This will take explaining. A few years back I wrote a series on the short stories, novellas, and novelettes nominated for both a Hugo and a Nebula award. The point, often missed, was to take them as a group and ask what might have appealed to genre fans. I got as far as 1973, then was derailed by Covid. The 1974 list had a whopping ten stories to pull together, and by the time I’d recovered enough executive function to manage it I’d lost the thread.

Now, though, I need a project to keep from wasting every evening doom scrolling. So here I am, returning to my years-old notes on 1974.

I found a surprisingly unified thematic narrative weaving in and out of these stories. But because this post is turning out very long, I’m splitting it in two (maybe three). This one will take us halfway; I’ll link the second part at the bottom of this post once it’s finished, which will take… a week? Two weeks? I dunno, man; these days my ability to write is capricious.

1974

The novels nominated twice in 1974 were Arthur C. Clarke’s Rendezvous With Rama, David Gerrold’s The Man Who Folded Himself, Poul Anderson’s The People of the Wind, and Robert A. Heinlein’s Time Enough for Love. Rendezvous With Rama won both the Hugo and the Nebula. I thought it was mediocre. It’s been ages since I read The Man Who Folded Himself but I recall it as a novel for readers who found Heinlein’s “All You Zombies” overly tame. I’ve never read Time Enough for Love and I’d never even heard of People of the Wind.

For calibration, other SFF-adjacent novels published in 1973 included J.G. Ballard’s Crash, William Goldman’s The Princess Bride, and Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow. In a pleasant surprise, Pynchon got a Nebula nomination.

These are the stories that made both the Hugo and Nebula shortlists:

- Michael Bishop, “Death and Designation Among the Asadi”: An ethnographer living among ostensibly uncivilized aliens goes bonkers. (Worlds of If, January-February 1973)

- Michael Bishop, “The White Otters of Childhood”: Thousands of years from now, the remnants of humanity are relegated to an island on an earth ruled by advanced posthumans and de-evolved morlocks. But the really relevant Wells story is The Island of Dr. Moreau. (The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, July 1973)

- Gardner Dozois, “Chains of the Sea”: The aliens have landed. One boy discovers they’re not here to talk to us. (Chains of the Sea)

- Harlan Ellison, “The Deathbird” (Won the Hugo for Best Novelette): Adam—you know the one—reincarnates to turn out the lights on a dying earth. (The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, March 1973)

- George R. R. Martin, “With Morning Comes Mistfall”: On an alien world, a scientist makes a discovery. Everyone feels mildly let down. (Analog, May 1973)

- Vonda N. McIntyre, “Wings”: On another alien world, a temple guardian takes in an injured youth. They don’t get along. (The Alien Condition)

- Vonda N. McIntyre, “Of Mist, and Grass, and Sand” (Won the Nebula for Best Novelette): A post-apocalyptic healer treating a patient from another culture loses her best snake. (Analog, October 1973)

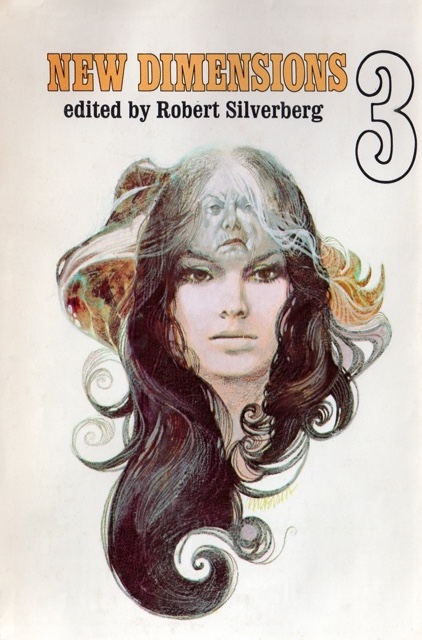

- James Tiptree, Jr., “The Girl Who Was Plugged In” (Won the Hugo for Best Novella): In a future where all advertising is product-placement on reality television, an outcast teenager remote-controls the body of a corporation’s perfect artificial celebrity. (New Dimensions 3)

- James Tiptree, Jr., “Love Is the Plan the Plan Is Death” (Won the Nebula for Best Short Story): An alien would like to have sex without dying afterwards, thanks. (The Alien Condition)

