1.

I often wish more fantasy novels would focus on ordinary lives. Literature in general is not about adventure, but about… well, life. What it means to be a person in the world, even (especially) an ordinary person who is not going to save it.

And then Travis Baldree’s Legends and Lattes came along. And I said, “No, not like that.”

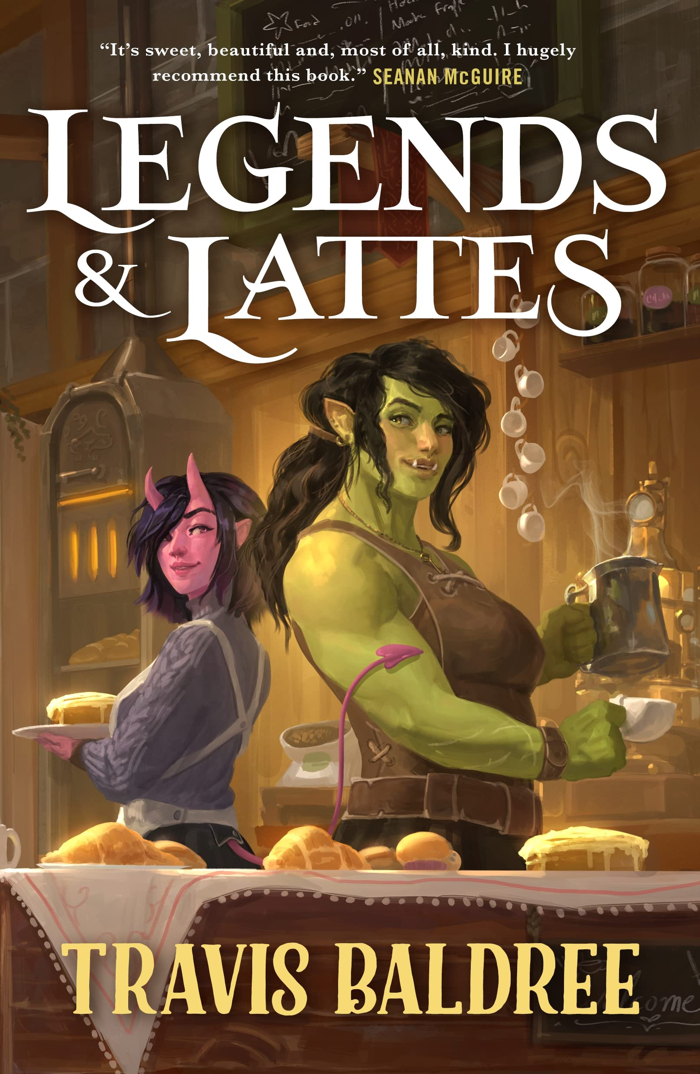

I tried Legends and Lattes because it’s gotten buzz as a popular self-published book that got picked up by Tor. I finished it merely because it was so insubstantial finishing was as easy as quitting. This book has nothing to say. It feels like the work of an author unfamiliar with the idea novels can be more than descriptions of things happening. It is innocent of theme or subtext. (Well, not entirely innocent; there’s that “the real treasure is friendship” business beloved of children’s cartoons. But this is as close to the surface as a theme can be. And what kind of friendships are we talking about? We’ll get to that.)

2.

What Legends and Lattes describes happening is the opening of a coffee shop in a generic fantasy world. Viv, the protagonist and proprietor, is an orc who’s abandoned Dungeons & Dragons adventuring for peaceful entrepreneurship. Her business attracts a found family of employees, contractors, and customers. These include a succubus, a rat guy, and a legally distinct pseudo-hobbit. Legends and Lattes is a diverse book in terms of D&D races. If any of the human characters were nonwhite I don’t recall, but it does teach us not to stereotype succubi or gnomes.

Even sans theme this might have been logistically interesting: how does a coffee shop work in a world where “adventuring” is a career? How do you establish a business in a fantasy city? How do you rebuild a livery stable into a restaurant? How does an orc make coffee? Where does an orc get coffee? Alas, where the answers to these questions are not easy Legends and Lattes handwaves them. Most of the detail is decision-making, a series of brainstorms as Viv and friends invent the familiar amenities of a 21st century American coffee shop—iced coffee! Biscotti! Live music! Travel mugs! But what specific carpentry is needed to transform a stable into a shop? Well, Viv’s Hob friend handles that. How does the oven work in a city with no electricity or gas? That’s the rat chef’s business. How does Viv make coffee? A vaguely described machine does it. Both machine and coffee are delivered by an improbably reliable postal service for a low-tech, monster-strewn world. With shipping this convenient, it’s hard to believe no one but Viv has heard of coffee.

