1.

In science fiction circles Margaret St. Clair’s Sign of the Labrys is not much more than the answer to a trivia question: what book had the worst back cover blurb of all time? This one shouts “WOMEN ARE WRITING SCIENCE-FICTION!” in breathless all-caps, like it’s news. “Women,” we learn, “are closer to the primitive than men. They are conscious of the moon-pulls, the earth-tides. They possess a buried memory of humankind’s obscure and ancient past which can emerge to uniquely color and flavor a novel… Such a woman is Margaret St. Clair, author of this novel.” This copywriter seems either contemptuously sarcastic or very high.

Women in general and Margaret St. Clair in particular had been writing science fiction for a while by 1963, and St. Clair should be better remembered. I haven’t read her other novels—she’s maddeningly out of print—but her short stories feel like close Twilight Zone-ish cousins to Richard Matheson’s or Charles Beaumont’s, and at her best she’s just as good. (A couple of her stories were adapted for Night Gallery.) As for finding those stories… well, “The Man Who Sold Rope to the Gnoles” turns up all over, and you can find another story in The Future is Female, but as far as I know the only collection in print in the U.S. is The Hole in the Moon. It’s all worth tracking down.

I wanted to start with that recommendation because Sign of the Labrys is… uh, not a lost classic. But it’s also not worse than some books SF fans think are classics, and if the premise strikes you as interesting it’s a fine way to pass a couple of hours. And its flaws are at least interesting flaws. We’ll get into that.

2.

Anyway, that premise. This is a book where a yeast-based pandemic has depopulated the world and the survivors are afraid to get too close to each other. Which feels not so much “painfully on the nose” as “grabbed the nose and slammed it in a door.” Most people work menial, meaningless jobs—Sam Sewell, our narrator, moves boxes from one side of a warehouse to the other and back again, and no one cares whether he shows up on any given day. The only people with productive jobs are mass gravediggers and the mysterious dudes from the Federal Bureau of Yeast. Sam lives rent-free in a vast underground fallout shelter built by people who were extremely prepared for the wrong disaster, feeding himself on purple fungus and stockpiles of preserved pre-apocalypse food that never seems to spoil. Aside from the fungus, there isn’t much fresh food; too many species went extinct during the plagues.

One day Sam has a visit from a FBY man looking for a woman named Despoina. Sam has no idea who this is but the agent insists he ought to because Sam, like Desponia, is a witch.

Margaret St. Clair was a Wiccan and Sign of the Labrys is practically an advertisement for Wicca, which in this book is not just a neopagan religion but actually grants magical powers. (In this light the blurb’s blather about moon-pulls, earth-tides, and humankind’s obscure and ancient past vaguely makes sense.) Labrys is packed with stereotypically pagan accoutrements like athames and people substituting “Blessed Be” for “Hello,” and St. Clair cribbed ceremonies and other details from an influential mid-century occult writer named Gerald Gardner.

Sam learns Despoina may be in his own fallout shelter and spends most of the novel exploring its deeper levels. Sam’s descending into the underworld to retrieve occult knowlege. He’s also acting out a kind of story modern geek-culture types might find familiar. When the original Dungeons & Dragons came out in 1979, the creators included an “Appendix N” listing books that inspired them and right there, between Fred Saberhagen and J. R. R. Tolkien, was Margaret St. Clair with The Shadow People and Sign of the Labrys. Sam’s fallout shelter is a dungeon.

Even if you’ve never read a D&D manual you might recognize the “dungeon” concept from video games. A dungeon isn’t a literal dungeon (the name, one suspects, was chosen solely for the alliteration). It’s an enclosed space for the players’ characters to explore, filled with traps to avoid, puzzles to solve, and monsters to fight. A dungeon might be a cave, a castle, a tomb, or even (as in Myst) an island—the crucial thing isn’t that it’s literally enclosed, but that it’s self-contained. If people live in the dungeon they’re usually weirdos and rarely leave. Dungeons are challenges first and narratives second. Often they’re arbitrarily constructed and run on weird internal logic. (Why does that white house have a troll and a Flood Control Dam in the basement?) Peculiar though they are, “dungeons” are useful frameworks for exploration-based stories comfortable with a certain amount of absurdity. Star Trek and Doctor Who visit them a lot, enclosed spaces being great budget savers.

And dungeons are great if you want to mash random stuff together and watch it juxtapose. Dungeons are eccentric subworlds, strange terrariums whose isolation and artificiality are license to be whimsical. The levels of Sam’s fallout shelter are incongruous subcultures, unaware of each other—a laboratory complex where floods of lab rats carpet the floor, an artificial garden full of wealthy Eloi, a machine shop attended by a cookie-obsessed miniature-builder with a teleporter. A lot of this is never explained. At one point Sam meets a dog with human intelligence who shows him the gate to the next level. (Through charades, which Sam has to interpret: in true dungeon-crawling spirit, he’s solving puzzles to get around.) Sam never sees the dog again or learn what its deal is. You could look at this as half-assed worldbuilding, or as leaving the world open to interpretation. If you want to send a character on a metaphorical, surreal, symbolic journey, this kind of thing has potential.