- Gene Wolfe, “The Death of Doctor Island” (Won the Nebula for Best Novella): A talking island provides dubious psychiatric care. (Universe 3)

Plugging In

In this batch of stories “The Girl Who Was Plugged In” is the biggest news. It’s aged alarmingly well, anticipating reality TV and the online micro-celebrities we call “influencers” whose job is to be seen consuming; product placement as a medium in itself. More significantly, “Girl” is an important precursor of what would become known as cyberpunk. The merging of body and machine, the mind as software. Crap consumerism. Mega-corporations routing around an impotent government. No virtual reality, but an engineered celebrity who’s only virtually real. A protagonist from society’s margins. Cyberpunk shares DNA with the hard-boiled detective story: The system arrayed against you is vast. Expect small victories, if any. Societal maintenance has been deferred too long; the streets are always and irredeemably mean. Against SF’s traditional instincts, technological advances go hand in hand with social entropy.

“Punk” as genre descriptor is a reference that’s shed its referent; these days it’s a suffix like -ing that turns words into genres instead of gerunds. (Solarpunk! Hopepunk! Steampunk, because who’s more punk than Charles Babbage?) But the original term took off because it suggested an attitude, for good (everybody loves when the street finds its own uses for things) and ill (“Cyberpunk” was coined in a short story by Bruce Bethke, who meant “punk” in the sense of “young troublemaker”). “The Girl Who Was Plugged In” speaks in punk prose: its voice is a disillusioned kid who sees the society his elders built as a thin rind over a rotten core, trying nihilism on for size—slangy, cynical, young but jaded. “Listen, Zombie.” “At the local bellevue the usual things are done by the usual team of clowns aided by a saintly mop-pusher.”

He’s telling the tale of Philadelphia Burke, an unglamorous kid plucked off the street to puppet a corporation’s perfect influencer. Her identity splits between the beautiful Delphi and the decaying P. Burke, neglected even by herself. What follows is a twisted fairy tale—the narrator references everything from Cinderella to the Golden Goose; Delphi is an “elf”—with a prince too dense to recognize his princess when she stands wired and emaciated before him.

One obvious reading of “Girl” casts Delphi as James Tiptree, Jr. and P. Burke as her secret identity, Alice Sheldon. At this point Tiptree’s identity was still secret, which wouldn’t last; her award nominations stirred curiosity and attendees of Worldcon, the yearly SF convention where the Hugos are awarded, spread wishful rumors Tiptree was attending in disguise. For Tiptree herself, “Girl” was about fame and celebrity obsession.

Most readers ignore its last-minute swerve. A “weasel-faced” young corporate technician, a nameless supporting character, blunders into a time machine and wakes up in the Nixon administration. He’s our narrator, addressing a present-day “Zombie,” from his perspective a literal dead man. Time travel drops into the denouement like a piano from a clear sky; it has nothing to do with anything to that point. So what’s up?

Here—and I’ll admit this is a tangent, but man will it be relevant as we go on—I’ll bring in John Rieder and his book Colonialism and the Emergence of Science Fiction. Rieder cites the anthropologist Johannes Fabian to argue one fundamental unexamined assumption of western anthropology in the 19th and 20th centuries was the idea cultures inhabit different points on an objective timeline of civilization. Encountering a “primitive” society was a kind of time travel. (To this day pop-science writers cite modern hunter-gatherer societies to support arguments about the ancient world.) “The way colonialism made space into time gave the globe a geography not just of climates and cultures but of stages of human development that could confront and evaluate one another,” writes Rieder.

So time travel can be a way to write about empire and colonialism. Poul Anderson’s Time Patrol, for instance, is openly and uncritically a cold war-era secret service meddling in a developing world. Kaliane Bradley’s The Ministry of Time, one of 2025’s Hugo nominees, is a more skeptical take on the metaphor. That’s not quite what’s happening in “Girl”—the metaphor isn’t colonialist. But it does signal an imbalance of power: the traveler from the future is, if not wiser, at least cannier.

Weasel Boy’s temporal status implies he’s a step above the 20th century natives, operating at a higher level. He needs an investment partner to take advantage of his future knowledge. Not to change anything; that’s not why he’s telling this story. His future’s teleology—inevitable, y’know? He just wants to set himself up with a comfortable place in it. And like P. Burke, he needs a front, a face. But we know implicitly no higher puppeteer will jerk his wires. P. Burke thought her story was a romance and her lover thought he was a pulp hero. The narrator knows better. Romantic heroism is giving way to cyberpunk cynicism.

