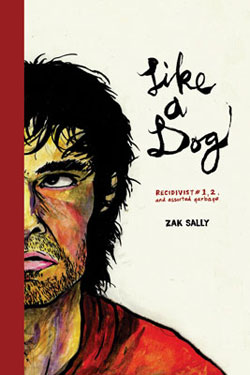

Zak Sally subtitled Like a Dog, a collection of his comics from the past decade-and-a-half, “Recidivist #1, 2, and Assorted Garbage.” This subtitle rushes past “too modest” to embrace “misleadingly self-deprecating.” As he explains in his notes, Sally’s not entirely happy with everything in this collection. It’s his figuring-things-out book, a record of how he hauled his work up from “competent” to a level where he could feel good about it. But he’s starting from competent.

None of the stories in this book are bad. Some are uncertain. These are the comics Sally created while he was figuring out what he wanted to do with comics. But the seeds of his style are already sprouting in the first pages of Recidivist #1. There’s thick, organic brushwork–some of Sally’s drawings look like they were grown. There’s a fascination with anatomy–between and within Sally’s stories are detailed anatomical studies which obviously paid off; in the torsos of the “Two Idiot Brothers” you can see every muscle. There are pools of black ink deep enough to lose things in.

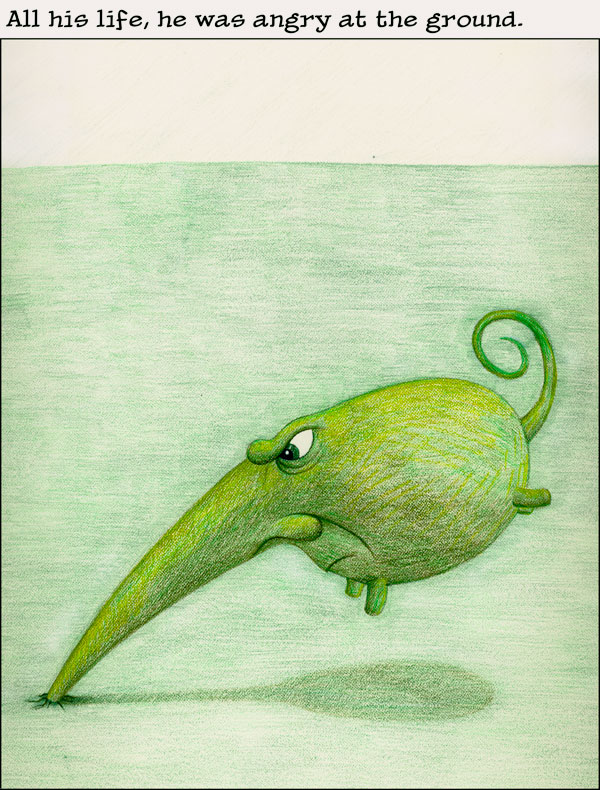

Sally often separates text and art. What I mean is that the text would be comprehensible by itself. The interaction between words and pictures are what comics are all about. Some comics achieve their effects by emphasizing one over the other. I think Sally is one of those cartoonists for whom words are the keystone. That can be a bad thing–newspaper and gag cartoonists in particular sometimes decorate words with redundant illustrations–but Sally’s pictures add extra layers of meaning and deepen the text. Sally’s text might mean something on its own, but his text plus his images mean something else, something more interesting.

An example of Sally’s experimentation with word and picture is “The End is Here, Now,” an autobiographical strip set on New Year’s Eve, 1999. It’s drawn in a three-tier grid. The panels are split horizontally. Above, straight text tells us what goes through Sally’s head: he’s amazed at the passage of time, he feels like something big should be happening. Below, comic panels with word balloons show us what he says and does: he wanders, has a drink, tries to climb a fence, and winds up at a party. The narration and the comic run in parallel, each independent until, in the next to last panel, Sally has a sudden and hazily understood realization…

…And, for the first time, the narration halts with a colon and jumps across to the word balloon. The narration and the pictures connect at the moment Sally’s internal monologue connects with the world. The last panel breaks the visual pattern set by the rest of the comic: an image of Sally looking up at the sky is framed by his thoughts at the top and the bottom.

For me, the most fascinating thing about Like a Dog was the afterward. Looking over my “Links to Things” posts, I notice I’ve frequently linked to articles about writing. Which is a little weird. My creative outlets are comics and drawings; I don’t have any ambition to write books, just reviews and blog posts. But I do read a lot. I like knowing how the books I read were written. (I often think people like me are the real audience for those “how to write a novel” books.) I like knowing how the comics I read were drawn. I can’t help feeling that Penguin Classics are superior to other books, not because they’re classics, but because they have introductions and footnotes.

In his afterward, Sally discusses the background of each strip in the collection. The strips collected in Like a Dog tell the story of how Sally learned and honed his craft. The story ends with Sally taking joy from the act of creation, but getting there was a hard trip. “My comics terrified me,” he writes. “I hated my comics, and I hated myself for making them; and, when I wasn’t doing that, I hated myself for not making them.”

Which is what really got my attention, because, man, I feel like that all the time.

Sally remembers worrying so hard about his craft that he was unable to start. I still get like that. I’ve found I have to be of two minds… first you have to get something down, without worrying about whether it’s any good; at that stage worrying will stop you cold. Then you have to switch modes and be hyper-critical, because inflicting half-assed failures of craft on your audience is disrespectful. You have to revise until the work is good enough to send out into the world. When you release the work you have to switch modes again, separate the finished work from your ego, because it’s in the hands of the audience and, good or not, some of the audience won’t like it, and you can’t take it personally. (Me, I only wish I had that problem–hardly anyone reacts to my work at all.)

Admittedly, that last paragraph was a detour; I’m trying to review Like a Dog, not my brain. And maybe this bloviation about craft is a little pretentious coming from, basically, a gag cartoonist. But it’s part of why I connected with this collection. It’s encouraging to learn that somebody this good has felt the same kind of self-doubt and worked his way out of it…. and that maybe it’s not so bad if, years after the fact, your early work embarrasses you. That just means you’ve learned something.