(Continued from Part 1; read the linked post first!)

Part One of this post was a couple weeks ago, so I thought I’d start by repeating the list of stories that got both Hugo and Nebula nominations in 1974:

- Michael Bishop, “Death and Designation Among the Asadi”: An ethnographer living among ostensibly uncivilized aliens goes bonkers. (Worlds of If, January-February 1973)

- Michael Bishop, “The White Otters of Childhood”: Thousands of years from now, the remnants of humanity are relegated to an island on an earth ruled by advanced posthumans and de-evolved morlocks. But the really relevant Wells story is The Island of Dr. Moreau. (The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, July 1973)

- Gardner Dozois, “Chains of the Sea”: The aliens have landed. One boy discovers they’re not here to talk to us. (Chains of the Sea)

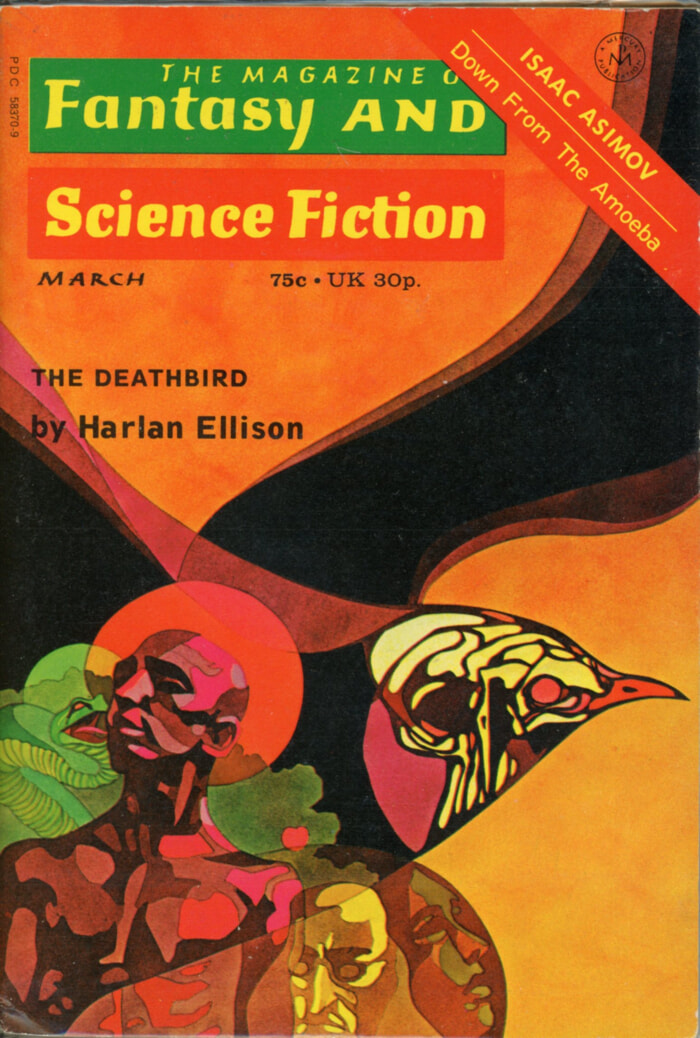

- Harlan Ellison, “The Deathbird” (Won the Hugo for Best Novelette): Adam—you know the one—reincarnates to turn out the lights on a dying earth. (The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, March 1973)

- George R. R. Martin, “With Morning Comes Mistfall”: On an alien world, a scientist makes a discovery. Everyone feels mildly let down. (Analog, May 1973)

- Vonda N. McIntyre, “Wings”: On another alien world, a temple guardian takes in an injured youth. They don’t get along. (The Alien Condition)

- Vonda N. McIntyre, “Of Mist, and Grass, and Sand” (Won the Nebula for Best Novelette): A post-apocalyptic healer treating a patient from another culture loses her best snake. (Analog, October 1973)

- James Tiptree, Jr., “The Girl Who Was Plugged In” (Won the Hugo for Best Novella): In a future where all advertising is product-placement on reality television, an outcast teenager remote-controls the body of a corporation’s perfect artificial celebrity. (New Dimensions 3)

- James Tiptree, Jr., “Love Is the Plan the Plan Is Death” (Won the Nebula for Best Short Story): An alien would like to have sex without dying afterwards, thanks. (The Alien Condition)

- Gene Wolfe, “The Death of Doctor Island” (Won the Nebula for Best Novella): A talking island provides dubious psychiatric care. (Universe 3)

And bear with me while I repeat a paragraph on one of our continuing threads:

Again, from Rieder’s Colonialism and the Emergence of Science Fiction: early anthropologists saw societies they studied as more distant in time than space—they were different stages of human development, living examples of the past.

