(I’ve been reading the stories that got both Hugo and Nebula nominations. To see all the posts in the series, check the “Joint SFF Nominations” tag.

Because this one was running long, I decided to split it into two parts.)

As the sixties grind to a halt, I’ve noticed SFF take a pessimistic turn. That’s not changing in this installment. The question I try to ask about each batch of stories is what recurring themes do I see? This year I’m noticing two: the first is possession. People are changing bodies or losing their free will. The second is decay. Teenage barbarians roam a nuclear wasteland. A galactic empire collapses as aliens attack the human mind. People on a spaceship forget the outside universe. A fantasy world loses its magic. Earth, long past its prime, succumbs to an alien invasion. In at least two stories, America is just gone. Everything’s falling apart in:

1970

The novels nominated for both the Hugo and Nebula in 1970 were Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Left Hand of Darkness, Norman Spinrad’s Bug Jack Barron, Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five, and Robert Silverberg’s Up the Line. The Left Hand of Darkness won both the Hugo and the Nebula, deservedly; it’s a classic, as is Slaughterhouse-Five. I haven’t read the other two.

The stories nominated for both awards were:

- Gregory Benford, “Deeper Than the Darkness”: A space crew rescuing the survivors of an alien attack discovers the aliens might have a more subtle weapon than they’d assumed.

- Samuel R. Delany, “Time Considered as a Helix of Semi-Precious Stones” (Won the Nebula for Best Novelette and the Hugo for Best Short Story): A thief visits Earth to sell some stolen goods.

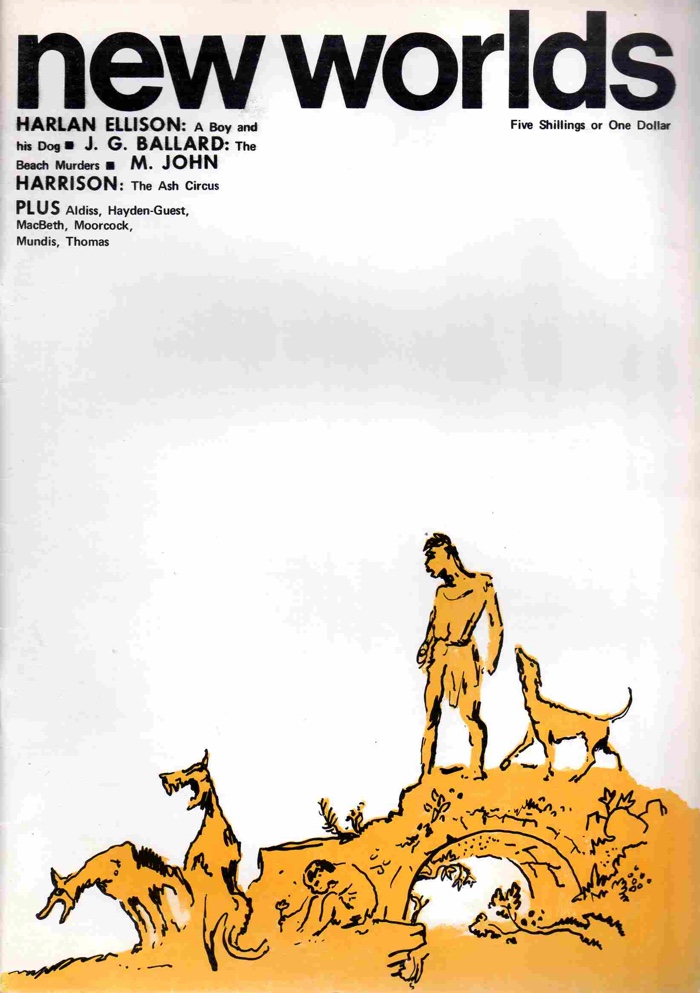

- Harlan Ellison, “A Boy and His Dog” (Won the Nebula for Best Novella): A feral teenager and his smarter dog scrape by in a post-apocalyptic wasteland.

- Fritz Leiber, “Ship of Shadows” (Won the Hugo for Best Novella): A nearsighted man living on a spaceship meets a talking cat, acquires a pair of glasses, and runs afoul of vampires.

- Anne McCaffrey, “Dramatic Mission”: A sentient spaceship ferries a troupe of actors to an alien planet.