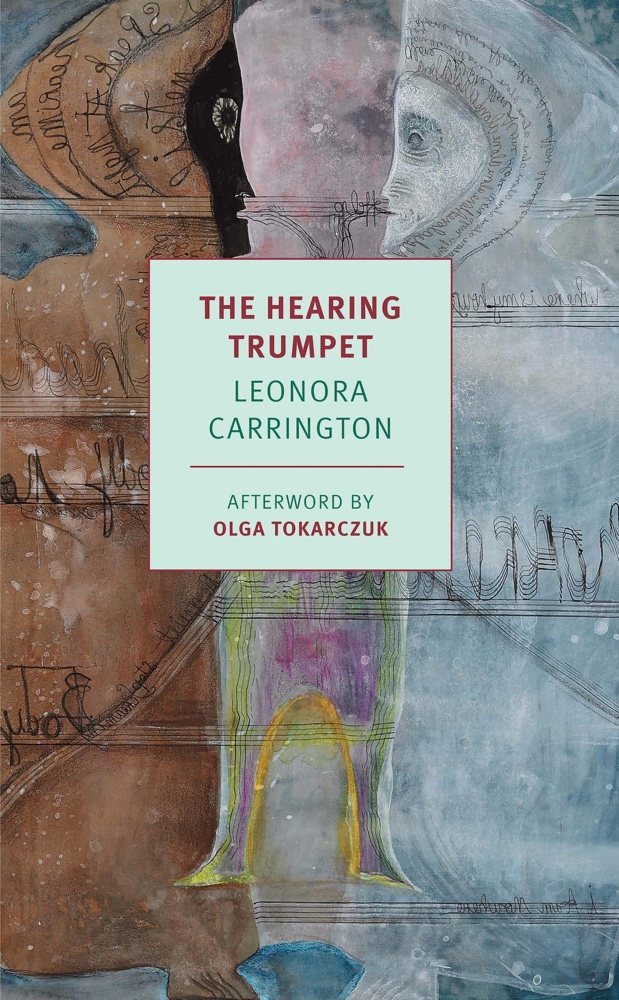

But if you want the reader to see the book as “open” and not “half-assed,” you have to live up to that potential. This is where Sign of the Labrys stumbles. On his journey Sam meets his long-lost half-sister Kyra who confirms that, yep, Sam’s a witch! Which means… well, mostly that he has X-Ray Vision, and can make people hallucinate. I read Sign of the Labrys soon after The Hearing Trumpet and, man, was that an unflattering comparison. Both books are surreal, symbolic spiritual journeys but The Hearing Trumpet ends in strange and numinous revelations. All Sam learns is that he’s a superhero. The spiritual journey got into a wrestling match with a pulp novel, and pulp won. This is in one sense banal but in another sense interesting enough to push me to review Sign of the Labrys. It’s a glaring example of a problem I’ve seen before—one of those glaring examples that brings a recurring pattern into clearer focus.

3.

There’s a common pattern in pop culture where a story is structured like a bildungsroman, but at the end of the story the protagonist isn’t a wiser or deeper or a more developed person, just more powerful. Or at least more assertive and confident. They haven’t grown as a person, just levelled up. Think Star Wars: Luke isn’t any more mature when he destroys the Death Star than he was at the beginning of the movie. Or superhero origin stories: often the point of these stories isn’t that their heroes develop. Instead, the heroes’ newfound powers let them express who they already were. (Captain America is brave and decent at the beginning of the movie; at the end he’s brave, decent, and strong.)

Now, in some cases this might be related to serialization. If you plan to keep using your protagonist, they can’t change too much too quickly. (Also, if they get really smart they might figure out how to stop getting themselves into adventures.) But Sign of the Labrys is a standalone novel. The problem here is that, for all that St. Clair is sharing her religion, Sign is a power fantasy and not a wisdom fantasy. (Again, the pulp narrative sucked everything into itself like a black hole.) Sam—and by extension anyone who identifies with him—doesn’t need to develop in any real way. He’s already great. He just needs to learn how to express his greatness.

Actually, Sam doesn’t learn so much as remember. Kyra spends some time preparing him to remember, but once he’s through his initiation Sam masters his Wiccan powers almost as soon as they’re introduced to him. It’s intuitive: he just knows how it all works. Sam has a buried secret identity, it turns out. Spoiler: he’s the Devil! Or “the person our persecutors called the devil,” according to Despoina. “They gave that name to the male counterpart of the high priestess, the other focus of power in the circle. You’re of the old blood, Sam.” Sam is one of those protagonists who are special because of what they are, not what they do.