Pest Control

Up next is Gardner Dozois’ “Chains of the Sea,” a good old fashioned The War of the Worlds invasion. Wells’ novel was famously an exercise in role-reversal, turning the British Empire back on itself and asking “what if people temporally ‘ahead’ of us”—Wells’ Martians were giant heads with vestigal bodies, which Wells imagined might be our own ultimate evolutionary destiny—“treated us the way we treat people ‘behind’ us?”

What Dozois adds is to juxtapose the invasion with the kind of relentlessly bleak kitchen-sink drama that would get Ken Loach saying “I dunno, man, this seems a bit much.” Then, having already made this move in the previous year’s “A Kingdom by the Sea,” Dozois adds a third strand. We share Earth with ancient incorporeal beings, implied to be what we once thought of as spirits or fairies—they used to have “covenants” with humans, now forgotten. But the new neighbors are ready to negotiate.

Dozois recounts the invasion with zoomed-out journalistic omniscience, wryly emphasizing the impotence of governments who rush about ineffectually and fail to impress even their own citizens. The aliens don’t care about us; we’re brushed aside when necessary, otherwise ignored. In the years after World War 2 aliens tangled with competent, level-headed government scientists and military officers. Sci-fi movies were the SF equivalents of police procedurals, The Lineup or He Walked By Night with giant ants. Post-Vietnam, “Chains of the Sea” is less impressed.

In between we get claustrophobic close third person sections in the head of Tommy, a child beaten by his abusive father and despised by his teachers. Tommy is one of the rare humans who can speak to spirits, who he calls “Thants.” In another time he might have been a seer or a mystic. In early 70s small-town America he’s a truant and troublemaker fobbed off on a resentful school psychiatrist who seems disappointed when his patient turns out not to be on drugs.

The invasion fails to impinge much on Tommy’s misery, but parallels it. The first line sets the tone: “One day the aliens landed, just as everyone always said they would.” Which sounds subtly childish, like a kid who knows of course he’s getting detention, why expect different? Every adult in Tommy’s life is described with the physical grotesquery of a bug-eyed monster. Probes and drones emerge from the alien spacecraft; people watching on the scene swear they took half an hour but clocks confirm it was less than five minutes. Tommy, anticipating humiliation at the hands of his teachers, wonders how his classmates move so fast. He realizes he himself is “stiffening up, becoming dense and heavy and slow.”

“Chains” casts the entire adult world as rotten, predatory. The old eat their young. A corporation plugs Philadelphia Burke into a machine and discards her when she burns out (“The Girl Who Was Plugged In”), Dr. Island chews Nicholas up and spits him out (“The Death of Dr. Island”), America ships a generation of young draftees off to Vietnam. Tommy, having no apparent value as material, is just a nuisance.

Tommy tells his schoolmates a story about a dragon in the sea, hunted by a warship, who escapes by turning to stone. No way, says one kid, the ship would have killed it. Tommy realizes he’s right: there was nowhere to escape to, the dragon couldn’t leave the sea. There is nothing outside his world to escape to.

Meanwhile humans are becoming a “nuisance” to the Thants, and they and the aliens agree it’s time for some pest control. Tommy’s Thant contact is sorry but not very sorry. “You are a hobby we have been much concerned with,” he says, and Tommy realizes the one being he considered a friend never thought of him as a person.

What’s interesting is how the aliens plan to clear us out: they’re going to increase entropy. Literally, this is a scientific term related to the second law of thermodynamics describing the unusable heat energy in a closed system. What’s relevant here is its use as metaphor: we use the word entropy for everyday human-scale decay. The aliens are killing us with our own incompetence, pushing us to fall apart faster, “winding down the world.”