- Larry Niven, “Not Long Before the End”: A warlock confronts the sex pest barbarian who’s been hassling his wife and reveals an appalling secret.

- Robert Silverberg, “Passengers” (Won the Nebula for Best Short Story): The challenges of dating in a world where people are routinely possessed by incorporeal alien pranksters.

- Robert Silverberg, “To Jorslem”: The guy from 1969’s “Nightwings” travels to Jerusalem as a pilgrim, hoping to recover his youth.

Which is the best story in this batch? Take a wild guess.

Yep, it’s Samuel R. Delany again, with “Time Considered as a Helix of Semi-Precious Stones.” It’s not the only good story here—I also recommend “Deeper Than the Darkness,” “Ship of Shadows,” and “To Jorslem.” But as usual Delany is working at another level of density and complexity. It’s also a thematic outlier. Most of these stories are preoccupied with a couple of themes. Most absorbed a downbeat flavor from the violent, volatile years when they were written; if civilization hasn’t fallen apart, it’s having a hard time holding itself together. “Time Considered” is less pessimistic, more philosophical, and feels less of its time. It could be published as new today.

The narrator is a professional thief and master of disguise. He changes identities like clothes, keeping only the initials H.C.E. (In other stories from 1970 we’ll see people change bodies, or find their minds changed for them.) H.C.E. begins by telling us his age, but not straightforwardly: “Lay ordinate and abscissa on the century. Now cut me a quadrant. Third quadrant if you please. I was born in ’fifty. Here it’s ’seventy-five.” He’s describing his life as a segment of his century, connecting himself to his context.

H.C.E. returns to Earth to unload his loot. He’s warned off by Maud, who knows an underworld password: the name of a semiprecious stone that can mean different things depending on how and when it’s spoken. She’s a surprisingly friendly envoy from “Special Services,” who predict the movements of criminals. She explains Special Services practices “hologramic information storage,” analogous to the way any fragment of a hologram contains the entire image. Special Services estimates where H.C.E. will be by taking every piece of information they have about him and relating it to his entire life and circumstances. Maud is letting him know because “Information is only meaningful when shared.”

Later, at a party, H.C.E. hears “if everything, everything were known, statistical estimates would be unnecessary. The science of probability gives mathematical expression to our ignorance, not to our wisdom.” The speaker is a Singer. Singers closely observe the world and describe it in extemporaneous poetry and song. It’s illegal to reproduce the Singers’ words; you experience a Singer’s work once, in person.

In his 1964 book Understanding Media Marshall McLuhan argued a medium’s content was less important than the properties of the medium itself: how people relate to different media, what kinds of thought they encourage. In “Time Considered” the Singer tradition developed because “While Tri-D and radio and newstapes disperse information all over the worlds, they also spread a sense of alienation from first-hand experience.” The Singers counterbalance mass media; the point is their immediacy. They relate information back to the world, turning raw data into meaning.

One common fan mode of reading, especially among fans of big franchises like Star Wars and Marvel, is data collection. Fans amass wikiloads of trivia describing every corner of a fictional universe, hunt down backstories for every extra who crosses the screen. They look for continuity errors and “plot holes” and write stories to “fix” them. They want to know everything but don’t think about what it means. What “Time Considered” is doing—

Well, one thing it’s doing, because like all good fiction “Time Considered” is complex and not reducible to a single theme, and I’m not trying to know everything, just looking at one piece of the hologram—

“Time Considered” is arguing for a different kind of reading where lists of facts aren’t ends in themselves but part of a pattern of meaning. By the end of the story H.C.E. can predict how his relationship with a criminal rival will develop, seeing not only the immediate conflict but past it into a future partnership. He’s learning to read information holographically.

“Time Considered” is an outlier among 1970’s nominees because, like the other Delany stories I’ve covered, it shows affection for people. Every character is allowed dignity and a point of view; Delany seems to genuinely like each one. His work feels benevolent. In a Delany story things don’t go right for everyone—that’s the nature of stories—but the worlds he creates aren’t hopeless.

This won’t be true for most of the other stories.

Another Story it’s Not True For

To maximize the whiplash, let’s consider “A Boy and His Dog.” If you’ve read other posts in this series you’ll have gathered that I find Harlan Ellison ridiculous—he’s the kind of guy a teenager thinks is cool but an adult recognizes as a buffoon—but still love his writing… usually. I’m not a fan of “A Boy and His Dog.” This is the first time I’ve ever made it all the way through this story (though I did know the twist ending).