Tonally, the book feels like Terry Pratchett minus anything as unruly as jokes. Moments feel like they should be jokes, like when Viv, the orc living in a D&D world, posts a want ad including language like “food service experience desired,” “advancement opportunities,” and “wages commensurate.” But there’s no sense the book realizes this might be funny. It just assumes this is what want ads say the multiverse over.

As a tale of found family, the tone the book aims for is “heartwarming,” but it begs to be loved with such earnest seriousness it lands on “smarmy.” And something about the family Viv finds feels false: Her family includes employees, contractors, and customers, but not neighbors or coreligionists or people she meets through hobbies. Viv doesn’t have friends whose relation to her is not transactional. They’re the ones with the actual skills that make her business work while she organizes them. This is a workplace family, and Viv is the heart of the family because she’s everybody else’s manager.

3.

Fans of Legends and Lattes call it cozy. We’ve all heard of cozy mysteries. Ask aficionados and they’ll tell you their attributes include an amateur detective, a small, close-knit community (a subculture, or a country house, or a literal small town), and a lack of sex, violence, or profanity. These remove… let’s say literary turbulence—features that make readers anxious. Amateur detectives are fun to identify with; they don’t have to follow annoying rules and don’t work for a corrupt carceral system. Close-knit communities feel insulated; troubling social issues seem distant if they come up at all. Draw a veil over the awe and terror of violence and the mystery becomes pure puzzle. And you also don’t have to read the word “shit.” If the appeal of mysteries is the restoration of order after trauma, the appeal of a cozy mystery is that you never feel trauma in the first place. What’s interesting is that cozies descend from and style themselves after “golden age” mysteries, but golden age mysteries were not cozies. Writers like Christie and Sayers were often out to trouble the reader.

Similarly, Legends and Lattes descends from the fantasy works that inspired Dungeons & Dragons, but without the mixed emotions and scary bits that are part of what made Tolkien, Lieber, or Moorcock memorable. Instead, this is genre as warm fuzzy blanket. Unlike almost everything else in this review, this is not a criticism; there’s a place for fuzzy blanket books. I just don’t think there’s any reason they can’t have ambitions along some other axis, even as they build a cozily familiar world.

Familiarity is definitely part of the coziness here. A world like a D&D game feels comfortably homey to a lot of geek-culture readers. Even many of us who’ve never played actual D&D have spent time with Baldur’s Gate, not to mention D&D-adjacent games like Dragon Age and Skyrim. Elfy-dwarfy stuff feels like visiting the old neighborhood. And, like Baldur’s Gate and Dragon Age, where the world doesn’t need to be medieval or fantastical it feels contemporary. The characters are modern Americans in spirit, the better to identify with. (That’s important in a game!) Pratchett does this too, but where the Discworld books mixed modernisms and fantasy clichés with satiric intent Legends and Lattes is just worldbuilding by default. Pratchett was interested in how societies work and had serious criticisms about the ways in which they don’t. Legends and Lattes puts a fantasy filter on an idealized version of middle-class America, like a D&D Hallmark movie.

Even here, I’m not complaining. You could do something with this! It’s just that Legends and Lattes isn’t doing anything with this.

The real problems come in when you notice what parts of the world are left out—and, to return to a previous theme, what parts of the logistics of coffee.

4.

A lot of books have worldbuilding which is technically, from a strictly logical perspective, bad. This is not a problem. Worldbuilding is part of how a story communicates its themes. If part of the world is effective theme-scaffolding it doesn’t need to make literal sense. I mean, Kafka’s good, right? And it’s not like he’s the most realistic world builder ever. (You’re a bug? How did that happen?)

But when a book has nothing going on but pedantic descriptions of the decision-making surrounding D&D world’s first coffee shop, I start wondering about the internal logic. And my biggest question is: how does this city work?

Seriously, who runs the place? Is there a city council? A monarch? We never learn what kind of government it has. Someone is maintaining kerosene streetlights and cleaning the streets. The water is clean. Sewage is taken away. The postal service implies safe and well-maintained roads, and a system to find addresses. We don’t know who or what runs any of this. A late disaster gives a brief glimpse of emergency services, but the book depicts them less as people and more as weather. There’s no sense the infrastructure of this society is maintained by anyone—it’s just there, like a natural resource.