Otters

Michael Bishop’s “The White Otters of Childhood” takes us from The War of the Worlds to The Island of Dr. Moreau: our narrator, Markcrier Rains, has read the novel and has a father-in-law named Prendick. But the setup feels like The Time Machine. In the far future humanity shares an island chain with Morlockish sub-humans. Earth is ruled by the Parfects, posthumans ahead of us on the old-school anthropological timeline; Markcrier is humanity’s occasional ambassador. As in “Chains of the Sea” we sense the Parfects are adults to our children, though less threateningly. They don’t resent us, they’re disappointed. Markcrier confesses his visits bore him, like a kid stuck at an elderly aunt’s house listening to the grownups talk through Cousin Bill’s messy divorce.

Markcrier returns from the Parfects to learn the human ruler, Fearing Serenos, has raped his wife. She soon dies in childbirth. I said in part one that Bishop, still inexperienced, makes the occasional false move in these stories. The big one is that both include some not especially tasteful form of fridging. But compare Markcrier’s formal, funereal apologia with Egan Chaney’s decreasingly hinged monologues—again, Bishop’s at least mastered voice.

Plotting revenge, Markcrier and Prendick use their social status to separate Serenos from his goons and convince the islanders he’s died a natural death. The reality is wilder. Prendick knows how to surgically devolve humans into animals. He’s succeeded where Dr. Moreau failed because it’s easier to animalize humans than the other way around—easier, Markcrier observes, to destroy human souls than to build them. (Entropy will get you every time.) Markcrier and Prendick will painfully, humiliatingly convert Serenos into a shark.

Their vengeance is an awkward anticlimax. Serenos pitifully sinks to the ocean floor. Markcrier wonders what the hell he even wanted. As though this were all a test, a Parfect appears with a message: They’ve been “delaying an inevitable decision,” but now it’s time to choose whether standard-issue humans will be allowed to live, or put to sleep. Again, the superior nonhumans plan to clean us up like termites—but “Otters” isn’t sure they aren’t in the right. Markcrier resolves to become a shark himself. Humans are an “evolutionary mistake,” predators playing at personhood. “I am convinced that we are the freaks of the universe; we were never meant to be.” Are we not men? Apparently not.

Everything Must Go

Harlan Ellison begins “The Deathbird” as he began “Repent, Harlequin, Said the Ticktockman,” with a preemptive strike in a fight no one actually tried to pick. He’s the hip cool Robin Williams teacher, we’re the class too square to get where he’s at. “This is a test,” he says, launching into a page of impatient “hints” for an audience who can’t be trusted not to misread him.

The story proper begins on a dying Earth in the furthest possible future, circled by a “Deathbird.” A snakish alien, Dira, brings Nathan Stack out of suspended animation. Flash back millions of years: Dira learns Earth has been awarded to a vaguely adversarial patriarch. Dira’s people, Earth’s creators, are sticking him with the job of staying behind to observe. He can expect to be slandered. It’s obvious what’s going on here, despite which Ellison follows up with a chunk of Genesis and some dictatorially leading reading group questions.

Tempting as it is to feel insulted, the metafiction is strategic. If “The Deathbird” is a mosaic, the keystone of the story’s arc can be something outside the story: “Abuhu,” an autobiographical sketch memorializing Ellison’s real-life dog. When Abuhu grows old and sick the vet tells Ellison it’s time to put him to sleep. Ellison uses the needle himself. The last thing he wants is for his beloved dog to be put down by a stranger.

Dira leads Nathan through a blasted hellscape towards a mountain, past hostile plants and surly predators. Nathan recalls past lives, including one where his dying mother begged and bribed him to inject her with morphine, to help her die quickly instead of over agonizing hours. Dira explains Nathan has reincarnated many times, and in his original life he was Adam. Yes, that one.

To skip forward a moment, “The Deathbird” ends with the dedication “THIS IS FOR MARK TWAIN.” Which might bemuse anyone whose mental model of Twain involves picket fences and riverboats, but Twain was weirder than his popular image. As he aged Twain increasingly turned to fantasy, often biblical, often unfinished and unpublished. The Twain who influenced Ellison was arguably his cultural contemporary: Letters From the Earth had been published in 1962, barely more than a decade earlier. This was a volume of unpublished Twain miscellanea his estate long thought too embarrassing to print. In the title story Satan, exiled to Earth instead of Hell, writes to his fellow angels telling them to get a load of the crazy things humans believe about God. Basically, Twain is doing CinemaSins on the Bible. He wrote “Letters” to amuse himself and with no real consistency; sometimes the Bible is a collection of humanocentric myths, but then there’s a sequence where Noah’s Ark was a real event and Satan is dishing the gossip that didn’t make it into print. Sometimes Satan is our moral superior, sometimes he’s ironically blasé about the thing Twain is really angry about. One weird and lengthy passage earnestly argues women can have more sex than men and therefore should be allowed to marry entire harems of husbands. It’s not the best thing in the book (“Fenimore Cooper’s Literary Offenses” is funnier, and the unfinished “The Great Dark” more disconcerting). But it’s the part that might appeal to someone, like Ellison, who values edginess.

