For the last few months I’ve let my blog lay silent, as happens from time to time. I had covid in December of last year and the time I spent resting put the brakes on my momentum. My attention span also hasn’t been great, so it’s taken me this long to return to blogging.

To get started again I plan to finish a few reviews I took notes towards months ago. This is one of them.

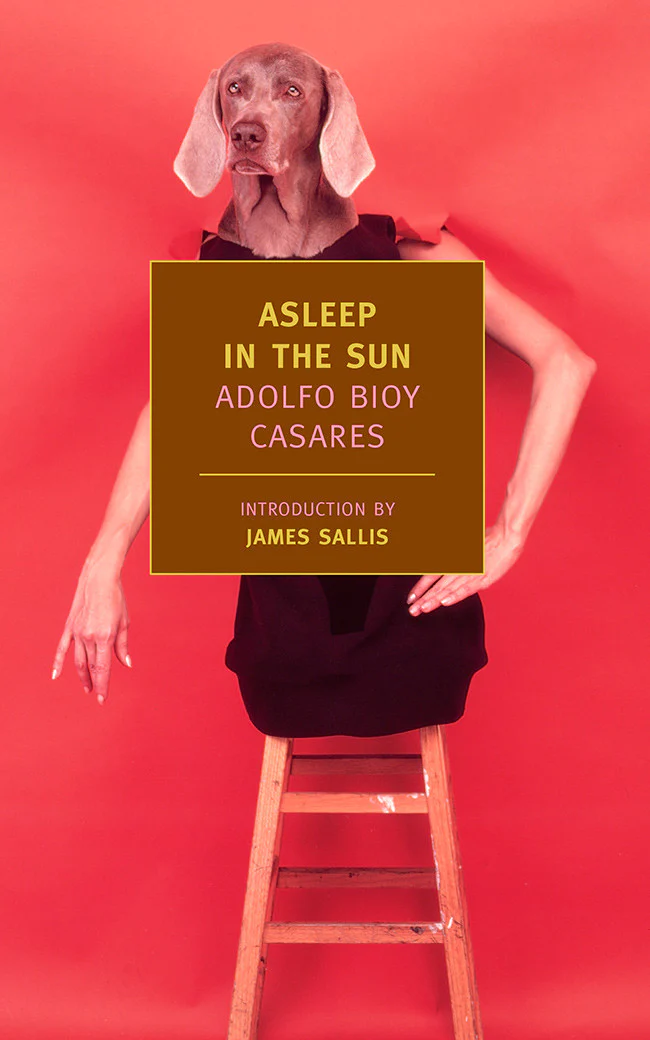

Asleep in the Sun is the last Adolfo Bioy Casares book readily available in English I’d yet to read. (There are more, but they’re out of print. Someday I’ll hunt down secondhand copies.) Bioy Casares was a friend and colleague of Jorge Luis Borges, the husband of Silvina Ocampo, and the author of The Invention of Morel, which I’m convinced is one of the most significant yet undervalued science fiction novels of the 1940s. Asleep in the Sun doesn’t reach those heights, but it’s good.

Bioy Casares benefitted from a publishing environment that didn’t categorize books too rigidly. The novel starts as a domestic comedy only to turn into a science fiction story about a mad scientist in what feels like an abrupt swerve. But the SF plot is there from the beginning, unrecognized by the narrator. Bioy Casares has a talent for laying unnoticed threads, then pulling them together into an unexpected plot.

(Spoilers follow. As with Morel, this is a book where you might want your first reading to surprise you.)

Our narrator is Lucio Bordenave. It’s way too easy to talk Lucio into things against his better judgement. He works at a bank but repairs clocks as a side hustle. If the foreman of the Lorenzutti factory wants Lucio to repair the factory clock he may say “I wouldn’t take it for a hundred dollars,” but he’ll wind up working on it.

And when his wife Diana’s friend, a dog trainer, insists she’s unstable and needs a stay in the local mental hospital Lucio senses this is a bad idea, but Diana’s gone before he knows it. And he goes along when her physically identical (but temperamentally different) sister moves in, and when the trainer presents him with a dog coincidentally named Diana. Two Diana-substitutes. Despite their good qualities neither is adequate.

Diana is the one thing Lucio is firm on: he loves her unreservedly, though she treats Lucio with contempt and causes no end of trouble—recently her attempts to “help” Lucio got him fired from his job at the bank. This relationship doesn’t seem good for Lucio, but that’s his call. The thing is, Diana isn’t mentally ill—just touchy and temperamental and unhappy. She is, in short, difficult. That’s what bothers Dr. Samaniego at the institute.

Late in the book, we learn Dr. Samaniego isn’t really a psychiatrist, or at least not a good one—he doesn’t have the empathy to do the job. It’s possible none of his patients are actually ill. Dr. Samaniego doesn’t treat disturbed people. He treats people who disturb everybody else. The patient’s experience and everyone else’s experience of the patient are all the same to him. He wants people to be peaceful, tranquil, like a dog sleeping in the sun. Which turned out to be a good metaphor to have on hand when he discovered the physical location of the human soul, and figured out how to transplant it into other bodies. Like dogs. Dr. Samaniego’s rest cure involves literally “plunging into animality.”

And once you have the soul out of its body that opens up other solutions for “disturbance.” See, people are fungible. Interchangeable parts in a big machine. Dr. Samaniego can take people who doesn’t fit and move them to new bodies and new lives where they’ll fit better. He can’t make people well, but he can make people convenient. He’ll return Diana’s body to Lucio with a different, more compatible soul.

Everyone but Lucio is delighted with the new Diana. He notices she doesn’t remember things she should remember; he catches her going through photos and family trees to get up to speed on her own life. More importantly, she’s not herself. Only Lucio cares enough to notice, which means Lucio is beginning to present Dr. Samaniego with difficulties.

As James Sallis’ introduction to the NYRB Classics edition points out, all this feels like a gently comedic take on Invasion of the Body Snatchers. And as with Jack Finney’s novel you can read this as a political metaphor. Bioy Casares was an Argentine writer and published Asleep in the Sun in 1973, right before the beginning of the “Dirty War” in which the government disappeared thousands of people. At this point Argentina had been ruled by a military junta since 1966. It’s not hard to imagine why Bioy Casares might have chosen this moment to write a novel setting love for unique and irreplaceable, if troublesome, individuals up against an authority that sees them as machine parts to be swapped out if they throw the gears out of alignment. Or why it’s dangerous to be the person who notices, or cares.