What’s particularly striking is what Viv doesn’t need to do to build her business. She doesn’t need a business license; alternately, assuming a more medieval setup, she doesn’t need to join a merchant’s guild. No one makes sure she’s following building standards as she remodels. Her coffee shop doesn’t need to pass health inspections. No rules, whether laws or guild regulations, govern how she treats her employees. She doesn’t pay taxes. Opening a business is as simple as buying a building, remodeling, and hanging a sign.

The problem is the local crime boss, a woman named Madrigal who runs a protection racket. If Viv doesn’t pay a sizable monthly tribute something unpleasant will happen to her business or her employees. Exactly what isn’t specified; as organized crime goes, this is pretty G-rated. But everybody warns Viv Madrigal is serious. People who refuse to pay have regretted it.

Viv consults her old adventuring troupe. Paying is out of the question, but does she want to fight? Again, it’s interesting to see what isn’t suggested: nobody suggests going to a police department, city watch, or government agency of any kind. An American might assume the local police-equivalents are murderously corrupt and racist, but that’s not the problem. It’s also not that they can’t touch Madrigal, or that they only help the rich. They just don’t exist. Laws do not come up as a concept. It doesn’t occur to Viv or her friends that this city might have laws to protect its citizens’ rights, or provide recourse if they’re broken. The idea is outside their frame of reference.

It also doesn’t occur to anyone to band together with other victimized businesses and present a united front. Anyway, that would lead to all-out war, and Viv doesn’t want to pull her old sword down from the wall. The point of opening a shop was to stop being a person who waves swords around. Viv’s got her self-image to think of. Fighting Madrigal would eliminate a threat, but also eliminate Viv’s ability to regard herself as flawlessly moral.

So Viv cuts a deal with Madrigal, who turns out to be a nice old lady who will leave Viv alone in return for regular deliveries of cinnamon rolls. (I told you, this mob is really G-rated.) Just like that, Madrigal is part of the family and Viv is defending her: “some people might consider any of her crew to be assholes, just because of the nature of the business. But I don’t think that way… I’ve got respect for people who have to get their hands dirty to get things done. That’s just work.”

The only moral distinction Legends and Lattes makes is between nice people and “assholes.” You can run a protection racket and not be an asshole. You can smash up some hapless merchant’s shop or beat up his employees and not be an asshole. That’s just another job, like running a coffee shop. An asshole is someone who creates problems specifically for Viv or her friends, and can’t be bought off with cinnamon rolls. Madrigal is still soaking the other small business owners in town, or destroying their livelihoods, but Viv is okay and I guess that’s all we’re supposed to care about. Solidarity? Viv doesn’t know those people and doesn’t owe them anything.

What makes Legends and Lattes cozy, the reason it’s low-stress, is that the world does not make demands on its heroine. Viv has no obligations to anyone outside her chosen family. A found family is a refuge with both the power and the right to close the door on humanity and pull the ladder up after it.

Legends and Lattes has nothing to say. Unfortunately, that’s not the same thing as saying nothing. What it’s saying is a bit like something Margaret Thatcher once said: “there is no such thing as society. There are individual men and women, and there are families.” As long as that includes found families, I think Legends and Lattes would agree with Margaret.

i love this review, i kept getting this book recommended to me and i love reading people complain about bad books!

You should try Dungeon Meshi. It’s a manga about adventurers cooking and eating monsters in a dungeon and I feel like it executes the themes attempted here a lot better.

This was an excellent read. The quote at the end hit hard.

Thank you for this review. I saw nothing but hype for it, read it, and was left very disappointed. Your review perfectly encapsulates why

Stumbled across this review because I felt the same way about L&L and was shocked that no-one seemed to agree. This is a really well-written piece, and perfectly encapsulated everything that bugged me about this book. It’s so weirdly… libertarian? I don’t know about you, but that’s not my idea of a comforting world.

One small thing, they do actually suggest going to the police (or the town guard, or whatever), but dismiss this idea (in a single line of dialogue!) because they are all controlled by the Madrigal’s gang. And no-one even suggests that this might be a bad thing. There’s also a line where one of the Madrigal’s lackeys compares extortion to taxes, and neither the characters nor the narrative itself offer any pushback against this idea.

A deeply weird book.