It’s also notable that Dira is an alien, not an angel. Ellison’s Biblical apocalyptic fantasy is couched in science fictional terms. Not through technobabble—Ellison world-builds with prose. The earth Dira descends through is described geologically: diatomaceous earth, monoclines and synclines. Nathan Stack’s crypt is “smooth and reflective”—tech words, not tomb words. Which is significant in two ways. First, at this point there’s still not much fantasy in the Hugos and Nebulas, and what there is rarely makes both shortlists. (Fantasy is more likely to show up on the Nebula lists.) Second, for all I dig at Ellison—his literary persona is one hundred percent buffoon—when he’s on his game he’s one of the best stylists in the genre; to this day few SFF writers can touch him.

Anyway. At the top of the mountain is God, owner of Earth, representative of human society; and he is old, mad, and senescent. Earth itself is irreparably worn out. Humanity has spent itself to spiritual bankruptcy. There’s nothing left to do but shut off the lights. This is why Dira woke Adam: it’s time to put Earth out of its misery. As the last human, it’s Adam’s responsibility to call the Deathbird. Dira is kinder than the Thants or the Parfects: we’re being put down again, but at least he’s not leaving us with strangers.

Not that he’s leaving us with anything else. Earth was a bad seed and a rotten undertaking and there’s nothing to be done but chuck it all in the bin. Which, honestly, is a fitting cap to the science fiction of 1974. At best, “The Girl Who Was Plugged In,” “With Morning Comes Mistfall,” and “The Death of Doctor Island” give us futures with nothing to look forward to. Civilization ruins everything in its power; authority is an omnipotent, omniscient god using and discarding young people like Kleenex. More often we’re no better than animals (“The White Otters of Childhood,” “Death and Designation Among the Asadi,” “Love is the Plan the Plan is Death,” those apes in “With Morning Comes Mistfall”), destined to be put down like rabid dogs (“Otters” again, “Chains of the Sea,” “The Deathbird”).

Science fiction in 1974 no longer thinks humanity is competent to build a decent world. It’s questioning whether civilization can, or even should, survive. But this isn’t an apocalypse or a dramatic Ragnarok, just a quiet shot of morphine. The world is winding down, growing cold, quieting. (The Deathbird simply enfolds the Earth in its wings; its cry is a gentle “sigh of loss.”) Shrinking back into the caves.

But there’s one writer we haven’t yet covered.

…Or Maybe We’re Overreacting, Here

“Wings” is not the best story to introduce Vonda N. McIntyre. It’s very slight and looks slighter next to “Of Mist, and Grass, and Sand.” I’m not sure why fans in 1974 remembered it, let alone nominated it twice.

It does, though, fit our pattern. On a poisoned, dying planet of avian aliens an ailing oracular shrine-keeper rescues a youth with a broken wing. Everyone else has fled into space. The youth is certain no one is left and thinks it’s time to shut the world down Deathbird-style; otherwise “the world would kill our children, or the children would kill the world again.” The keeper, last representative of society, protests. He tries a divination to find other survivors… but if anybody anywhere might be carrying on, he can’t find them. Sorry, kid.

The keeper is also a threat. These aliens pick their gender upon adulthood. The youth is at about the right age and the keeper, a lonely widower, is tempted to pressure the youth into making a choice, fantasizing they might replace his dead wife. This would for obvious reasons be a crime, and he’s holding himself back. But it feels like this kid’s in danger of getting used and abused by their elders just like Tiptree’s P. Burke, Wolfe’s Nicholas, and Dozois’ Tommy.

But for the first time the danger is averted: the youth leaves unharmed. Later he becomes a man and, out of pity, returns to care for the dying keeper. And he has news: he’s found other survivors, and they plan to rebuild. The old man’s world is ending. But a world continues to exist outside his point of view, beyond what he could imagine.