The Truth About De-Evolution

Having introduced Rieder on SF and anthropology we turn to anthropological science fiction, a subgenre then in its heyday; Google’s Ngram search records the term becoming popular in the late 1960s and peaking around 1970.[1] It can feature literal anthropologists but is more about imagining different social structures, treating anthropology as material for speculation the way hard SF plays with physics. Writers associated with anthropological science fiction include Ursula K. Le Guin, Chad Oliver, and Michael Bishop, whose “Death and Designation Among the Asadi” is a critical dig at the old-fashioned anthropology Rieder examines.

This is Bishop’s first time on the Hugo and Nebula shortlists. He’d go on to have a long, successful career in SFF. These early stories already have strong prose and distinctive voices—worthy nominees, both—but also feel like he’s still figuring things out; at times he’ll make a move that’s too easy or too clichéd. Later he incorporated “Death and Designation Among the Asadi” into his novel Transfigurations.[2]

“Asadi” is presented as the edited field notes of ethnographer Egan Chaney, found-footage style. Like a found footage movie it gets more abstract and ambiguous as it goes on. Chaney is introduced reading Colin Turnbull’s 1961 ethnography The Forest People, the phrase “There are no more pygmies” looping through his head like a mantra. In this future “pygmy” society died after the Ituri forest was “poison[ed],” too polluted to inhabit. Now they’re dead or assimilated, a story. (If any part of Bishop’s story reads uncomfortably with fifty years of perspective, it’s this: it fridges a real-life civilization to motivate its protagonist.) Chaney daydreams himself into Turnbull’s book like a Tolkien fan wishing himself into the Shire: “Dreaming, I lived with the people of the Ituri.” (Bishop, to be clear, presents this romanticism as Chaney’s, not Turnbull’s.)

Chaney’s own subjects are the Asadi, maned humanoids who as far as humans can tell have no society, language, or instinct to cooperate, spending each day sitting passively in a clearing. Chaney hates the Asadi for reasons he has trouble articulating.

To cut a long story ruthlessly short the Asadi do have a language and are not always indifferent. They designate “chieftains” who live in the forest, occasionally returning with a noxious little bird creature Chaney recoils from. The chieftain brings the bodies of dead Asadi (we’ll discover he kills them himself) the crowd voraciously feast upon. Chaney follows a chieftain to a ruin full of evidence the Asadi once had an advanced technological society. He watches as the chieftain weaves a cocoon, sleeps, and emerges as—

—Well. Exactly what he was when he went in. The Asadi are determinedly static; in Chaney’s words they “institutionalize the processes of alienation,” to avoid acknowledging “where [their] next meal is coming from.” But people don’t do this to themselves, do they? No, it’s gotta be the bird, cause and symbol of the Asadis’ fallen state. Chaney kills it. The chieftain hatches another.

Again, from Rieder’s Colonialism and the Emergence of Science Fiction: early anthropologists saw societies they studied as more distant in time than space—they were different stages of human development, living examples of the past. They met other cultures not as equals but as exhibits, artifacts, mirrors—valuable for what they tell you about yourself.

Science fiction finds these attitudes hard to shake. Tech-focused as it is, it’s tempting for SF to rank civilizations by their technology. (The Asadi are so un-technological Chaney is stunned when the chieftain fashions straps to carry a body.) More to the point, SFnal aliens really, literally are there to tell us about ourselves. Stories are rhetorical devices, not descriptions of reality; everything in them exists to explore themes.

Rieder points out the temporal metaphor is also an excuse: if European colonists were conquering, assimilating, destroying indigenous societies, that was regrettable—but it wasn’t our fault, was it? Isn’t it natural for the past to fade away, replaced by the New? Chaney thinks of ethnography as preservation, documenting societies before they vanish. But he’s also reconciling humanity to their vanishing: alienating his subjects in the sense of making them other, living pieces of the past, stories for old books. He’s part of the institutions of alienation that get people comfortable offloading their environmental damage onto other people’s forests.

