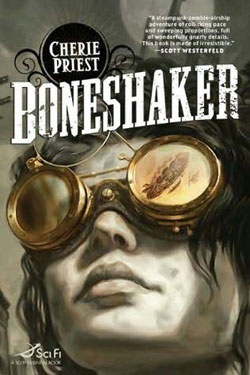

Last year, the SF blogosphere was so excited about Cherie Priest’s Boneshaker you would have thought it had caused actual bones to be shaken. I suspect massive name recognition was a major reason this novel ended up on both the Hugo and Nebula shortlists, because Boneshaker does not aspire or pretend to be anything more than a light, breezy adventure novel–the kind of book that meets the baseline standard of “entertaining” but isn’t meant to step beyond into “exciting” or “compelling.” This is a good and worthwhile thing for a book to be… but it’s not unusual.

From the Nebula or Hugo shortlist, I expect something ambitious, or moving, or thoughtful, or beautiful. Something significant, memorable, and mind-blowing. A book that a reasonably well-read person might honestly judge to be among the five or six best SF novels published in the past year. I am, in other words, in Adam Roberts’s camp on the whole Hugo Awards deal.

Yes, I know. The fact that Cory Doctorow and John Scalzi were nominated for Little Brother and Zoe’s Tale, neither of which rose to Boneshaker’s level of craft–or that Robert J. Sawyer and Jack McDevitt have ever been nominated at all, for anything–should have squashed my illusions. Still, I cannot extinguish the small ember of hope that whispers maybe, this year, the nominators followed some criteria more stringent than “What are people talking about on the internet?”

The problem with this, I’d argue, is not so much that it’s unfair to other, more ambitious SF novels that go unrecognized. They’re big books and can take care of themselves. What’s worse is the vast disservice it does to books like Boneshaker.

A reader’s experience of a book depends partly on the assumptions they bring to it. It’s like James Thurber’s story “The Macbeth Murder Mystery”: Pick up Macbeth thinking it’s a detective story, and you’ll read it wrong. Anyone who reads Moby-Dick like a C. S. Forester novel will be bored and annoyed and will miss all the really good bits, and you can say the same for a reader who comes across the Horatio Hornblower stories while looking for another book like Moby-Dick. Or a reader who reads a light adventure novel expecting an award nominee. I read Boneshaker because it made the Hugo and Nebula shortlists, and was left without much patience for a book I might otherwise have enjoyed. When the Nebula judges saddled Boneshaker with a nomination, they guaranteed that a large chunk of its potential audience would come to it with the wrong expectations.

So, ignoring the nominations… how good is Boneshaker at being what it actually tries to be? Here I have to admit that, with different expectations, I would still have been… not necessarily the wrong reader for this book, but not the ideal reader. I’ll overlook a lot if a book pushes my buttons; I cut Boneshaker less slack because the buttons it pushes belong to other people. One reason Boneshaker got so much attention was that it managed to incorporate two current internet fads: it’s a steampunk novel about a city overrun by zombies. Steampunk I can take or leave. Zombies are boring, and I absolutely cannot wait for SF fans to get over their fascination with the things. The zombies are not Boneshaker’s main focus, so I can’t say they bothered me, but I wasn’t excited to see them, either.

So when I say I thought Boneshaker wasn’t as fast-paced and breezy as I’d like, that it in fact seemed drawn out far too long… well, it’s a relative judgement. One of Kage Baker’s Company novels, Mendoza in Hollywood, is a couple hundred pages of time travelers just sort of hanging out in 19th-century California, followed by a slight trace of plot. I couldn’t put it down. I like spending time with Baker’s characters and her world, even when her characters have so much downtime they spend an entire chapter watching a movie. If you like spending time with zombies and steampunk gadgets, maybe you’ll want as much Boneshaker as you can get.

Me, though… I thought the novel would have been stronger if it had been cut in half. And there’s a specific half that’s disposable. Boneshaker is split between the points of view of Briar Wilkes, the widow of the man whose pulp-villain-style drilling machine loosed a plague of zombies on Seattle, and her son Zeke, who kicks things off by sneaking into the now-walled city to find traces of his dad. Of the two leads, only Briar is interesting.

Zeke’s only function in this story is to be rescued, and his rescue would have been more suspenseful if we’d had no more idea than Briar of what had become of him. Instead, we spend every other chapter watching Zeke bounce from character to character and fail to accomplish anything. Whenever Boneshaker switches to Zeke’s point of view, the story starts running in place. Typical of Zeke’s half of the book is a chapter in which he’s put on a dirigible leaving the city; it turns out to have been stolen, the original owners show up to retrieve it, and Zeke runs away. Neither dirigible crew appears in the novel again, and the incident has absolutely no effect on anything. It’s just a teaser for another novel in the same universe.

Briar is smart and resourceful and drives the plot. Boneshaker is really entirely her story–it’s about getting her life unstuck and into a place where she can talk about her past and move on. The escaping-from-zombies bits might go on a bit too long for my taste, but Briar’s chapters have all the excitement missing from Zeke’s. A sign of the skill and craft behind this book, and the thing that most impressed me, was one of the climactic revelations–without saying too much, one of Boneshaker’s central mysteries is a question of identity; Cherie Priest’s answer seems superficially anticlimactic but is actually far more interesting than the alternative, and it sets up a bigger revelation at the end of the book.

So am I recommending Boneshaker, or not? I guess I’d recommend half of it, to steampunk fans. Fortunately, it’s easy to read just Briar’s half: the chapters are prefaced with engravings of a pair of steampunk goggles or a dirigible, depending on whether they’re Zeke’s chapters or Briar’s–and Zeke’s chapters don’t drive the plot, so the novel is perfectly comprehensible without them!