“Of Mist, and Grass, and Sand” is the good McIntyre story. It won a Nebula and would later become the first chapter of her best-known novel, Dreamsnake, which scored both a Hugo and a Nebula itself. The plot is simple: Snake is a doctor who packs her little black bag with actual snakes, including a rare and difficult-to-breed dreamsnake whose bite is an anesthetic. She’s stopped to heal a young desert nomad with a tumor. She earns the trust of her patient and a young man asked to assist her, but doesn’t talk much with his parents. When she leaves her dreamsnake with the kid they panic and kill it. Snake blames herself.

Let’s jump forward seven years to Thomas M. Disch’s book review column in the February 1981 issue of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction. I’ll talk more about this column in a future post—it was significant enough at the time to get cover billing—but briefly Disch thought science fiction at the end of the 1970s was pandering and overly facile, favoring high concept Hollywood pitches over complexity. His chief target was a group of writers he called “the Labor Day Group,” one of whom was McIntyre. What’s relevant here is that Disch identified “Of Mist” as one of these stories where “the interest of the work should be telegraphable in one sentence,” in this case “What if snakes were beneficent instead of poisonous?” Which—because Disch was a brilliant writer but an unreliable critic—completely misses the point: he’s reading the snakes literally when he should read them metaphorically.

This is another story where a low-tech culture bumps up against a high-tech one. Snake is a big-city medical student bringing newfangled medicine into the backwoods. Like the teleological anthropologists we keep coming back to, she sees the nomads as the past—backwards, not worth talking to. She talks to her patient, but not to the parents; as the story begins it occurs to her they may have thought her mute. A Campbellian story might have blamed her snake’s death on ignorance and superstition, the desert-dwellers killing it because they aren’t far above the animal level themselves. But in this story the death is Snake’s responsibility.

Snake heals with snakes, is named Snake, because most readers will have a visceral revulsion for snakes. If the nomads shrank back from the gleaming antiseptic gadgetry Dr. Crusher wields on Star Trek we’d sneer: get a load of these hicks! Swap the gadgets out for snakes and we get their fear on an emotional level. It’s easy to identify with Snake; McIntyre also wants us to identify with the nomads.

“Of Mist, and Grass, and Sand” rejects the teleological model of civilization and the condescension that comes with it; Snake’s fault was not meeting these people as equals. Snake didn’t explain herself to them, didn’t respect their intelligence or their fears, because she didn’t think of them as her contemporaries. In a 1993 interview in Science Fiction Chronicle (later reprinted in a memorial booklet online) McIntyre said, “I’d describe what I’m doing as observing characters who have great differences but mostly manage to get along without forcing each other to conform, and without killing each other.” It’s striking that of all the double-nominated stories of 1974, only McIntyre’s see this as a possibility.

People are developing new medical techniques and sharing them. The world is starting to function again, and Snake is learning how to communicate. The fundamental message of the SF of 1974 is that we’re screwed. “Of Mist,” though, presents a world where… well, this is a nuclear[1] post-apocalypse. so we’re still screwed. But there’s something on the other side of screwed.

Omelas

Here I want to consider a story technically outside this project. In 1974 Ursula K. Le Guin’s “The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas” (published in New Dimensions 3, alongside “The Girl Who Was Plugged In”) snagged a Hugo nomination, and won, but didn’t get a Nebula nod. Which is surprising. Of all the stories here it’s the best remembered, and the only one writers still write response stories to. Bad response stories. Because even though it’s the most popular and well-remembered SFF story of its era, it’s a story few SFF fans understand.

Le Guin opens by describing Omelas in the midst of their Festival of Summer. Long story short, it’s nice. Le Guin guesses we’re looking for the catch—a king? Slavery? No, she insists, this actually is a good place. And Le Guin stresses the Omelans aren’t naïfs, because she knows we think of happiness as “something rather stupid.” She wishes she could convince us.

Fantasy worlds are rhetorical devices. Most fantasies’ rhetorical projects call for worlds with a certain solidity; they ask us, for the sake of the story, to entertain the conceit that Middle-Earth, or Westeros, or Earthsea could have an independent existence. So it’s easy to miss that Le Guin has a different agenda, signaled when she suggests “Perhaps it would be best if you imagined it as your own fancy bids”—because no utopia suits everyone, but also because Omelas isn’t fixed.