Chaney grows his hair and beard in imitation of a mane (Is this Chaney as in Lon Chaney Jr.?) and vanishes. “[E]ven though that throng is stupid,” he says, “even though it persists in its self-developed immunity to instruction,” he belongs with the Asadi.

Implicit in colonialist anthropology is a teleological view of history: civilization is a ladder leading up to utopia. By that logic the Asadi should represent a piece of our distant history they’ll grow out of in turn, growing closer to us. But the Asadi had a high-tech civilization. Humanity is their past. Which raises the possibility that history has no end point. Or, frighteningly, that history is teleological… but its inevitable end is not a utopian pinnacle, just a winding-down. At the top of the ladder is a chute.

That’s also worrying Moggadeet, arachnid narrator of “Love is the Plan, the Plan is Death.” This is our second story by Tiptree, who as a child was taken to the Ituri by her parents. (Her mother Mary Hastings Bradley memorialized the trips in Alice in Jungleland and Alice in Elephantland, making Tiptree perhaps the only SFF writer to also star in a children’s book series.) “Love” is one of two stories in this batch with no human characters. Both came from an anthology called The Alien Condition. (The other story, “Wings,” we’ll deal with later.)

Moggadeet comes to himself bounding through the hills, newly conscious in the warmth of Spring. His species straddles the line between people and animals: sapient in summer, in winter only as bright as your average arthropod. Moggadeet is suddenly an I, a being with a name, rediscovering language—“All my hums have words now. Another change!” He’s excited by language but struggles to master it, jamming words together experimentally into close-enough configurations for his thoughts. Not awkwardly; the rhythm of the prose bounds forwards, spills over itself like it’s trying to get ahead of something. We will learn Moggadeet hasn’t much time.

The problem is the Plan. Moggadeet’s people are ruled by instinct. Biological urges sort them into exaggerated stereotypes of patriarchal gender roles: large aggressive males fighting over small, nurturing females who, like praying mantises, eventually eat their mates. An older male introduces Moggadeet to new ideas. What could they accomplish if males didn’t kill each other? If females didn’t feed on their mates? If they found a way to stay conscious through the winters, held on to their free will and overruled their instincts? Like Katherine Hepburn says in The African Queen: “Nature, Mr. Allnut, is what we are put in this world to rise above.” Or if you recall your Wells: “Are we not men?”

It’s the old nature or nurture debate: are we the product of culture, or biology? The world’s worst people argue the side of biology, so it’s disconcerting that here Tiptree (as she will in “The Screwfly Solution”) plays pessimist: we don’t rule nature, nature rules us. This might have reflected her feelings about her own body; Julie Phillips, in James Tiptree Jr: The Double Life of Alice B. Sheldon, quotes an unfinished essay where Sheldon (writing privately, not as Tiptree) characterizes her reproductive system as a hostile parasitic machine. She was also capable of assuming the opposite: the cast of Up the Walls of the World incarnate in alien bodies and as pure data and retain their essential selves.

But look past the literal: Moggadeet’s struggle with instinct is a metaphor for the conflict between our conscience and intellect and our worst selves. Base desires, received ideas, thought-terminating clichés—actions and impulses that aren’t biologically determined, but are just easier than thinking through the right choice. In Freudian terms, your id vs. your superego. Your superego’s stronger than your id, right?

Maybe not. The problem is climate change. When it gets cold Moggadeet’s people revert to animal intelligence, and those winters are getting longer. Moggadeet schemes—maybe he and his mate can keep warm in a cave? But when she emerges from her cocoon, she eats Moggadeet anyway. He’s not really unhappy; he loves her, and anyway, it’s the Plan. But he’s afraid for the future. He begs his mate to tell the children “the winters grow.”

We don’t sense this will help. Summer’s too short to get your bearings. Moggadeet’s history is teleological, but its end point isn’t consciousness and complexity, just entropy. Civilization inevitably ends before it really gets started. We’re going backwards in time, leveling down.

The Doctor Says, “Solution is Simple.”

At this point it’s worth asking: what do SFF readers think of society? By which I mean America in 1974; the Hugos and Nebulas nominally honor any English-language SFF but all this year’s writers are Americans and the 1974 Worldcon was held in Washington D.C.

