Sometimes, as I browse the internet, an article or a blog post syncs up eerily with a book I’m reading. Most recently it was a post by Doctor Science at Obsidian Wings, who created “the John Donne Test”:

At some point in there I came up with what I’ll call the John Donne Test, because he said “Any man’s death diminishes me.” The Test is very simple:

Is there a second murder? (a second incident; two people murdered at once doesn’t count)

If the answer is “Yes”: you fail.

If it’s a mystery story without any murder, you get an A.

There’s nothing wrong with telling stories about murders. These are, after all, fictional people. But, argues Doctor Science, there’s something squalid about stories that don’t treat death as a tragedy–that casually kill characters off merely to raise the stakes, push the story along. Which is not only a problem in mystery stories. (And is, maybe, another example of a tendency I’ve noticed for some stories to treat background characters as literally less important than protagonists.)

I like mysteries but I’ll admit it’s odd the genre is so murder-centric. It’s not like there’s no potential for drama in fraud or embezzlement or a good old-fashioned jewel heist. And Dorothy Sayers’s Gaudy Night, possibly the greatest mystery novel of the “Golden Age,” is murderless. But sometime between Arthur Conan Doyle and Agatha Christie the genre decided murders were the only proper subject for detective novels.

Speaking of Agatha Christie, early 20th century mystery novels are comfort reading for a lot of people, me included.[1] Which is a bit weird, and I don’t think it’s necessarily a criticism or condemnation of the genre to acknowledge that. Lots of good things are a bit weird. Mulling over and poking at the weirdness of things, even things you love, can be fun.

Mysteries aren’t the only genre built around grim subject matter. There’s horror, and grimdark fantasy, and dystopian science fiction. But those are genres people go to when they want to be in some way unsettled, whether that means being kept in suspense, being made to think about difficult subjects, or just having their heads enjoyably messed with. (The thing I like about horror movies isn’t the horror, exactly; it’s the surrealism.) The audience is having fun, yes, but it’s fun discomfort. No one talks about “cozy horror” or “cozy dystopias.”[2] But there are “cozy mysteries.”

As to what kind of comfort can be found here… well, it’s a cliché and a truism that the detective novel offers a restoration of order, the rebuilding of a community thrown into turmoil and uncertainty. But in this case I think the truism is, well, true. For myself, given the failures of America’s justice system–the false convictions, the police departments that function as racist protection rackets–imagining some quixotic amateur swooping in to sort out its mistakes is a satisfying wish fulfillment fantasy. (Granted, usually the problem in real life isn’t that prosecuters missed some vital clue, but that they faked forensic evidence; or ignored exculpatory evidence; or, alternately, deliberately let a killer off the hook because he happened to have a badge. Sherlock and Elementary notwithstanding, a modern Sherlock Holmes’s greatest challenge would be less explaining the facts and more shaming the authorities into doing the right thing.)

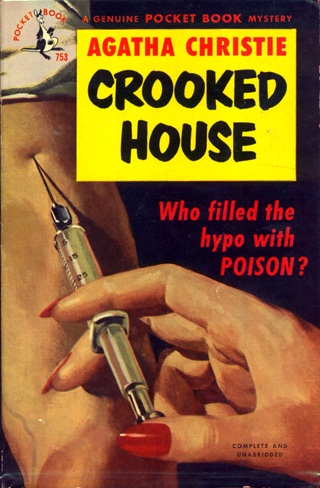

When I came across the Donne Test I was reading Agatha Christie’s Crooked House. Christie’s books are synonymous with the cozy mystery. But Christie herself was less cozy than we remember. As I reread her work in recent years I noticed many of her novels are shrouded in a pall of unease never entirely removed by the neat solution. Christie’s most famous novels, remember, include (Spoilers!) The One Where Everybody Dies, The One Where Everybody’s Guilty, and The One Where the Killer is Your Pal, the Narrator. Some of the Miss Marple novels in particular are practically noir.[3] For all that Christie’s books were the kind of mysteries Raymond Chandler hated, I suspect if Philip Marlowe met Miss Marple they’d exchange knowing nods, each recognizing a kindred spirit who’d also Seen Too Much. Crooked House is another unsettling novel, particularly considered in light of the Donne Test. Christie considered it one of her favorites, which is interesting because here she seems to cast a jaundiced eye over her own literary career.

Crooked House doesn’t star any of Christie’s recurring characters but looks like a typical Christie. The title is taken from a nursery rhyme. The narrator is a statistically average bland detective novel love interest.[4] The ending might be considered a twist in that the killer (who I will soon reveal) is a character most mysteries wouldn’t normally lump in with the suspects. And the grasp of proper police procedures on display here is sketchy. The elderly head of a household has been murdered, apparently by his much younger wife. Narrator Charles Hayward is both the fiancé of the old man’s heir and the son of the Scotland Yard commissioner in charge of the case, which is totally convenient and not a conflict of interest at all.

Charles, naturally, does the amateur detective thing, snooping around and interrogating the family. And at one point he finds himself using the phrase “the fun will start,” and thinks to himself:

What extraordinary things one said! The fun! Why must I choose that particular word?

Well, there’s your question. Charles isn’t the only one having fun. His fiancé’s young sister, 12-year-old Josephine, loves detective stories. She’s been spying on everyone, collecting secrets and writing them down in her notebook, and she knows how this situation is supposed to go:

“I should say it’s about time for the next murder, wouldn’t you?”

“What do you mean—the next murder?”

“Well, in books there’s always a second murder about now. Someone who knows something is bumped off before they can tell what they know.”

And, sure enough, someone unsuccessfully tries to kill Josephine, and later successfully poisons her nanny. And Josephine knew it was coming because she arranged it herself. She killed her grandfather, for entirely childish reasons. Then she sets up her own death trap because she’s read a million detective novels and now, as a newly-fledged author, she knows it’s time to raise the stakes. And she adds another successful murder to make things more exciting, because the nanny’s just a background character, right? You can just kill background characters off. You know, for effect.

It’s impossible not to read Crooked House as Agatha Christie interrogating her own formula, complicating the entertainment we get from her novels, owning their weirdness. It’s a reminder that detective novels fail when they forget murders are tragedies as well as puzzles. At the end Josephine’s dying great-aunt deliberately wrecks her car with Josephine in it and it’s as though Christie is trying to symbolically dispose of the temptation to focus so thoroughly on the puzzle that the people disappear.

Christie was particularly proud of Crooked House; she wrote an introduction explaining that she saved the idea up for years and worked on it extra-carefully. The people who adapt her novels into films and TV shows have not similarly embraced it. According to Crooked House’s Wikipedia page, this is one of only five unfilmed Christie novels–a movie was planned a few years ago, but so far hasn’t gotten off the ground. Maybe they’re afraid the audience would walk away feeling a bit ghoulish.

-

Christie’s not my favorite; Dorothy Sayers, Edmund Crispin, and Margery Allingham are all more lively. ↩

-

Although I’d argue they exist… think of all the dystopias designed expressly to get knocked down by Very Special teenagers. Or the old Universal horror movies where the monsters were lovable and charismatic and the heroes always got away safe in the end. ↩

-

For instance, speaking of the Donne Test, A Pocketful of Rye includes what may be the saddest and most unfair secondary murder of any Christie novel. ↩

-

Characters weren’t Christie’s strong suit–she wrote types. This is why Miss Marple is such a great detective–her criminological methodology is entirely about recognizing types which, as a Christie protagonist, she’s surrounded by. ↩