Le Guin wonders what kind of technology Omelas has—she doesn’t know, is the thing. Le Guin likes trains, but, hey, decide for yourself. If you think Omelas needs orgies, add one. Is there religion? Maybe yes, but not organized. Recreational drugs? No, but, on second thought, yes. Le Guin is worldbuilding and world-remodeling in front of us. This is a thought experiment. Omelas is not real even within the context of the story.

Now Le Guin asks a question: “Do you believe?” It occurs to her a lot of readers won’t. That’s when she introduces the kid in the closet. She outlines their miseries, describes how the Omelans learn about the child and learn to rationalize it. “Now do you believe in them?” she asks.

This is often read as a trolley problem. But this can’t be the actual point. Le Guin is an enormously intelligent and subtle writer, and as philosophical problems go this is approximately on the level of a dorm room bull session.[2] What if you could make a whole civilization happy by torturing, like, one person? Would that be worth it? Makes you think. The whole scenario feels carefully constructed to look carelessly tossed-off. Le Guin doesn’t bother to suggest in what way torturing this kid might guarantee Omelas’ greatness and, inasmuch as “Omelas” is in dialog with a genre that prides itself on worldbuilding, this feels less like surrealism than contempt. It’s not worth working out the details. Fine, says Le Guin. Here’s your dark secret. Enjoy. Happy now?

Here’s what nobody mentions about “The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas”: it’s a work of deeply impatient, magisterial sarcasm. In remembering Le Guin fandom often casts her as a staid, stately philosopher. But if you’ve read her essays you know she had a wicked line in snark.

Some, says Le Guin, walk away from Omelas. Here’s where the response stories get confused. Literal worldbuilding is a box SFF fans can’t imagine their way out of. They imagine Omelas having the same relation to its story that Middle Earth has to The Lord of the Rings. In this reading literal people are literally leaving a literal place; therefore, “Omelas” must be making the (fundamentally libertarian) argument that the best response to injustice is to opt out of anything that doesn’t live up to your personal moral code.

So stories “solve” Omelas, imagining the leavers as refugees struggling with their decisions or arguing, no, the correct thing to do is stay and fight.[3] All of which is about as cogent as watching The Muppet Movie and complaining, waitaminute, frogs don’t talk… because, again, louder this time, Omelas is not a literal place. This is not literal walking. The ones who walk away from Omelas are leaving an idea. Le Guin is challenging us to imagine a society can exist that does not depend on somebody getting locked in a closet.

(It may be relevant that “Omelas” was written during the cold war. Capitalists and communists alike believed they had the key to utopia, but to reach it they had to crush their internal enemies—reds on one side, kulaks or bourgeoise on the other.)

“Omelas” is not demanding reflexive positivity. Le Guin wrote plenty of dystopian stories and the next year when she wrote about a utopia it would be an ambiguous one. “Omelas” is criticizing cynicism. The assumption that better things aren’t possible, that goodness is naïve and happiness rather stupid. That optimism and utopianism are always a retreat into cozy falsehoods, and cynicism always sophisticated, courageous.

In the introduction to “Omelas” in The Wind’s Twelve Quarters Le Guin quotes William James:

All the higher, more penetrating ideals are revolutionary. They present themselves far less in the guise of effects of past experience than in that of probable causes of future experience, factors to which the environment and the lessons it has so far taught us must learn to bend.

Le Guin wants us to imagine futures where we teach the environment to bend. There’s a lesson here for SFF specifically: it should be capable of imagining utopias. Not because we will ever arrive at one. Society, like a house or a car, needs constant maintenance to avoid slipping into injustice; our victories are not self-sustaining. Civilization is constant work. But we can’t do the work without imagining what we might be working for.

The End of Imagination

It feels like science fiction in 1974 had reached the end of imagination. The stories that struck a chord with fans were stories where humans were savage apes alternately disregarding and preying on each other, destined for a long slow painful decline. The old ate their young. Human civilization was a failed experiment; time to put it out of its misery. We’re just screwed, okay?