With ten stories to get through I can’t give every one the analysis it deserves. So although Gene Wolfe’s “The Death of Doctor Island” is, like all Wolfe’s work, complex and rich, it appears here mostly to answer the last paragraph’s question.

On a space station is an island, which is also a doctor—an AI psychiatrist that speaks through the wind, the monkeys, and the sea. (Joseph Weizenbaum’s Eliza had debuted less than ten years earlier; Weizenbaum was alarmed when some psychiatrists proposed a computer psychiatrist that could handle hundreds of patients an hour.) Its patients are Nicholas, a troubled teenager with a split corpus callosum; a violent loner named Ignacio; and the often catatonic Diane.

As they interact Ignacio seems to soften and Diane comes to life. In time Dr. Island announces Ignacio has been cured, but Nicholas discovers he’s murdered Diane. Dr. Island explains: Diane was incurably suicidal. Ignacio has an IQ of 210 and could make important contributions to society. So it sacrificed Diane to sate and neutralize Ignacio’s misogynist fantasies. Nicholas is enraged, but Dr. Island suppresses his personality in favor of Kenneth, the mute, tractable other side of Nicholas’ split brain. Dr. Island warns Kenneth he’ll have to fight to keep Nicholas from retaking control.

In 1967 a psychiatrist named David Cooper published a book called Psychiatry and Anti-psychiatry, giving a name to a movement of psychiatrists and philosophers who challenged the psychiatric establishment. Or not a movement, maybe, so much as a vibe; “anti-psychiatry” lumped together figures from R. D. Laing, who questioned medical models of mental illness, to Thomas Szasz, author of The Myth of Mental Illness (1972), who denied mental illness existed at all. (Cooper himself came to prefer the term “non-psychiatry.”) Broadly, though, anti-psychiatry would argue mental illness doesn’t have the same objective existence as malaria or a sprained ankle; sanity and insanity are defined against what society deems normal. Insane is a label given to people who don’t fit. At its most extreme anti-psychiatry casts psychiatrists as thought police: ACAB includes Counselor Troi.

You can see where the anti-psychiatrists were coming from: as late as 1974 the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders listed homosexuality as a pathology. On the other hand, clinical depression has existed in every society humans have devised, and hits privileged, successful citizens as often as nonconformists, so obviously something’s going on there.

Anti-psychiatry was largely left-wing—Cooper was Marxist, and blamed a lot on capitalism—and Wolfe was conservative. But there’s a lot here an anti-psychiatrist would recognize. Dr. Island decides who’s ill and who’s cured, or curable. Dr. Island decides the treatment. And “where there are so few individuals,” Dr. Island declares, “I must take the place of society.”

So, again: what kind of society is Dr. Island taking the place of? A violent one. Between the 1950s and the 1970s the U.S. homicide rate doubled; it would peak around 1980. The Vietnam war had just ended. In recent years Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy had been assassinated. Even young leftists, the peace-and-love people, our last hope for the future, were getting into terrorism. There were 130 air hijackings between 1968 and 1972. Bombings by groups like the Weathermen and Symbionese Liberation Army were a regular occurrence; the bombers rarely hurt anyone but themselves, but you never knew.

There were other problems. Rick Perlstein in The Invisible Bridge describes America in the early 1970s as having gone through a series of shocks that knocked its pride and self-image into the gutter. These included Vietnam, the first war we unambiguously lost; the 1973 oil crisis, our first hint that the energy we depended on could run out; and the lousiest economy the country had seen since the Great Depression. And then there was Watergate. The same issue of Analog in which “With Morning Comes Mistfall” appeared kicked off with an editorial by Ben Bova warning American presidents were, like Caesar, becoming god-kings. By 1974 the full scandal had broken. Nixon’s resignation came in August. But did that solve the underlying problem? Was the U.S. doomed to slide into autocracy?

Earth itself was dying. Climate change was on hardly anyone’s radar, but in the early days of the Environmental Protection Agency Americans were newly alarmed by pollution. Acid rain. Water so contaminated the Cuyahoga river sometimes caught fire. Smog that turned big cities a sickly yellow. (The fashion accessories catalogued in “The Girl Who Was Plugged In” include nose filters, a common worldbuilding detail in 1970s SF.) It couldn’t be long before the Earth, like the Ituri in “Death and Designation Among the Asadi,” was too poisoned to sustain human life.

