that’s understandable. It’s programmed, directed. The Grave is more ambiguous. Munt talks like it consciously stalks its prey, but it has a safety-catch and in other moments behaves like a passive booby-trap. How self-directed is that crabwise glide?

Monsters and ghosts have this same ambiguity; their motives are opaque, their intelligence unclear. Could you talk to a Xenomorph if you knew its language, if it has a language? Does Sadako have free will or is she a magical VHS computer virus? Is the bedsheet ghost from “Oh, Whistle and I’ll Come to You” someone or something? The Grave feels like it might fall on the “someone” side; it feels angry.

5.

“The Travelling Grave” jump cuts straight from Munt’s admission that he collects coffins to the party standing around a Grave unpacked and introduced to Valentine in the section break. The group is in mid-conversation. Hartley’s reticent—he tells only as much as we need and trusts us to keep up, to a degree striking in an era where genre fiction errs on the side of over-explanation. But it’s also how transitions work in dreams—you’re in one place one moment, in another the next, context already understood. From here the dream-tone increases. This key to why “The Travelling Grave” fits into a book of ghost stories: it’s proto-SF, but tonally irrational.

Munt plans to welcome the soon-to-arrive Hugh with a game of hide-and-seek. The dream-tone ramps up as the lights go out. Valentine hides in a lidded bath, which he soon realizes is not a bath—Hartley doesn’t tell us what it is; he doesn’t need to—and overhears Munt planning to “test” the Grave when Hugh arrives. Hugh still has not reappeared but in his absence his narrative function has reversed: not only is he not the hero, he’s the damsel in distress.

More sudden shifts: Munt assures Bettisher the Grave’s safety-catch is on, but when Bettisher leaves Munt turns abruptly, titteringly irrational, “chanting to himself in a high voice.” Munt seems to appear and disappear. Valentine, alarmed for Hugh, seems to teleport right to the spot Munt has hidden the Grave.

Up to now Munt has been as identified with silence as with death. (Also as in a dream, it feels like things aren’t making noise when they really ought to—a pretty impressive achievement in text.) He first appears “on silent feet and laughing soundlessly.” His chauffeur, now picking Hugh up at the station, is equally soundless and seems an extension of the car. Valentine is also silent as he carries the Grave to a more out-of-the way bedroom, like picking up the Grave also meant picking up Munt’s narrative role. He’s relieved to make noise again once he sets the Grave down. (Is it really a footstool he trips over on the way out?)

6.

Hugh is greeted by a dark house and an absurd game. The spectacle of grown men playing hide-and-seek should be the funny kind of absurdity. Somehow it isn’t. Valentine thinks up a fatuous excuse to leave, repeating it to himself until it’s “meaningless, even its absurdity disappeared.” Munt vanishes. The rest of the party are left to navigate a country house party without their host, which again should be farcical but leaves everyone uneasy.

All this is leading up to the moment Hugh makes a funny discovery in his room. He reassures Valentine it’s really funny, “not funny in the sinister sense.” This will not last. It’s a pair of shoes upside-down on the parquet floor, seemingly stuck.

Hugh is slow on the uptake and still knows nothing of the Grave, so it’s (again) ironic that he’s the first one to realize the truth, his dialog sliding seamlessly from jocular to hysterical as the penny drops: these shoes are worn by a pair of feet sticking out from between the parquet. For reasons Hugh cannot imagine his host has been crushed and embedded in the floor, a grotesque death and a humiliatingly silly one. Munt is a grim joke, both really and sinisterly funny. Valentine has plucked Death’s sting by rendering him ridiculous.

But we were asking what makes this a ghost story, and still haven’t fully exhumed the body under the floorboards.

7.

When you come to a story written in another time, contexts obvious to the original readers can be invisible to you. Stories don’t say things that go without saying.

Let’s go back to the moment when Hugh thinks “they can’t kill me,” a habit he’d at one point suspended: “With the war, this saving reservation had to be dropped: they could kill him, that was what they were there for. But now that peace was here the little mental amulet once more diffused its healing properties…” But should it?

When Valentine arrives at Munt’s he gazes through the window and remarks “How lovely everything looks.” The wind immediately blows the smell of burning garbage in his face. I keep coming back to tone: “The Travelling Grave” is ironic. Paul Fussell might find that appropriate. In his The Great War and Modern Memory Fussell identifies irony as the characteristic tone of postwar literature. Heck, Fussell argues World War I itself made irony one of the twentieth century’s dominant moods: “I am saying that there seems to be one dominating form of modern understanding; that it is essentially ironic; and that it originates largely in the application of mind and memory to the events of the Great War.”

When “The Travelling Grave” was first published, in Cynthia Asquith’s 1929 anthology Shudders, the Great War had been over for just ten years. In the entire story, the “they can’t kill me” paragraph is the only time the war is overtly mentioned. But it’s everywhere under the surface. A country house visit is described like an extension of the carnage requiring a “violent mental readjustment … the fanciful might call it a little death.” The house is “pierced” by windows—an odd choice of words unless you’re calling up violent imagery—and hide-and-seek is “mimic warfare.”

And the Grave itself is a thoroughly modern killing machine. The lasting cultural memory of WWI is that it was a modern war, specializing in mechanized mass-produced death. The most indelible image of the war (accurate or not) is one of old-fashioned generals marching waves of infantry into machine gun fire to be mown down factory-style. Armies developed new weapons and defenses—chemical gas, gas-masks. WWI was the first war in which tanks were used and the Grave is like a tiny tank. To contemporary readers the Grave would have been a killing machine with specific contemporary associations, the way cold war audiences got a particular kind of vibes from anything nuclear.

“The Travelling Grave” feels haunted not because there’s a haunt in the story but because the story is itself haunted by an almost unmentioned war. They could kill Hugh; that’s what they were there for. But he shouldn’t have stopped worrying with the armistice. They can still kill him, or anyone who stumbles into the wrong room in the wrong country house. “The Travelling Grave” is a story about how the war permanently broke this now fatally absurd and meaningless world. Death is a mechanism that may strike you down at random if you don’t have someone looking out for you, someone who may not even know what he’s doing but at least has a sense of the absurd. The man most fit to deal with this weird postwar existence is not a conventional English gentleman but a fool.