It sounds like I’m judging, here, but I really can’t. There’s a long history of people turning to eschatology when times are… not necessarily hard, but confusing. If SF fans were looking for eschatology in their entertainment, hey, that’s healthier than starting a millennial cult. Art is for working out feelings, not uplift or instruction, and maybe this burst of nihilism felt cathartic. On the other hand…

We’ve circled back several times to the old-school anthropologists’ timeline of civilization, in which the history of civilization is teleological; it has levels, like a ladder or a Dungeons and Dragons character, and less “advanced” societies are exemplars of our own past. Eventually civilization will reach its final form: utopia. Omelas without the closet kid. This is what Francis Fukuyama meant by “The End of History”—he thought in liberal democracy humanity had discovered the ultimate, ideal, stable political system.

It’s tempting for science fiction to treat history teleologically; projecting technological progress into the future is its key technique. Golden Age SF imagined we’d reach utopia through science. John Campbell thought science fiction itself was world-changing. Exploring the changes wrought by new technologies is a major component of golden age SF and the entire substance of some stories. Later, the New Wave was aligned in sympathy and aesthetics with the youth movements of the sixties who sometimes fought but more often just vibed really hard for social progress.

But by the seventies both these utopias seemed mirages; neither science nor social movements could end the war, heal the planet or balk Nixon. Hell, science mostly seemed to invent new bombs and new ways to poison rivers. As for vibes, well, Kurt Vonnegut said it best:

During the Vietnam War, which lasted longer than any war we’ve ever been in—and which we lost—every respectable artist in this country was against the war. It was like a laser beam. We were all aimed in the same direction. The power of this weapon turns out to be that of a custard pie dropped from a stepladder six feet high.

Most who think of history as a ladder (pie optional) imagine their society at the top rung; at least, the top is a society they can imagine as an extension of themselves. On the face of it you’d think seventies science fiction’s assumption of screwedness is pushing back on that. But the certainty that we’re screwed also assumes history is teleological. It just thinks the arrow of history points down.

We were meant to be the top of the ladder, or at least be able to see the top of the ladder. Utopia is always recognizably us; we are always the end of history. But waiting for science to solve our problems hadn’t worked, and neither had protesting, and we were all out of ideas. So… maybe instead of teleology, we should have been thinking about eschatology? If the next step wasn’t utopia, it had to be armageddon. If not us, nothing. The assumption that apres nous, le deluge; that we must literally be the end of history; that, our revolution having failed, nothing else can succeed is just another face of exactly the same arrogance that had colonial anthropologists—and a lot of Golden Age SF—assuming their own society was the future and the foreign cultures they encountered were the past.

It’s easier to imagine destroying this world than to imagine new ways of fixing what we can with the tools at our disposal, let alone building something newer and weirder, and in 1974 science fiction’s imagination had run out.

Most of the stories I’ve covered here feel less like they’re looking forwards, more like they’re closing off an era. Not just because so many literally close off any future; “Asadi” deals with a deliberately old-fashioned kind of archaeology, “Mistfall” is working in a tradition of Kiplingesque colonial space opera, and “Otters” calls back to H. G. Wells.

But then there’s the story we covered way back at the beginning of part one, “The Girl Who Was Plugged In.” It’s eerily relevant to our 21st century media landscape. And it’s a clear heir to the New Wave—the prose has urgency and bite, feeling alive in a sea of elegies—while pointing forward to cyberpunk, a genre that doesn’t yet even exist. In retrospect, “Girl” is a major signpost on the path to SF’s future.

So, in a subtler way, is “Of Mist, and Grass, and Sand.” Partly because it points towards an era in which SF would increasingly subvert or reject Golden Age SF’s treatment of science as teleological and civilizations as temporally unequal (The nomads aren’t primitives Snake needs to teach, they’re contemporaries she needs to explain herself to). But also just because it suggests humans have a future, and will continue to have a future even if our particular society doesn’t manage to avoid blowing itself up. We ended, but we’re not the end; even if it isn’t an extension of us there is always something on the other side of screwed.

Even if it doesn’t feel good, even if we think we’re powerless and The System is rigged, it’s not our place to throw up our hands, declare everything over, and insist it’s time to turn out the lights. It’s our job, with whatever tools we have, to arrange our world in a way that makes it easier and not harder to build the world that is to come. The work begins with the willingness to imagine any world coming after us at all.

-

It’s not clear here what happened, but in Dreamsnake Snake travels past radioactive craters. ↩

-

The trolley problem aspect wasn’t the real point when Dostoevsky used this scenario, either. ↩

-

What does it say about the present moment that the 2025 Nebula-winning Omelas response solves the torture problem by killing… um, the torture victim? ↩