In short, a society that killed its best and rewarded its worst, where the best-intentioned were either ineffectual or seduced by violence. Humanity faced problems too big to solve. America was markedly unsuited to solve anything anyway. What kind of society would sacrifice Diane to “cure” a killer with a cool IQ score? Maybe the kind SFF fandom was living in.

This is as good a moment as any to get George R. R. Martin’s “With Morning Comes Mistfall” out of the way. Today Martin is best known for a fantasy series about civilization falling apart as the winters grow, but in 1974 his focus was space opera written in polished post-New Wave prose but a Golden Age mode, the kind of Kipling-tinged planetary romance that unironically refers to humans as “Man.” This was Martin’s first award nomination, for one of his earliest stories; he wasn’t yet a full-time writer.

Wraithworld is a tourist planet known for omnipresent mists, mysterious ruins, and ghostly cryptids called wraiths said to kill the occasional visitor. Now a scientist named Dubowski plans to survey Wraithworld to prove or disprove the existence of the Wraiths. This pisses off local hotelier Sanders, who insists tourists visit Wraithworld not for the beautiful misty scenery but for the mystery and romance of the Wraiths. People need unanswered questions. Nevertheless, Dubrowski answers them: he recovers the bodies of the missing—a few accidents, one murder—and discovers the wraiths are a harmless “tribe of apes.” Science has conquered romance. Now Wraithworld is just, like, World.

In “Mistfall” human science and scholarship are destructive, spiritually enervating. Civilization is a clumsy steamroller. So it’s surprising it appeared in that bastion of conservative science-boosterism, Analog. Or maybe not; as Martin himself notes in his collection Dreamsongs, John Campbell had died a couple years earlier and new editor Ben Bova was anxious to stretch its horizons.

“Mistfall” follows the tradition of Campbellian SF in one way: it’s simple. Every other story on this list is (despite Harlan Ellison’s best efforts in “The Deathbird”) open to interpretation. They invite the reader in to poke around, collect multiple readings.[3] You can reread them and discover new themes. “With Morning Comes Mistfall” is a story with a capital-M Moral, very very anxious not to be misunderstood. It doesn’t even dignify Dubowski with a defensible argument. He’s an oafish clod and lousy debater, burbling vacuously about freeing benighted Wraithworld from superstition like a teenager who just discovered Richard Dawkins. The narrator describes him in the language of vivisection: he’s introduced as “a sharp voice” that “cut in”; he “planned his assault on Wraithworld”; he jabs a butter knife into the air to punctuate his conversation.

But we’ve seen shallow SF before. What sinks “Mistfall” is that for this story, with this message, shallowness is a structural problem. If you’re going to insist on the importance of mysteries and unanswered questions, refusing to leave any for the reader is just obtuse.

I also don’t buy the message. Wraithworld’s abandonment makes about as much sense to me as the idea tourists might stop visiting Yellowstone if they learned Bigfoot was just a bear standing on its hind legs. Unanswered questions are, anyway, a renewable resource. Get an underwhelming answer to one, ask another. “Mistfall” doesn’t even notice it’s dropped a big one: who built the ruins? The creatures Dubowski describes with that weirdly ambiguous phrase “tribe of apes,” as though both human and animal? What happened to them? What’s great about this mystery is that it has no definite answer. The Wraiths either exist or they don’t, but Wraithworlders could argue forever over how its civilization fell.

But in a year that already gave us Bishop’s Asadi and Tiptree’s Moggadeet, maybe lost civilizations are too common to wonder over. “Mistfall” thinks it’s possible for mysteries to run out, for humanity to reach the end of its imagination.

And, hard as it may be to believe, in the next part of this post things will get bleaker.

-

My inexpert, under-researched guess is that it was popularized by Leon Stover and Harry Harrison’s 1968 anthology Apeman, Spaceman. Stover was an anthropologist and SF. He also wrote an article for the journal Current Anthropology introducing SF to an audience of anthropologists which, like the stories covered here, was published in 1973. ↩

-

Whether in the same form, I don’t know—Bishop seems to have had a habit of revising his work for reprints, and I haven’t read Transfigurations. ↩

-

More and better readings than I’m offering here; you’ll have noticed I’m reading these stories to support a narrative. ↩

One thought on “Science Fiction Awards in 1974: Part 1”