Having learned this, it’s interesting to go back to the very beginning of the novel. Remember, this is first person narration: “There is a fungus that grows on the walls that they eat. It is a violet color, a dark reddish violet, and tastes fresh and sweet. People go into the clefts to pick it.” Notice the “they.” We soon learn Sam picks and eats this fungus, too—that’s how he knows how it tastes. But the fungus eaters are still “they.” From the first sentence, Sam’s narration is telling us he’s different from other people.

4.

At one point Sam (who’s been a witch for mere days but speaks with the confidence of an old hand) assures us “We Wicca are trained in scruple for life, if we do not possess it to begin with.” So it’s weird that when Sam thinks he’s accidentally killed someone[1] this is his reaction:

I sat down on the ground again by Cindy Ann’s body to think it over. Proximity to her didn’t bother me at all. It was like sitting down by an empty packing case, or a bundle of old clothes. I suppose it was because I didn’t have any feeling of moral responsibility for her death. And then, she hadn’t had much personality when she had been alive. Not much had been withdrawn.

Speaking as someone with not much personality, thanks, Sam. Of course there are such things as unreliable narrators, and unsympathetic protagonists, but Sam doesn’t appear to be either. There’s no sign we’re meant to find his thoughts troubling or absurd.

The real reason Sam isn’t bothered by Cindy Ann’s death is the same reason she doesn’t have much personality. Cindy Ann is a very minor character who only exists to deliver some exposition. Sam doesn’t care because the reader won’t.

Again, I’ve seen this before: stories that confuse characters’ importance to the story on a meta-level with their importance as people to the other characters. Sign of the Labrys doesn’t expect the readers to care about Cindy Ann’s death. We only knew her for a few pages. But Sam doesn’t care either. He only cares about people to the extent they’re structurally important as story-elements.

This problem gets really blatant when we learn Kyra’s history. Kyra, it turns out, released the plagues:

My face must have shown my shock, for Despoina said hurriedly, “Consider the situation, Sam. Have you forgotten? Nuclear war seemed absolutely inevitable. Nobody knew from day to day—from hour to hour—when it would begin. We lived in terror, terror which was sure to accomplish itself. Nobody even dared to hope for a quick death. “Kyra realized what had come into her hands. She acted. She took on her shoulders a terrible responsibility; she assumed a dreadful guilt. She knew that plagues are never universally fatal. She decided it was better that nine men out of ten should die, than that all men should.”

The only problem Despoina sees is that Kyra didn’t consult the boss witches first. Sam soon comes around to the idea that mass murder is okay, actually: “What a person Kyra was! Unhesitatingly she had taken on her young shoulders—she couldn’t have been over twenty at the time—the agony of a decision a god might have flinched from making. Mrs. Prometheus—I felt proud to be related to her.”

Now, to be scrupulously fair to Margaret St. Clair, who seems in all the others of her works I’ve read to be a normal empathetic writer, Sign of the Labrys came out the year after the Cuban Missile Crisis. Assuming a fast publication schedule parts of it might have been written during the Cuban Missile Crisis. If you wrote an SF novel during the gloomiest years of the Cold War you might be forgiven for building it around a giant half-joke of the “not ha-ha funny” kind. For decades people really believed humanity might be wiped out at any moment. We came close, more than once. I’m just old enough to remember the Reagan years and if you aren’t it can be a difficult headspace to get your own head around. Or maybe not. It wouldn’t surprise me if novels exist that toy with the idea of wiping out millions of people to avert the worst version of climate change.

Whatever. None of this, in any case, is compatible with sermons on “scruple for life.” You could look at this as a moral problem—that’s a popular critical lens these days, and not necessarily a bad one. But recently I read George Saunders’ new critical book and was struck by how he frames moral failures like sexism or racism as failures of craft—an authorial failture to fully and honestly imagine every character. And I think this is the best, most relevant way to look at Sign of the Labrys. It’s not just that the novel fails to empathize with the background characters. It fails to empathize with Sam. It doesn’t successfully imagine how someone with “scruple for life” would think, or depict him with emotional honesty.

Sign of the Labrys is trying to present Wicca as a positive, ethical system; presumably that was Margaret St. Clair’s experience with it. But the pulp narrative is divorced from any actual ethics and unlike those nameless extras it cannot be killed. Sam and Despoina defeat a fascist takeover by the FBY and find a strain of yeast that will heal humanity’s aversion to close contact. But they can’t fix the millions dead or the devastated ecosystem and the novel doesn’t grapple with that. Sam says, “We Wicca know how to be happy even in a bad world. But we are not content with a bad world.” But the world they’ve created isn’t good, just less crowded.

-

He thinks he unknowingly infected her with a deadly plague. Later the witches tell him he’s mistaken, but the real cause of death is never adequately explained. ↩