The reason I hate “A Boy and His Dog” may not be the reason you’d assume. Many SFF fans have strict moral standards for protagonists. The idea is that the main character is there for the reader to identify with, an example to aspire to. If a protagonist does a thing the author must think it’s a good thing to do. This is, of course, completely wrong. A protagonist is not necessarily there for the reader to project themselves onto. A fictional character is a rhetorical device, part of the argument or exploration of ideas that is the story. Sometimes what that argument needs is an asshole. A protagonist doesn’t have to be good, only interesting.

So I don’t have a problem with awful protagonists, which is good because Vic is awful. Blood, his dog, is also awful. All the other characters we meet are awful as well. They live in a post-apocalyptic America that is, you guessed it, awful, except for the underground bunker Vic encounters which is awful in a different way. The problem is that none of this awfulness adds up to anything interesting, or original, or even coherent.

It’s a well-known story that’s had comic book and movie adaptations so you may know the plot. Teenage Vic wanders the wastelands of post-war America with his dog Blood. Blood is intelligent and telepathic, bred by the military; at one point Vic watches a film in which dogs napalm a village. Blood raised Vic and taught him to read. This arrangement seems common. Other boys have other dogs and, like Vic, they were raised to be the kind of people who would napalm a village.

So Vic comes across a young woman, Quilla June. This is the point where I bailed on the story way back when I first tried to read it, because Vic plans to rape her. Because, yes, 1970 has two more stories featuring horrible sex. (At least this batch of stories doesn’t have any incest, which is not a sentence I thought I would need to write before I started this project, but here we are.) Quilla June whacks Vic over the head and leaves, but not before dropping enough clues to let him follow her into her underground bunker. The bunker is set up like a Mayberryesque small town. All the men are sterile and Quilla June lured Vic down to be a sperm donor. On further reflection she’s bored with the whole deal, so she shoots some people and the pair make their way back up. Blood, who stayed on the surface, is injured and needs something to eat, like, right now. A boy loves his dog, so…

“A Boy and His Dog” is comprehensive in its disgust for humanity. The young people on the surface are barbarians, the old people underground are fascists. This story argues civilization is a paper-thin veneer; every American is one disaster away from unleashing the monster just under their skin. Which, fair enough, might have seemed plausible under Richard Nixon, but it’s too much. In the last years of his life, Ellison said in an interview:

“I used history as my model for the condition of the country in ‘A Boy And His Dog,’ where, after a decimating war, like the Wars Of The Roses, for instance, the things that become most valuable are weapons, food, and women. Women were traded and treated like chattel. I tried to make it clear in the stories and the novel that I found this distasteful, but it’s the reality of what humanity’s like when it’s gone through this kind of apocalyptic inconvenience, if you will.”

The Wars of the Roses were also the model for A Game of Thrones, prototype of modern grimdark fantasy. “A Boy and His Dog” has a similar appeal. If you expect the worst from other people that must mean you’re not as bad, right? And it makes you feel smart: you’re seeing the world as it really is, man.

Is it, though? Most apocalyptic fiction assumes after the bomb drops we’ll have to fight off gangs of punk-style barbarians (these days they’re usually zombies). But in real-world disasters people are as likely to pull together as take potshots at their neighbors. Why did this world go for the latter option over the former? “A Boy and His Dog” doesn’t seem to realize the question needs an answer. It’s just assumed that the world after the bomb drops is a world without compassion.

Quilla June is the only important character in the story after Vic and Blood. Even granted that we’re seeing her through Vic’s eyes, he doesn’t understand her, and she spends much of the story manipulating him, she’s weirdly erratic. One moment she vomits because Vic bopped her father on the head, the next she’s gleefully mowing down her neighbors with a rifle. She spends the first half of the story playing Vic like a penny whistle, but at the end suddenly has no idea how to handle him. That the story’s third most important character is a randomly bouncing plot device gives you some idea of how much thought Ellison put into working out anybody’s psychology here. Ellison is angry, and at his best his anger can be incisive, cutting. In “A Boy and His Dog,” it’s just mindless.

(To be continued in Part 2, with more decay and stories of possession.)

1 thought on “The Venn Diagram of Science Fiction and Fantasy Awards: 1970, Part One”