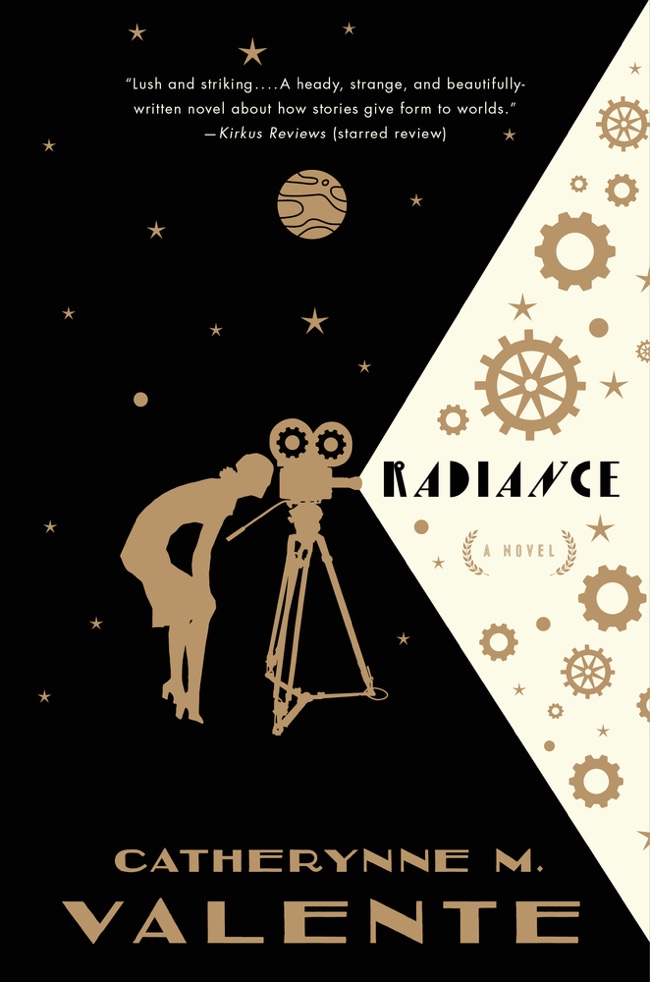

I read Radiance last year and took some notes towards a blog post but never wrote it. I came across the file and decided to correct that. This post will be vaguer it might have been if I’d come to it while the book was fresh in my mind, but this was one of the best books I read in 2016 and I wanted to register my approval. (It’s an expansion of Catherynne M. Valente’s short story “The Radiant Car Thy Sparrows Drew,” which is online if you want to see whether Radiance is your kind of thing.)

Radiance views common SF tropes–multiverses, transhumanism, alien ecology–through the lens of the planetary romances written back when people still thought Mars might have canals. In the early 20th century humans, with help from the milk of the alien Callowhales, are living and making movies on Venus and Mars and the Moon. Black and white and silent movies, mostly, because the Edison company has the patent on color and sound.

Percival Unck directs fantasies and melodramas. His daughter Severin directs documentaries. Up until she disappears mysteriously while investigating the mysterious disappearance of a small colonial town on Venus. Percival can think of no better way to deal with his grief and uncertainty than to plan a movie about his daughter’s vanishing, one that might find a solution.

Catherynne M. Valente writes some of the best prose in contemporary SF. Radiance really lets her show off. It’s a documentary/assemblage novel, which is both a great worldbuilding device and an excuse to play with voice. There are scripts, and transcripts, and letters, and diaries, and news articles. And Percival Unck’s movie treatment, which changes style as he revises its genre from film noir to pulp space opera to a musical comedy gather-the-suspects-in-the-drawing-room finale. I knew this would be one of my favorite novels of the year when the mind-blowing, space-and-time bending answer to its central mystery was revealed by a vaudeville tune sung by a Callowhale.

Radiance is full of detectives, real and fictional. Sometimes both at once. At one point an actress famous for playing a sleuth finds herself doing real detective work, and the investigations of Anchises St. John, sole survivor of the lost colony, are fictionalized in Unck’s film treatment. It’s not always clear what’s real and what’s filtered through someone’s story.

People often make sense of their lives using narrative as an organizing principle. They turn life into stories. Which sometimes works and sometimes doesn’t, because reality is different from stories in crucial ways. For one thing, stories end. Most important questions have final, settled answers. Stories tie off all the loose ends in a way that’s emotionally satisfying; reality keeps unraveling more.

Moving from fact to fiction and back is how Percival ties up loose ends. He keeps a filmed diary and has no compunctions about re-staging his life to best effect. When Severin’s mother left her on his doorstep as a baby, Percival had his assistant carry her back out into the rain so he could dramatically restage her unexpected arrival. For Percival, that Severin is missing is in some ways worse than if she had died: it’s open-ended, questions forever unanswered. His film treatment changes styles because for Percival the key to solving Severin’s disappearance is figuring out its genre.

Severin turned to documentaries in reaction to Percival’s fictions, but she arranges her storylines, too, in her own way. She doesn’t restage her life… but when her expedition arrives on Venus and finds Anchises dazed and wandering the empty village, she puts off trying to talk to him until her crew has set up the lighting. As Severin’s former lover puts it, Percival “lived through things first and then reshot them to get them right, while she hung back until everything was perfect, then called action. Couldn’t live through a thing until the camera was rolling.” Documentaries aspire to objectivity, but it’s important to remember they’re also narratives, arguments building to possibly illusory conclusions.

Unlike a story, reality, barring the actual heat death of the universe, doesn’t actually end. That’s the anxiety-inducing thing about real life. But in the end I think Radiance suggests that maybe it’s also the good part.

On another, disconnected note… In a recent post on Philip K. Dick I wrote that my favorite thing about his writing is the prolifgacy of his imagination, the way he would just throw stuff into his novels. Radiance doesn’t resemble Dick’s work at all, but it’s equally generous with wild ideas. Valente gives us a nineteenth-century solar system, and an alternate history of the movies, and a spooky cosmic mystery, and the next step in human evolution, and the many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics, and a glorious patchwork of styles, formates, and genres, and… and I’m sure some people–

And yes, I know I’m setting up a straw man here, but it’s a straw man I’ve observed in the wild–

I’m sure there are people who would ask why we need all of this. Could you have a novel that explored endings, and disappearances, and filmmaking, and storytelling as a straightforward narrative? Or a conventional space opera? Or without the SF angle at all, setting it in the days of silent film?

Of course, the answer is, yes, you could, but it wouldn’t be this novel, one that explores those themes in this specific, individual way. And this novel is excellent. And it’s excellent partly because so many big concepts were generously, and confidently, stuffed into one novel. In that it reminds me of another favorite from the last couple of years, Jo Walton’s The Just City and its sequels, which combine Greek gods and social SF and time travel and robots and philosophical tangents and constantly refuse to take their plots in the direction you’d expect.

Sometimes I pick up a SF novel that’s had good buzz centered on a couple of high-concept ideas. Then I discover those ideas are all they have, the rest of the novel being filled in with default tropes, stock plots, and a voice that doesn’t distinguish itself from its neighbors on the shelf. It can be a little frustrating. It’s not that I don’t understand the comfort to be found in a slightly new but still familiar story. I often need comfort reading myself. (Especially lately!) But I already know how to find those books; it’s harder to find SF that surprises me. I need more novels like Radiance that are not cautious variations on other stories, but instead have the self-confidence to be inimitably themselves.